Basil Brown

Basil John Wait Brown (22 January 1888 – 12 March 1977) was a self-taught archaeologist and astronomer who in 1939 discovered and excavated a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo in "one of the most important archaeological discoveries of all time".[1][2]

Basil John Wait Brown | |

|---|---|

| Born | 22 January 1888 Bucklesham, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 12 March 1977 (aged 89) Rickinghall, Suffolk, England |

| Occupation | Archaeologist, astronomer |

| Years active | 1932 to c. 1968 |

| Known for | Excavations at Sutton Hoo |

Although described as an amateur archaeologist, Brown's career as a paid excavation employee for a provincial museum spanned more than thirty years.

Early life

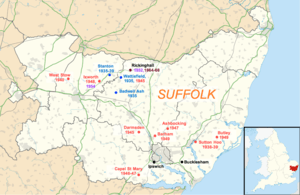

Basil Brown was born in 1888 in Bucklesham, east of Ipswich, to George Brown (1863-1932) and Charlotte Wait (ca. 1854-1931), daughter of John Wait of Great Barrington, Gloucestershire. His father was a farmer, wheelwright and agent for the Royal Insurance Company.[3][4]

When Basil was a few months old the Browns moved to Church Farm near Rickinghall, where his father begun work as a tenant farmer.[5] From the age of five Basil studied astronomical texts that he had inherited from his grandfather.[3][4] He later attended Rikinghall School and also received some private tutoring. From an early age he could be found digging up fields.[1] At 12 years old he left school to work on his father's farm.[5]

By attending evening classes, Brown earned a certificate in drawing in 1902. In 1907 he obtained diplomas with distinction for astronomy, geography and geology through studies with the Harmsworth Self-Educator correspondence college. Using text books and radio broadcasts Brown taught himself Latin and learnt to speak French fluently, while also acquiring some knowledge of Greek, German and Spanish.[3][4]

Although declared medically unfit for war service at the outbreak of World War I, Brown served as a volunteer in the Suffolk Royal Army Medical Corps from 16 October 1918 to 31 October 1919.[3][4]

On 27 June 1923 Brown married Dorothy May Oldfield (1897-1983), a domestic servant, and daughter of Robert John Oldfield, who worked as head carpenter on the Wramplingham estate.[4] Basil and May lived and worked on his father's farm even after George Brown had died, with May assuming responsibility for a dairy. They struggled to make a living, partly through Brown's preoccupation with astronomy, and partly due to how small the farm was.[3][5][4]

By 1934 the smallholding had become so unviable that Brown gave it up. He supplemented odd jobs by becoming a special police constable. In August 1935 he and May rented a cottage named Cambria in The Street, Rickinghall, where they lived until their deaths, having purchased it in the 1950s.[3][4][5]

Astronomical work

After the death of his mother, Brown and May lived for a short time in a school house, where he completed Astronomical Atlases, Maps and Charts: An Historical and General Guide, which he had started writing in 1928 and which was published in 1932.[4][5] Brown was nominated as a member of the British Astronomical Association in 1918,[6] and remained a member until financial straits forced him in 1934 to let his membership lapse. In 1924 he published articles on astronomical mapping and cataloguing in the independent publication The English Mechanic and World of Science, followed in 1932 by an article on Stephen Groombridge in the journal of the Astronomical Association.[3] Brown's Astronomical Atlases was sufficiently popular to be reprinted in 1968, with his publisher describing it as " 'filling an inexplicable gap in the literature' ".[1]

Early archeological career

In his spare time Brown continued to investigate the countryside in north Suffolk for Roman remains.[5] Intrigued by the alignment of ancient sites, he used a compass and measurements to uncover eight medieval buildings (one at Burgate, where his father had been born), identified Roman settlements, and traced ancient roads.[4]

His investigations of Roman industrial potteries led in 1934 to the discovery, excavation and successful removal to Ipswich Museum in 1935 of a Roman kiln at Wattisfield. In this way Brown got to know Guy Maynard, curator of the Museum (1920 to 1952) and H. A. Harris, secretary of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology. He applied to Maynard to work for the museum on a contractual basis.[1][3] His first contract with the Museum and the Suffolk Institute was for thirteen weeks of work in 1935 at Stuston and at Stanton Chare at £2 per week. At the latter site Brown discovered a Roman villa, leading to excavations that extended to three seasons of about thirty weeks in 1936-38[4] (until 1939, according to Maynard[7]). Archaeological work started to provide a semi-regular income for him, but at a lower wage of £1 10 shillings[8] per week, so that he had to continue working as an insurance agent and a special constable.[4]

Sutton Hoo excavations

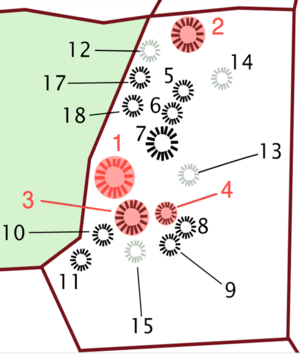

Landowner Edith May Pretty JP (1883-1942) were curious about the contents of about eighteen ancient mounds on her Sutton Hoo estate in southeast Suffolk. At a 1937 fete in nearby Woodbridge Pretty discussed the possibility of opening them with Vincent B. Redstone, member of several historical and archaeological societies. Redstone invited the curator of the Ipswich Corporation Museum, Guy Maynard, to a meeting with Pretty in July 1937, and Maynard offered the services of Brown as excavator.[9][10][11]

Sutton Hoo farm derives its name in part from the surrounding parish of Sutton and its village, where 77 households lived by 1086.[12] Sutton is a compound noun formed from the Old English 'sut' (south) and 'tun' (enclosed settlement or farm). The farm and its mounds have been recorded on maps since at least 1601, when John Norden included it in his survey of Sir Michael Stanhope's estates between Woodbridge and Aldeburgh.[13] The land was known variously as "Hows", "Hough", "Howe", and eventually "Hoo Farm" by the 19th century (ca. 1834-65).[14][15] "Hoo" likely means a "hill" - an elevated place shaped like a heel, from the Old English "hóh" or "hó" (similar to the German "hohe"), which is sometimes associated with a burial site.[16]

June–August 1938

Maynard released Brown from his employment by Ipswich Museum for June–August 1938, during which he was paid 30 shillings[8] a week by Pretty. Arriving on 20 June, Brown was lodged for the duration with Pretty's chauffeur. He brought along books spanning the Bronze Age to the Anglo-Saxon period and some excavation reports.[17] Given the proposed time limit of two weeks, Brown decided to copy the cross-trench digging methods used in 1934 excavations of Iron Age mounds at Warborough Hill in Norfolk, where similar time constraints had applied.[17][18][19]

With the help of Pretty's labourers, Brown excavated three mounds, discovering that they were burial sites showing signs of robbery during the medieval period.[4]

Brown first tackled what was later identified as Mound 3. Initially he found nothing, but evidence suggested a bowl-shaped area had been dug below. Following Maynard's recommendation Brown removed the soil and found a "grave deposit", off-set from the mound's center. Its location resulted perhaps from the shape of the mound distorting over time, or from the removal of some of its material. Early Saxon pottery was found, laying on a narrow 6-foot long wooden tray-like object - "a mere film of rotted wood fibers", plus an iron axe that Maynard later considered to be Viking (”Scandinavian"). Pretty decided to open other mounds, and two were chosen.[21][4]

In what was later known as Mound 2, Brown used the east–west compass-bearing of the excavated board found in Mound 3 to align a 6-foot wide trench. From outside the mound's perimeter he begun digging along the old ground surface towards the mound on 7 July.[21][17] A ship's rivet was discovered, along with Bronze Age pottery shards and a bead. On 11 July Brown found more ship's rivets, and asked Ipswich Museum to forward material on the Snape ship burial which was excavated in 1862–63. Pretty wrote to make an appointment for Brown with the curator of Aldeburgh Museum, where artifacts from the Snape excavation were housed. Maynard forwarded a drawing which arrived on 15 July and showed the pattern of the Snape boat's rivets. On 20 July Brown was driven to Aldeburgh by Pretty's chauffeur,[22] where he found the Sutton Hoo rivet to be very similar to those from Snape.[17][4][21][23] Back at Sutton Hoo, the shape of a boat with only one pointed end was uncovered. It seemed to have been cut in half, with one half possibly used as a cover over the other half. Evidence suggested that the site had been looted, as the upper half was missing. Signs of a cremation were found, along with a gold-plated shield boss and glass fragments.[21]

Brown excavated what was later called Mound 4, which he found to have been completely emptied of archaeological evidence by robbers.[21]

In August 1938 Brown went back to work for the Ipswich Museum, returning to the dig at Stanton Chare. Meanwhile, Maynard wrote to Manx Museum to find out more about ship burials.[4]

May–August 1939

At Maynard's request, due to his curiosity about the axe, Brown returned to the employment of Pretty for a second season. On 8 May 1939 he started to excavate Mound 1, the largest mound, assisted on Pretty's instructions by gardener John Jacobs and gamekeeper William Spooner.[21][20]

As before, Brown used the compass bearing uncovered in the end mound to start a narrow pilot trench outside the mound. On 11 May [20] he discovered iron rivets that were similar but bigger than those found in the 2nd mound, suggesting an even larger sailing vessel than the boat found earlier. Brown cycled to Ipswich to report the find to Maynard, who advised him to proceed with care in uncovering the impression of the ship and its rivets. Brown not only uncovered the impression left in the sandy soil by a 27-meter-long ship from the 7th century AD, but evidence of robbers who had stopped before they had reached the level of a burial deposit. Based on knowledge of ship burials in Norway, Brown and Maynard surmised that a roof had covered the burial chamber. Realizing the potential enormity of the find, Maynard recommended to Pretty that they involve the British Museum's Department of British Antiquities. Pretty demurred at the possible indefinite suspension of excavation that might result, but neither Brown or Maynard were willing to continue. Maynard thought that the boat was a cenotaph, as no evidence of a body was found, a position that he still retained by 1963.[21]

Charles Phillips, Fellow of Selwyn College, Cambridge, heard rumours about the dig during a visit to his university's Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Downing Street, Cambridge, and of the inquiries made of the Manx Museum about Viking ship burials. He arranged to meet with Maynard and they drove to Sutton Hoo from Ipswich on 6 June to visit the site. Phillips suggested that the British Museum and the Ancient Monuments Department of the Ministry of Works should be telephoned and informed.[4][25][26][20]

A meeting convened at Sutton Hoo by representatives of the British Museum, the Office of Works, Cambridge University, Ipswich Museum, and the Suffolk Institute three days later, gave Phillips control over excavations, starting in July. Brown was allowed to continue, and uncovered the burial chamber on 14 June, followed later by the ship's stern.[4] In 1940 Thomas Kendrick (Keeper, Department of British and Medieval Antiquities in the British Museum) suggested that the burial site was that of Raedwald of East Anglia.[27][28][2]

Having ensconced himself in the Bull Hotel at Woodbridge on 8 July, Phillips took charge of the excavations on 11 July.[20] Employed by the Office of Works, he convened a team that included W.F. Grimes, O.G.S. Crawford, Stuart and Peggy Piggot. On 21 July Peggy Piggot discovered the first signs of what later turned out to be 263 items.[29] Phillips and Maynard had differences of opinion, leading Phillips to exclude the Ipswich Museum. The press had come to learn of the significance of the find by 28 July.[4]

Brown continued to work on the site in accordance with his contract with Pretty, although excluded from excavating the burial chamber that he had located.[30]

On 14 August Brown testified at a treasure trove inquest which decided that the finds, transported to London for safekeeping due to the threat of war and concealed underground at Aldwych tube station, belonged to Pretty. Working with a farm labourer Brown took care to cover the excavated ship site with hessian and bracken.[4]

Brown returned again to his work at Stanton Chare in late 1939.[4]

After Sutton Hoo

During World War II Brown performed a few archaeological tasks for the Museum, but was principally engaged in civil defense work in Suffolk.[5] He served in the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes and in the Royal Observer Corps post at Micklewood Green.[3][31]

After the war Brown was again employed by the Museum, nominally as an 'attendant', but with archaeological, external duties. He joined the Ipswich and District Natural History Society and then the District Astronomical Society (1950-1957) when it broke away from its parent body.[3]

In 1952 he undertook excavations in Rickinghall that uncovered a long-since disappeared Lady Chapel at the Superior Church and a Norman font at the Inferior Church.[5]

Until the 1960s he steadily continued the systematic study of archaeological remains in Suffolk, cycling everywhere, and preparing an extremely copious (if sometimes indecipherable) record of information pertaining to it.[5]

In 1961 Brown retired from Ipswich Museum, but continued to conduct excavations at Broom Hills in Rickinghall between 1964 and 1968.[3] He uncovered evidence of a Neolithic presence, Roman occupation and the site of a Saxon nobleman's house.[5]

Death

During the Broom Hills excavations, Brown suffered either a stroke or a heart attack in 1965, which ended his active involvement in archeological digs. He died on 12 March 1977 of pneumonia at his home "Cambria" in Rickinghall[4] and was cremated at Ipswich crematorium on 17 March.[3]

Legacy and assessment

The regard in which Brown was held is evident from the efforts made by members of the Suffolk Institute to provide him with a pension. The Sutton Hoo scholar Rupert Bruce-Mitford ensured that Brown was awarded a civil-list pension of £250- in 1966.[4][32]

While he never published material on his archeological work as a sole author,[1] his meticulously kept notebooks, including photographs, plans and drawings are now kept by the Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service and Ipswich Records Office.[5] Out of this was developed the County Sites and Monuments Record of Suffolk, the basis of the record as it exists today. He encouraged groups of children to work on his sites, and introduced a whole generation of youngsters to the processes of archaeology and the fascination of what lay under the ploughed fields of the county.[5]

Brown's contributions to archaeology were recognized in 2009 by a plaque in Rickinghall Inferior Church. Yet he continues to be largely unacknowledged for his work at Sutton Hoo.[5] The plaque attests to his esteem among Suffolk archeologists, historians, and locals.[5]

The items found at Sutton Hoo as a result of his initial excavations continue to be studied through current scientific methods from time to time at the British Museum - most recently, yielding additional insights into the origin of bitumen found among the grave goods.[33]

The annual Basil Brown Memorial Lecture in his name was established by the Sutton Hoo Society, which supports research at the site of Brown's greatest discovery.[34]

A street in Rickinghall, the village where Brown lived, was named Basil Brown Close.[35]

Bibliography

- Brown, B. (1924). "Star Atlases and Charts". The English Mechanic and World of Science 119, Issue 3071: 4–5, 1 February.

- Brown, B. (1924). "The Star Catalogues". The English Mechanic and World of Science 120, issue 3105: 140, 26 September.

- Brown, B. (1932, 1968). Astronomical Atlases, Maps and Charts. Search Publishing Company, London, 1932. Reprinted by Dawson's of Pall Mall, 1968. ISBN 978-07-12901314.

- Brown, B. (1932). "Stephen Groombridge FRS (1755-1832)". Journal of the British Astronomical Association 42, no. 6: 212. Read by Frederick Addey to the BAA meeting of 30 March.

- Maynard, G., Brown, B., Spencer, H.E.P., Grimes, W.F., and Moore, I.E. (1935). "Reports on a Roman pottery making site at Foxledge Common, Wattisfield, Suffolk". Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology 22, Part 2: 178–197. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- Maynard, Guy; Brown, Basil (1936). "The Roman settlement at Stanton Chair (Chare) near Ixworth, Suffolk (PDF)". Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology 22, Part 3: 339–341. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- Brown, B.J.W., G. M. Knocker, N. Smedley, and S. E. West (1954). "Excavations at Grimstone End, Pakenham". Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology 26, Part 3: 189–207. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

In addition, Brown was mentioned 44 times in observation reports published in the Journal of the British Astronomical Association.[3]

References and notes

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1977). "Obituary: Basil Brown" (PDF). Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology. Ipswich. XXXIV (1): 71.

- "Edith Pretty's gift of Saxon gold in the British Museum". Express.co.uk. 30 March 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- Barton, Bill. "Basil John Wait Brown (1888-1977)". oasi.org.uk. Orwell Astronomical Society (Ipswich). Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- Plunkett, Steven J. "Life of the Day - Brown, Basil John Wait (1888-1977)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- Doig, Sarah (6 March 2017). "Basil Brown: The invisible archaeologist". Suffolk Magazine. Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- According to Plunkett, Brown joined the British Astronomical Association in July 1918, while the Orwell Astronomical Society records the date of his nomination as November 1918

- Maynard, Guy (1950). "Recent archaeological field work in Suffolk" (PDF). Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. 25, Part 2: 205–16. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- Before 1971, twenty shillings made a pound; so Brown's salary decreased from 40 shillings per week at Stanton to a regular salary of 30 shillings per week.

- "The Royal Burial Mounds at Sutton Hoo". National Trust, UK. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- Weaver, Michael (1999). "In the beginning..." (PDF). Saxon - The Newsletter of the Sutton Hoo Society. 30: 1–2. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- "Obituary: Mr Vincent Burrough Redstone" (PDF). Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archæology and Natural History. XXIV.1: 61. 1946. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- "Place: Sutton". Open Domesday. opendomesday.org. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Buisseret, David (2003). The Mapmakers' Quest: Depicting New Worlds in Renaissance Europe. Oxford, UK: OUP. p. 156. ISBN 9780191500909. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- "Sutton". Key to English place names. University of Nottingham. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- Serjeant, Ruth (1995). "Who was Mr Barritt? Where did he come from? Where did he go?" (PDF). Saxon - The Newsletter of the Sutton Hoo Society. 23: 4. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- Morris, Richard (1857). The Etymology of Local Names. Judd & Glas. pp. 49, 63. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Brown, Basil (1974). "Chapter 4: Basil Brown's diary of the excavations at Sutton Hoo in 1938--39". In Bruce Mitford, Rupert (ed.). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archeology - Sutton Hoo and other discoveries. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. pp. 141–169. ISBN 978-05-75017047.

- Carver, Martin O.H. (1998). Sutton Hoo - Burial ground of kings?. Philadelphia, Penn.: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812234558.

- Brown writes in his diary about excavation techniques employed by "Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society, vol. 25, pp. 408-28" - a reference to R.R. Clarke and H. Apling (1935)'s An Iron Age Tumulus on Warborough Hill, Stiffkey, Norfolk. See also Carver 1998, p. 186, note 5.)

- Carver, Martin (2004). "A Summary of entries in diaries of Basil Brown (1938 and 8 May-11 July 1939) and Charles Phillips (12 July- 25 Aug 1939), relating to Mound 1" (PDF). Vol. 2 of the Field Reports: Fieldwork Before 1983. pp. 29–31. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- Maynard, Guy. "'Sutton Hoo' 1938-39. Letter to Miss Allen, dated 1963". The Sutton Hoo Research Project, 1983-2001. Martin Carver, 2004. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- This version of events is from Brown's diary, which contradicts accounts (e.g. Weatherly's) that he stopped excavating completely before cycling some 15 miles to Aldeburgh museum.

- Weatherley, Terry (2014). "A closer look at the treasures of Sutton Hoo" (PDF). Annual Report, Lowestoft Archaeological & Local History Society. 45: 2. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- Hoppit, Rosemary (2001). "I have a little something that may be of interest to you" (PDF). Saxon - The Newsletter of the Sutton Hoo Society. 34: 1. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Ship burial in Suffolk". Times [London, England]. Infotrac Newsstand. 15 August 1939.

- Phillips, Charles W (1979). "`Sutton Hoo en pantoufles'. Account written by Phillips and given to M.O.H. Carver on 27 May 1983" (PDF). The Sutton Hoo Research Project 1983-2001 Martin Carver, 2004. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- "Two anniversaries and a centenary" (PDF). Saxon - Published by the Sutton Hoo Society. 59: 7. 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Kendrick, T.D. (1940). "The discoveries at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk". The Antiquaries Journal. 20 (1): 115. doi:10.1017/s0003581500045650. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Dixon, Anne Campbell (24 August 2002). "Raedwald's return". The Telegraph (UK). Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Preston, John (26 March 2014). "Sutton Hoo: A new home for Britain's Tutankhamun". The Telegraph (UK). Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Micklewood Green may refer to an older name for Botesdale Green (see reference in Peggy Healey, 1924—2012) .

- Russell, Steven (2 November 2011). "They gave their treasures to the nation: Sutton Hoo, Orford Ness and more". East Anglian Daily Times. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Burger, P; Stacey, R J; Bowden, S A; Hacke, M; Parnell, J (2016). "Identification, Geochemical Characterisation and Significance of Bitumen among the Grave Goods of the 7th Century Mound 1 Ship-Burial at Sutton Hoo (Suffolk, UK)". PLOS One. 11 (12): e0166276. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166276. PMC 5132401. PMID 27906999.

- "Sutton Hoo Society". suttonhoo.org. Sutton Hoo Society. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- "Babergh and Mid Suffolk District Councils - Property Address". baberghmidsuffolk.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

Further reading

The story of the Sutton Hoo excavation and Brown's part in it has been told in various ways:

- Barlow, Peppy (1993). The Sutton Hoo Mob. A play with music, written for the Eastern Angles Theatre Company, which toured in Suffolk in 1993 and again in 2005, based specifically on the central characters of the events.

- Brown, Basil (1974). "Basil Brown's diary of the excavations at Sutton Hoo in 1938—39". Chapter 4, in Rupert Bruce-Mitford, Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archeology - Sutton Hoo and other discoveries. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. pp. 141–169. ISBN 9780575017047.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert L.S. (1975). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial. Vol. 1, Excavations, background, the ship, dating and inventory. London: British Museum. ISBN 9780714113319.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert L.S. e.a. (1978). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial. Vol. 2, Arms, armour and regalia. London: British Museum. ISBN 9780714113357.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert L.S. e.a. (1983). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial. Vol. 3, Late Roman and Byzantine silver, hanging-bowls, drinking vessels, cauldrons and other containers, textiles, the lyre, pottery bottle and other items. London: British Museum. ISBN 9780714105307.

- Durrant, Chris J. (2004). Basil Brown—Astronomer, Archaeologist, Enigma. (np).

- Evans, Angela Care (2008, reprint). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial. London: British Museum. ISBN 9780714105758. Searching account of the excavation and discovery.

- Green, Charles (1963). Sutton Hoo: The Excavation of a Royal Ship-Burial. New York: Barnes & Novle.

- Markham, Robert A.D. (2002). Sutton Hoo through the Rear View Mirror. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Sutton Hoo Society. ISBN 9780954345303. An account of the discoveries that draws only upon verified evidence from contemporary records and sources.

- Phillips, Charles W. (1987). My Life in Archaeology. Gloucester: Alan Sutton, p. 70ff. ISBN 9780862993627.

- Plunkett, Steven J. "Life of the Day - Brown, Basil John Wait (1888-1977)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Preston, John (2016). The Dig. New York: Other Press. ISBN 9781590517802. A novel dramatising the Sutton Hoo excavations.