Bartolomeo Caporali

Bartolomeo (di Segnolo) Caporali (Perugia, c. 1420 – Perugia, c. 1503–1505) was an Italian painter and miniaturist in Perugia, Umbria during the early Renaissance period. His style was influenced by Umbrian artists Gozzoli and Boccati, two of his first mentors, and continued to evolve as younger Umbrian artists came onto the scene, such as Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, Perugino and Pinturicchio. Although primarily a painter, he is also known for executing missals, restoration work, gilding, armorials, banners and celebratory decorations, which speaks to his decorative, detail-oriented artistic style.[1] His most famous works include Madonna and Saints (1487) for the church of Santa Maria Maddalena at Castiglione del Lago, The Virgin and Child Between Two Praying Angels, and his Adoration of the Shepherds.

Personal life

Caporali was born in the town of Perugia, Italy in 1420. He was from a family of artists, including his brother, Giapeco Caporali, and son, Giovanni Battista Caporali.[1] His father was a highly trained soldier and fully armored cavalryman as a “man-at-arms”. Caporali married Brigida di Giovanni Cartolari before 1480 and together they had seven children: three daughters, Candida, Lucrezia, and Laura and four sons, Giovanni, who was also a painter, Ser Camillo, Giampaolo, and Eusebio. According to housing records, he lived in a house in the vicinity of San Martino in Perugia in 1456, which he co-owned with his brother Giapeco.[2]

In addition to being an artist, Caporali was also highly involved in the politics of Perugia. He was prior of his town, camerlingo to the Company of Illuminators, was elected captain of the people and held leadership positions in the Umbria Painters Guild multiple times throughout his career.[3] His opinion was highly valued in the art community, as he was frequently called upon to estimate the value of other artists’ works. He was known to have an extremely even emotional temperament, and in one instance is described as being “phlegmatic”.[4]

His death occurred between 1503 and October 8, 1505, since a document of that date describes his son, a canon of San Lorenzo, as Ser Camillus quondam Bartholomei Caporalis, or “of the late Bartolomeo Caporali”. The last found document that mentions Caporali alive dates from 1503.[3]

Style

Caporali had an artistic style that is best described as chameleon-esque, as he was masterful at absorbing the new techniques, skills and fashions from his contemporaries. Although Caporali's work was best known within Umbria, he constantly collaborated with provincial Renaissance painters in order to learn, network and develop his style.[5]

One attribute known about Carporali's work is his acute attention to detail. This can be seen in the particular detailing in his figure's clothes in order to give substance and differentiate between fabrics; his angels’ robes have a velvety thickness, and his Madonnas have complex double drapes painted onto her cloaks.[3] Additionally, his work is known for the gentle facial expressions of his subjects and the peculiar transparency of their facial skin tone. Strong hints of gold in the flesh, large infantile eyes with hard blackish lines under the upper lids, overlong fingers, and sensitive mouths drawn by long parallel brushstrokes are all details that define his work.[2]

As with most Renaissance painters, Caporali's style transformed throughout his career as he was introduced and influenced by various artists. This pattern often relied upon which artists traveled and worked in Umbria, as well as younger, more talented contemporaries from Perugia that he learned and borrowed from. These artists included Gozzoli, Boccati, Benozzo, Bonfigli, Perugino, Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, and Pintoricchio. In his last works in particular, Caporali began strictly producing work related to the impersonal mass of religious Umbrian paintings which were inspired by Pintoricchio. The quality of his work severely declined with age, to the point at which his hand is almost unrecognizable in his last paintings.[4]

Training and early works

Little is known about Caporali's training, however there are two men that undoubtedly influenced his artistic career. Many art historians claim that he studied under Benozzo Gozzoli, whose influences are seen in many of Caporali's earlier works.[3] However, according to official records, Gozzoli didn't travel to Umbria until Caporali was about 30 years old. Others claim Caporali to be the student of Giovanni Boccati, however there is the same chronological issue, as Boccati didn't live in Perugia until 1445. Therefore, it is not known who first introduced Caporali or his brother to the art of painting.[4] However, most art historians attribute the majority of Caporali's training to Gozzoli.

The earliest documentary record of Bartolomeo Caporali is his matriculation in the Guild of Painters at Perugia in the year 1442.[4] Additionally, in the late 15th century, an important local school of painting developed in Perugia, its principal exponents including Benedetto Bonfigli, Bartolomeo Caporali, Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, Bernadro Pinturicchio and later the great Perugino. Although he collaborated with all of these artists, Caporali worked particularly closely with Bonfigli during the beginning of their careers. In fact, modern art historians have trouble discerning between their early works due to their strong resemblances in technique, most likely because they were educated under like influences, if not the same master.[2]

Following their father's death in 1452, Bartolomeo and his brother renounced their inheritance and moved to Porta Eburnea.[2] It is here that the first record of Bartolomeo's work appears in 1454 when he paints a Maesta and a Pieta for the Palazzo dei Priori in the Udienza dei Calzolari. This commission resulted in his attaining the status of an independent and highly regarded master.[5] From this point forward Bartolomeo received many commissions and expanded his network by collaborating on projects with celebrated artists such as Giapeco, Boccati and Bonfigli. His willingness to collaborate as well as master new techniques and skills in order to reach broader markets speaks to his talent as a networker and businessman. However, most works of this early period in his career are not documented, and it is difficult to pinpoint with whom he collaborated with on the work that can be identified as his.[4]

Notable works

One of his first major works was The Virgin and Child Between Two Praying Angels. Made around 1450, this painting is on panel with tempura, oil and gold ground, and is in good condition. The linear drawing and complex treatment in the folds of the clothes call to Bonfigli's work, indicating that he and Caporali had a professional relationship far before their first known collaboration in 1467. Additionally, this work distinguishes itself because of the angels’ placement on an upper register, implying depth.[3]

By the second half of the 1460s, Bartolomeo seemed to have solidified his place as a master in Italy. This is due to the increased documentation and preservation of his works from this period in both Perugia and Rome. While continuing to make painted and gilded objects for the municipality of Perugia and the abbey of San Pietro in order to make a steady income, Bartolomeo also worked on his more famous commissions.[4]

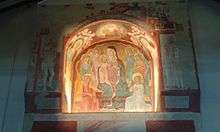

One such work is the Assumption of the Virgin in the Monastery of Santa Giuliana, Perugia. Completed in 1469, it is a monumental fresco with a light-toned composition distinguished with rich, elegant formal fabrics on the angels and the Virgin. It was very successful due to its “refined compositional archaisms in harmony with the older decorations of [the abbey]”,[5] and represents Caporali's ability to incorporate new techniques and styles successfully within older spaces.

The Caporali Missal is notable for several reasons. First, it was a decorated religious book containing the texts of mass, which is unlike most of the projects Bartolomeo worked on. Second, this missal in particular was a joint project with his brother, Giapeco. This missal was executed for the Franciscan convent of San Francesco, Montone near Perugia, an all-male convent that's remains still exist today. The missal itself was completed in 1469. Third, it survives complete with all of its four hundred folios in extremely good condition. The most prominent decoration of the missal is assigned to three full-page illuminations. Compared to other missals in this period, the Caporali missal was spectacularly decorative.[5]

His Virgin and Child with Six Angels appears to be the first picture painted in oils in this town, an honor which until discovered had been bestowed by Vasari to Perugino.[2]

His Adoration of the Shepherds (1477–79) represents his ability to exhibit learned skills from mentors and experiment in new mediums. The use of oil paint allowed him to pay greater attention to details through the use of new calligraphic tools, a skill he picked up from Bernardino Pintoricchio, who spent time in Bartolomeo's workshop a few years earlier.[5] Around this same time, Bartolomeo's brother, Giacomo, died in 1478. Subsequently, he was appointed to complete Giacomo's term of office as treasurer of the Guild of Miniaturists. During his time in this position, he painted a miniature representing the Annunciation in the choral books of the Monastery of San Pietro at Perugia.[3]

In the 1480s, Bartolomeo shifted towards the “gentle style” developed by Perugino on the walls of the Sistine Chapel and brought it to Perugia. One work that exemplifies this is his Madonna of the Windowsill, completed in 1484 and commissioned by the Alessandri family and Perugian jurists. His assistant at the time was Lattazino di Giovanni, who is thought to have worked alongside him during this period.[4]

Legacy and significance

Art historians differ on the degree of Caporali's influence to Renaissance painting. While Fliegel sees him as a major influencer on objectively greater Umbrian artists such as Fiorenzo di Lorenzo and Perugino, others find Caporali's contemporary Bonfigli to be his superior and assume the role of influencer in the Umbrian region during this period.[5] As Van Marle wrote, “When he did not have a more provincial artist to learn from, he had a tendency to descend to an almost provincial level.” [4]

However, few documented works of lesser-known Renaissance artists like Caporali's survive. As a result, there has been a tendency to grant attributions around the few recognizable artistic personalities of the period, when in fact they could belong to lesser-known masters such as Caporali. In the case of Caporali, one paper claims that the Giustizia triptych and the National Gallery altarpiece are likely his work and Sante di Apollonio, instead of Fiorenzo di Lorenzo's, to whom it is currently attributed. It would reveal the use of ideas from Paduan and Marchigian sources within pictorial structures that reference the work of Benozzo Gozzoli, combined with a determined effort to master the style of Perugino.[6] Its significance is that there may be more works of art during this period attributed to the greats that may belong to lesser-known Renaissance painters.

Major works

- Virgin and Child Between Two Praying Angels, 1450, private collection in France

- Enthroned Madonna and Child with Four Angels, 1450, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

- Annunciation, a triptych co-painted with Bonfigli (1467–1468), San Domenico (St. Dominic) Church, Perugia

- Maesta and a Pieta, ~1460, Palazzo dei Priori in the Udienza dei Calzolari

- Assumption of the Virgin, 1469

- Saint Francis of Assissi, Herculan, Luke and James the Greater, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

- Virgin, Child and Angels (1477-1479), National Gallery of Umbria, Perugia

- Virgin and Child With Six Angels, 1477–1479, National Gallery of Umbria

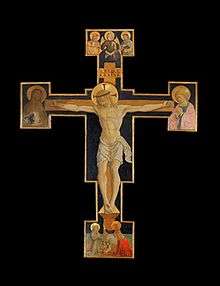

- Crucifix (1460-1470), San Michele Arcangelo

- The Angel of the Annunciation and The Virgin Annunciate (1460-1470), Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, Perugia

- Adoration of the Shepherds (1477–79)

- Gonfalon with the Madonna of Mercy and Saints (1482), Museo di San Francesco, Montone

- Madonna and Saints (1487) for the church of Santa Maria Maddalena at Castiglione del Lago

- The Virgin and Child Between Two Praying Angels

- Pietà (1486), cathédrale de Pérouse

- Sylvestrine Monk and a Lay Brother

- Caporali Missal, 1469, Perugia, Cleveland Museum of Art

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bartolomeo Caporali. |

- Fliegel, Stephen (2013.) The Caporali Missal. Cleveland, OH: The Cleveland Museum of Art and DelMonico Books.

- Bury, Michael. “Bartolomeo Caporali: A New Document and Its Implications.” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 132, no. 1048, 1990, pp. 469–475., www.jstor.org/stable/884276.

- P. Scarpellini. "Caporali." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 21 Feb. 2017

- Stanley Lothrop. “Bartolomeo Caporali.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, vol. 1, 1915, pp. 87–102.

- Van Marle, Raimond. "The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting: Volume XIV." (1933).

- Sarti, G (2000.) Early and Mannerist Paintings in Italy (1370–1570). Paris, France: G Sarti Antiques Ltd.

- Artfact,

- Notes

- P. Scarpellini. "Caporali." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 21 Feb. 2017

- Stanley Lothrop. “Bartolomeo Caporali.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, vol. 1, 1915, pp. 87–102.

- Sarti, G (2000.) Early and Mannerist Paintings in Italy (1370-1570). Paris, France: G Sarti Antiques Ltd.

- Van Marle, Raimond. "The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting: Volume XIV." (1933).

- Fliegel, Stephen (2013). The Caporali Missal. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art and DelMonico Books.

- Bury, Michael. “Bartolomeo Caporali: A New Document and Its Implications.” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 132, no. 1048, 1990, pp. 469–475., www.jstor.org/stable/884276.