Battalion of detachments

A battalion of detachments is a term used to refer to battalion-sized units of the British Army formed from personnel drawn from several parent units. They were used to temporarily collect together detached companies or individual stragglers into more manageable-sized formations for logistics purposes or to provide additional fighting forces. Two longer-term battalions were raised by Arthur Wellesley in 1809 for service in the Peninsular War. These comprised stragglers left behind following the British withdrawal at Corunna and saw action in the Oporto and Talavera campaigns before they were disbanded and the men returned to their regiments. Though effective on the battlefield criticism was made of their discipline in camp and on the march and there was concern over the impact on manpower in their parent regiments. Other battalions of detachments were later formed in the field from British and foreign units in the peninsula and during the Walcheren Campaign. Three units of British line infantry were formed from depots in England in 1814 but saw no action before the hostilities ceased after the Treaty of Paris. Similar units were employed as late as the 1857 Indian Mutiny.

Early use

The British Army was organised into regiments, subdivided into battalions which were the usual unit of organisation and deployment on campaign. A battalion of detachments was a unit of battalion size formed from smaller sub-units such as companies or from individual soldiers that had become detached from their parent units. The use of such units was relatively rare in the line infantry but battalions of detachments had been formed of foot guard infantry during the American War of Independence and the 1798 Expedition to Ostend.[1] During the 1803 Battle of Assaye British general Arthur Wellesley (later known as the Duke of Wellington) formed the pickets – half companies detached from his seven line infantry battalions for guard duty – into a battalion of detachments which were deployed in battle under the command of the officer of the day.[2]

Napoleonic Wars

1st and 2nd battalions

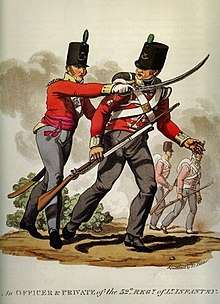

Arthur Wellesley[1]

Following the British retreat and the evacuation of Sir John Moore's army after the Battle of Corunna in January 1809 it was found that a sizeable number of men remained detached from the regiments within the British Army in Portugal. This included those convalescing in hospital in Lisbon, those who became separated during the retreat and other miscellaneous stragglers. As these men's regimental headquarters had been returned to England they were left without organization or logistical support. Brigadier-General Alan Cameron, commanding the British force at Oporto, gathered these men together under the auspices of a temporary battalion of detachments. This was primarily a means of bringing the men into the organizational structure of the army so that they could be supplied with rations and clothing to reduce the likelihood of them resorting to "every possible excess that could render the name of a British soldier odious to the nation". Later the unit would see active service in battle in a manner similar to more conventional battalions.[1]

Cameron ensured that where possible men were grouped together and led by officers from their own parent regiment. In the 1st battalion there were companies formed entirely of men from the 43rd Light Infantry, 52nd Light Infantry and the 95th Rifles – which proved invaluable to commanding general Arthur Wellesley, who was short of light infantry in Spain. The numbers of detached men and stragglers meant that soon a 2nd battalion was able to be formed, this was of slightly more homogenous composition than the 1st battalion.[1] On 6 May 1809 the 1st battalion comprised 27 officers and 803 men and the 2nd battalion 35 officers and 787 men. The 1st battalion formed part of William Stewart's brigade in Lord Paget's division and the 2nd battalion was in John Sontag's brigade in John Coape Sherbrooke's division.[3]

Both battalions fought well in the Oporto and Talavera campaigns.[1] The light infantry and rifles detachments were mentioned in dispatches three times for their actions at Oporto and the 1st battalion was commended by Wellesley on 31 July 1809 for gallantry and good conduct.[1][4] The 1st battalion was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel William Henry Bunbury of the 3rd Foot, who was awarded the Army Gold Medal in recognition of his and his units' exploits.[5]

Outside of the battlefield Wellesley acknowledged that he was disappointed by their conduct, his adjutant-general Charles Stewart claimed "they are the cause of great disorder – no esprit de corps for their interior economy among them, though they will fight. They are careless of all else, and their officers do not look to their temporary field officers and superiors under whom they are placed, as in an established regiment".[1] The British Army command at Horse Guards disliked Wellesley's retention of the men in the battalions claiming it resulted in a loss of discipline for the men and a loss of manpower for their parent regiments. British Army commander-in-chief David Dundas criticised the logistical arrangements for the units and their lack of discipline. He stated that the men's regiments were understrength as a result of the retention of the detached men and desired their return for foreign service, particularly for the proposed Walcheren Expedition and the battalions were disbanded following the victory at Talavera. The men were placed with their own regiments if they had a battalion in the Peninsula or else returned to their depots in Great Britain.[1]

Other units

A further unit, below battalion size, was formed of men separated from the two Kings German Legion light infantry battalions with Moore's army – this unit remained in service until 1811 when it was reabsorbed into the parent units which had returned to the peninsula.[1] A detachment battalion formed from part of the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards and 2nd Battalion 1st Foot Guards was sent to Cadiz in 1809. It fought at the Battle of Barrosa on 5 March 1811 where, either intentionally or as a result of confusion on the battlefield, it split into its two component units and fought separately. The unit was dissolved shortly after the battle, the Foot Guards being absorbed into the recently arrived 3rd battalion and the Coldstream Guards returning to England.[1] A detachment battalion was also used by Wellesley to garrison Gibraltar during the war.[6]

Dundas, despite his opposition to the concept when used by Wellesley in Spain, raised his own battalion of detachments (commonly known as the "Corps of Embodied Detachments") taken from the depot on the Isle of Wight. This numbered some 800 men from 17 different regiments which had been awaiting transport to join their units overseas. The corps deployed to the continent with British forces in July 1809 in the ill-fated Walcheren Campaign. When British troops were withdrawn later that year the corps was disbanded and the men returned to their regiments. The arrangement badly disrupted the supply of reinforcements to those regiments deployed overseas.[1]

In April 1814 General Henry Clinton formed a battalion of detachments at Tarragona, north-east Spain. It comprised men drawn from the British 67th Regiment as well as the foreign-raised Dillon's and Roll's Regiments.[7] A shortage of troops, exacerbated by the failure of a scheme to encourage militia soldiers to volunteer for duty abroad, led to the creation of further battalions of detachment in March 1814 by the commander-in-chief Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany. The manpower was drawn from units mustering at the regimental depots. The first battalion was intended to be formed from elements of the 5th, 63rd and 39th regiments of foot, the second from the 14th, 86th and 4th regiments and the final battalion from the 22nd, 9th and 19th regiments. However the numbers proved insufficient and further men had to be drawn from the 4th, 29th and 15th regiments. Three understrength battalions were formed before the 30 May Treaty of Paris ended hostilities between Britain and France. The Duke, unwilling to return to the commonplace 18th-century practice of moving men between regiments, disbanded the battalions and returned the men to their parent units.[1]

Later use

Battalions of detachments were also formed of British troops for the 1818 assault on Raigad Fort, India and the 1821 Beni Boo Alli Expedition to Eastern Arabia.[8][9] During the 1857 Indian Mutiny two battalions of detachments were formed to participate in the Relief of Lucknow. The first of these was formed from detachments of the three European regiments trapped in the siege and the second, somewhat weaker in number, may have been formed of native regiments.[10]

References

- Bamford, Andrew (2013). Sickness, Suffering, and the Sword: The British Regiment on Campaign, 1808–1815. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806189321.

- Biddulph, John (1899). The Nineteenth and their times. London: Murray. p. 138.

- "British Forces in Portugal, 6 May 1809" (PDF). Nafziger Orders Of Battle Collection. United States Army Combined Arms Center.

- Wellington, Arthur Wellesley Duke of (1815). The Principles of War, Exhibited in the Practice of the Camp: And as Developed in a Series of General Orders of the Duke of Wellington in the Late Campaigns on the Peninsula. W. Clowes.

- Cobbett's Political Register. W. Cobbett. 1810.

- Wellington, Arthur Wellesley Duke of (1872). Dispatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duc of Wellington, K.G.: May 1827 to August 1828. 4. Murray. p. 198.

- Wellington, Arthur Richard Wellesley Duke of (1861). Peninsula and South of France, 1813–1814. J. Murray.

- Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany. Wm. H. Allen & Company. 1818. p. 521.

- The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China, and Australia. Black, Parbury, & Allen. 1821. p. 367.

- Kaye, John; Malleson, George Bruce (2010). Kaye's and Malleson's History of the Indian Mutiny of 1857–8. Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 9781108023269.