Bardia Mural

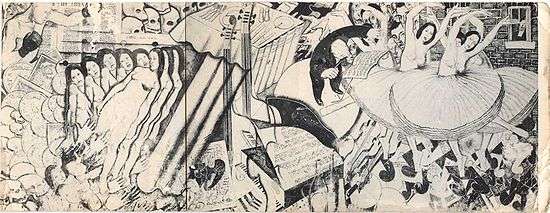

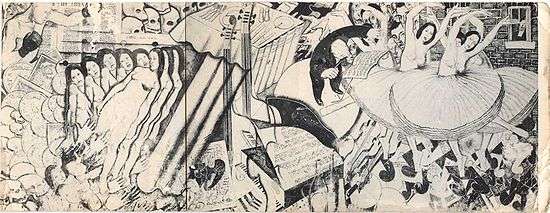

The Bardia Mural was created in a building on a clifftop overlooking the bay in Bardia, Libya, during World War II by John Frederick Brill just prior to his death at the age of 22.[1] It depicts a collage of images that range from the horrors of war shown by skulls to the memories of home, shown by wine, women and song.

| Bardia Mural | |

|---|---|

The mural in the 1950s | |

| Artist | John Frederick Brill |

| Year | 1942 |

| Type | Mural |

| Condition | Damaged by graffiti, and a large crack in the wall |

| Location | Bardia, Libya |

The mural still exists and can still be visited. It has, however, been defaced and its state has declined with a large crack in the wall on which it was created. Much of the lower part of the mural is lost.

As of April 2009, renovation work had been started by Italian artists who have filled the cracks and replaced broken plaster. Parts of the mural have been cleaned removing graffiti and restoring some of the 'blackness' of the paint.[2] A photograph of John Brill painting his mother can be seen here.[3]

Mural description

As can be seen from the photograph taken in the sixties, while the mural was still largely intact, it originally depicted Brill's memories of home, as well as the horrors of war. From left to right images of a boxer overlay a newspaper, beneath which money and piles of skulls, are followed by grasping hands reaching up to repeated and overlaid images of apparently naked women, whose facial features change subtely. Above these women can be seen the artists signature reference to the R.A.S.C. and the date of 21 4 42, with a further repetition of skulls above the signature. The image continues to unfold, on the other side of what appears to be a curtain separating the two sides of the mural, with pages of music, a grand piano and a table laid for a sumptious meal (many knives and forks), under which are fitted a number of books, which according to Lydia Pappas [4] represent the works of Charles Dickens From left to right: A Tale of Two Cities; Barnaby Rudge; David Copperfield; The Old Curiosity Shop and The Pickwick Papers. The image flows on to a conductor with more music, followed by a number of men's faces watching three ballet dancers, who are dancing on a floor of musical notes, the mural ends with the image of a face looking out of a window high up in a brick wall at the top right hand corner of the mural, which has variously been suggested to be the artist himself, or a relative back in "blighty" awaiting his return.

History

According to his mother,[5] Brill developed a passion for art at a young age. Having studied at the Royal Academy, he then went on to pass the entrance exam to study a 3-year diploma course at the Royal College of Art when the war broke out. His mother wrote, "His creed was that in order to become a great artist, he must suffer. Consequently he joined the Infantry, believing that to be the roughest and hardest of the services."[5] He fought in Europe and survived Dunkirk, after which his regiment was posted to the Middle East

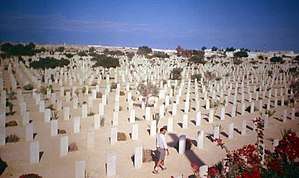

John Frederick Brill was a Private in the 5th Battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment.[1] He signed the mural on 21 April 1942,[6] a matter of weeks before his death. He died on 1 July 1942, the first day of the First Battle of El Alamein, aged 22.[1] He was buried at the El Alamein War Cemetery.[1]

Controversy

Early versions of the history of the Bardia Mural involved controversy. While it is commonly accepted that the mural was painted with paint, some versions stated that the material used to create the murals was Boot Black. There were also arguments over John's status when he painted the mural, indicating him as a prisoner of war or even under a death sentence. These three questions were referred to in a letter to the "Old Codgers" section of the Daily Mirror.

Brill's mother Eliza later wrote a letter, to answer the controversies, on 31 January 1966, having been shown a copy of the article about the mural which she knew her son had painted before his death. In the letter she stated that he originally painted a mural on each of the "four walls of the lad's canteen, which represented 'A Soldier's leave in Cairo'. This - I understand, afforded them much interest & amusement".[5] Following this the Officers asked Brill to create Murals in their Officer's Mess. According to John's mother the picture below represents one of these murals. The subjects being "The Pleasures of Avarice" and "The Pleasures of Art", and a third subject of "The Last Supper', "but this was never finished as his company was moved up the line." The Bardia Mural is likely to be one of these.[5] She goes on in her letter to state "I am thankful to say, that he was not under sentence of death, neither was he ever a prisoner."[5] She also states that the material used to create the various murals he painted during this period was paint, and not boot black; "paints were bought in Cairo, by the lads on leave and sent up by Convoy to Bardia. I understand that the costs were defrayed from the N.A.F.F.A. (sic) funds."[5] It is likely that she meant to refer to NAAFI funds.

Images of the mural

Uncropped photographs[7] taken by Donald Simmonds that show signs of wear and tear even then.

More photographs[8] that show graffiti.

2009 photographs[9] showing renovation in progress.

References

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission. "Last Resting Place". Retrieved 29 May 2006.

- Simmonds, Donald. "Restoration of Bardia Mural".

- Simmonds, Donald. "Bardiyah (Bardia) Mural by John Brill".

- Simmonds, Donald; Lydia Pappas. "Latest Updates". Retrieved 28 May 2006.

- Seccombe, John. "Letter to John Seccombe from Brill's Mother". Retrieved 30 May 2006.

- Simmonds, Donald. "Signature Close Up". Retrieved 29 May 2006.

- "1960s Don-simmonds.co.uk". Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2006.

- Don-simmonds.co.uk

- Don-simmonds.co.uk

External links

- FPRI.org, reference to the Bardia Mural by a U.S. visitor

- Yourmailinglistprovider.com, mention from another U.S. visitor

- Don-simmonds.co.uk, latest updates including renovation

- link to Google Map