Lower Alsace

Lower Alsace[lower-alpha 1] (northern Alsace) was a landgraviate of the Holy Roman Empire held ex officio by the Bishop of Strasbourg.[1] Prior to is acquisition by the bishopric, it was held by the counts of Hüneburg.[2]

| Part of the series on |

| Alsace |

|---|

Rot un Wiss, traditional flag of Alsace |

|

|

|

|

|

Alsace in the European Union |

|

Related topics |

In 1174 Count Gottfried of Hüneburg was the landgrave when he got into a dispute with the Abbey of Neuburg near Hagenau.[3]

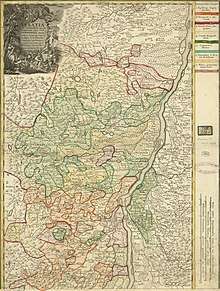

In the late Middle Ages the unity of Lower Alsace was lost. Strasbourg became an imperial city, owing allegiance to nobody save the emperor, and the great noble families gradually became extinct, their lands being inherited by families from across the Rhine. Lower Alsace thus had closer political connexions with the rest of Germany than did Upper Alsace. After the bishop, the greatest landholder was the Count of Hanau Lichtenberg. These nobles held vast estates outside of Alsace. The lesser nobility, confined in their holdings to Lower Alsace, but being immediate vassals of the emperor, were collectively known as the "Immediate Nobles of Lower Alsace".[4]

On 14 April 1646, the imperial ambassador Trauttmansdorff, during negotiations to end the Thirty Years' War, offered "Upper and Lower Alsace and the Sundgau, under the title of Landgraviate of Alsace" to the French.[1] There was no such territory, since Alsace was at the time divided into several jurisdictions held by competing powers. The Archduke Ferdinand Charles held the landgraviate of Upper Alsace, while a relative held the Landvogtei (bailiwick) of Hagenau with a protectorate over the Décapole (a league of ten imperial cities).[5]

Notes

- Known in French as Basse-Alsace, in German Unterelsaß and in Latin as Alsatia Inferior.

References

- Croxton 2013, pp. 225–26.

- Arnold 1991, pp. 131–32.

- Leyser 2003, p. 150.

- Hamilton 1928, p. 108.

- Beller 1970, p. 353.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Benjamin (1991). Princes and Territories in Medieval Germany. Cambridge University Press.

- Beller, E. A. (1970). "The Thirty Years War". In Cooper, J. P. (ed.). The New Cambridge Modern History, Volume 4: The Decline of Spain and the Thirty Years War, 1609–48/49. Cambridge University Press.

- Croxton, Derek (2013). Westphalia: The Last Christian Peace. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Hamilton, J. E. (1928). "Alsace and Louis XIV". History. 13: 107–17.

- Leyser, Karl (2003). Reuter, Timothy (ed.). Communications and Power in Medieval Europe: The Gregorian Revolution and Beyond. Palgrave MacMillan.

.svg.png)