Bathynerita naticoidea

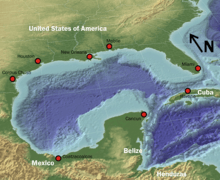

Bathynerita naticoidea is a species of small sea snail, a marine gastropod mollusc in the family Neritidae, the nerites. This species is endemic to underwater cold seeps (oil seeps and gas seeps) in the northern Gulf of Mexico[1] and in the Caribbean.[2]

| Bathynerita naticoidea | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. naticoidea |

| Binomial name | |

| Bathynerita naticoidea Clarke, 1989[1] | |

The possible placement of this species within the closely allied family Phenacolepadidae has been under discussion.[3]

Species from these habitats can be collected by manned submersibles[4] or by remotely operated underwater vehicles.

Distribution

This species lives in cold seeps in the northern Gulf of Mexico[1] and in the accretionary wedge of Barbados in the Caribbean[5] in the upper continental slope, in depths from 400 to 2100 m.[5]

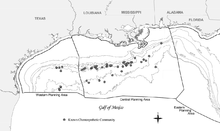

Examples of localities include:

Description

Bathynerita naticoidea - like other species in the family Neritidae - has a shell that can be closed with a calcareous operculum. The round shell is low-spired and smoothly sculptured. Its aperture has roughly a semicircular shape.

Genetics

Partial genetic sequences of mitochondrion of Bathynerita naticoidea were published in 1996[7] and in 2008:[8]

- 28S ribosomal RNA[7] - NCBI, NCBI

- cytochrome-c oxidase I (COI) gene[8] - NCBI

- 16S ribosomal RNA[8] - NCBI

Ecology

Habitat

Bathynerita naticoidea lives at deep-sea cold seeps where hydrocarbons (oil and methane) are leaking out of the seafloor. Bathynerita naticoidea lives around underwater hydrocarbon seeps, and it is the most numerous (dominant) gastropod species in its area.[5][9] This include oil seeps (= petroleum seeps)[9] and gas seeps (= methane seeps).[10] These seeps are also called cold seeps, in contrast to superheated hydrothermal vents.

Bathynerita naticoidea cannot move over the mud or on soft sediments,[11] and it usually lives on mussel beds of Bathymodiolus childressi.[12]

These snails normally live in saline water with salinity 30-50 ‰.[2] Bathynerita naticoidea is a euryhaline species.[5] They were also found near a brine pool seep in the Gulf of Mexico[2][5] and they can survive salinity as high as 85 ‰,[5] but they actively avoid brine with salinity over 60 ‰[2][5] and they usually move upward in natural conditions, where the concentration of salt is lower.[5] Bathynerita naticoidea has no osmoregulatory ability when the salinity is too high,[5] but it can survive high salinities, because it closes its operculum.[5]

Feeding habits

Bathynerita naticoidea feeds on periphyton of methanotrophic bacteria that grow on shells of mussels of Bathymodiolus childressi,[5][12] on decomposing periostracum of these mussels[12] and on byssal fibers of them.[12] It can also feed on detritus also on them.[5]

Bathynerita naticoidea can detect beds with mussel Bathymodiolus childressi, because it is attracted by a water altered by this species of mussel,[12] but the nature of the attractant was not discovered yet.[12]

Life cycle

Oogenesis and formation of yolk (vitellogenesis) of Bathynerita naticoidea was described by Eckelbarger & Young (1997).[4] This was the first ultrastructural description of formation of yolk in today's clade Neritimorpha.[4] This process is similar to other gastropods.[4]

Spermatogenesis of Bathynerita naticoidea was described by Hodgson et al. (1998).[10] Bathynerita naticoidea has sperm (eusperm) of introsperm type (about 90 µm long and filiform),[10] so it can be presumed, that the fertilisation of Bathynerita naticoidea is internal.[10]

Eggs are laid in round and white-rimmed egg capsules on various hard substrata:[2] the dorsal part of the shells of the mussel Bathymodiolus childressi.[13] They were found also on shells of mussel Tamu fisheri.[13] There are then scars from these egg capsules on these mussels.[13] Highest number of eggs are laid from December to February.[2] Eggs are 135-145 μm in diameter.[2] There are 25-180 eggs in one eggs capsule.[2] The length of the egg capsule ranges from 1.2 to 2.9 mm.[2]

During the development of the embryo, the egg capsule is changing color from creamy ivory color to dark purple color.[2] The cleavage is holoblastic spiral cleavage as in other gastropods.[2]

Veliger larvae are hatched from eggs after four months of development from May to early July.[2] Veliger is about 170 μm long (120-278 μm).[2] Veligers feed on plankton (planktotrophic)[2] and they are probably obligate planktotrophs. They can swim with ciliated foot and they are swimming probably for at least eight months.[2] Veliger have pigmented eyespots.[2] Maybe the same chemosensory mechanisms for detecting mussel beds can be used by its larvae.[12] Veliger in size 600-700 μm can undergo metamorphosis into a snail.[12] Only two protoconchs are known to be found in situ and they measured 630 μm and 615 μm in length.[2]

Interspecific relationships

There lives a fungal filamentous ascomycete (phylum Ascomycota) species as a commensal on the gills of Bathynerita naticoidea.[9] These fungi are externally attached to cells of gills.[9] When this discovery was published in 1999, it was the first such association between fungus and gastropod from underwater seep community.[9] The origin and function of this association is unknown.[9]

There are no known bacterial symbionts with Bathynerita naticoidea (1999).[9]

Other animals living in communities with Bathynerita naticoidea include:

- polychaete Methanoaricia dendrobranchiata from family Orbiniidae[5]

- mussels Bathymodiolus childressi from family Mytilidae[5]

References

- Clarke A. H. (1989). "New mollusks from undersea oil seep sites off Louisiana". Malacology Data Net 2(5-6): 122-134.

- Van Gaest A. L. (2006). "Ecology and early life history of Bathynerita naticoidea: evidence for long-distance larval dispersal of a cold seep gastropod". Thesis. Department of Biology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon. http://hdl.handle.net/1794/3717

- Kano Y., Chiba S. & Kase T. (2002). "Major adaptive radiation in neritopsine gastropods estimated from 28S rRNA sequences and fossil records". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 269: 2457-2465. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2178.

- Eckelbarger K. J. & Young C. M. (1997). "Ultrastructure of the ovary and oogenesis in the methane-seep mollusc, Bathynerita naticoidea (Gastropoda: Neritidae) from the Louisiana slope". Invertebrate Biology 116: 299-312. JSTOR.

- Van Gaest A. L., Young C. M., Young J. J., Helms A. R. & Arellano S. M. (). "Physiological and behavioral responses of Bathynerita naticoidea (Gastropoda: Neritidae) and Methanoaricia dendrobranchiata (Polychaeta: Orbiniidae) to hypersaline conditions at a brine pool cold seep. Marine Ecology 28(1): 199 - 207. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0485.2006.00147.x.

- Welch J. J. (2010). "The “Island Rule” and Deep-Sea Gastropods: Re-Examining the Evidence". PLoS ONE 5(1): e8776. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008776.

- McArthur A. G. (1996). "Molecular investigation of the evolutionary origins of hydrothermal vent gastropods". Thesis, University of Victoria, Canada.

- Frey M. A. & Vermeij G. J. (2008). "Molecular phylogenies and historical biogeography of a circumtropical group of gastropods (Genus: Nerita): implications for regional diversity patterns in the marine tropics". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 48(3): 1067-1086. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.05.009

- Zande J. M. (1999). "An Ascomycete Commensal on the Gills of Bathynerita naticoidea, the Dominant Gastropod at Gulf of Mexico Hydrocarbon Seeps". Invertebrate Biology 118(1): 57-62. JSTOR

- Hodgson A. N., Eckelbarger K. J. & Young C. M. (1998). "Sperm Morphology and Spermiogenesis in the Methane-Seep Mollusc Bathynerita naticoidea (Gastropoda: Neritacea) from the Louisiana Slope". Invertebrate Biology 117(3): 199-207. JSTOR.

- Van Gaest A. L. "Larval ecology of deep-sea snails. Archived 2010-11-28 at the Wayback Machine (slide 3)". accessed 1 May 2010.

- Dattagupta S., Martin J., Liao S., Carney R. S. & Fisher C. R. (2007). "Deep-sea hydrocarbon seep gastropod Bathynerita naticoidea responds to cues from the habitat-providing mussel Bathymodiolus childressi". Marine Ecology 28(1): 193-198. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0485.2006.00130.x

- Gustafson R. G., Turner R. D., Lutz R. A. & Vrijenhoek R. C. (1998). "A new genus and five new species of mussels (Bivalvia, Mytilidae) from deep-sea sulfide/hydrocarbon seeps in the Gulf of Mexico". Malacologia 40(1-2): 63-112. page 90 and page 96.

Further reading

- Carney R. S. (1993). caption 7: "Heterotrophic Megafauna of Chemosynthetic Seep Ecosystems". In: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Minerals Management Service. (1993). Chemosynthetic Ecosystems Studies Interim Report. Prepared by Geochemical and Environmental Research Group. U. S. Dept. of the Interior, Minerals Mgmt. Service, Gulf of Mexico OCS Regional Office, New Orleans, LA, 110 pp. PDF

- Zande J. M. & Carney R. S. (2001). "Population size structure and feeding biology of Bathynerita naticoidea Clarke 1989 (Gastropoda: Neritacea) from Gulf of Mexico hydrocarbon seeps". Gulf of Mexico Science 19(2): 107-118.