Balikh River

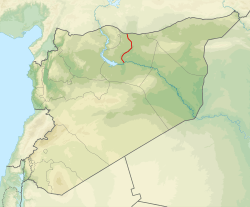

The Balikh River (Arabic: نهر البليخ) is a perennial river that originates in the spring of Ain al-Arous near Tell Abyad in Syria. It flows due south and joins the Euphrates at the modern city of Raqqa. The Balikh is the second largest tributary to the Euphrates in Syria, after the Khabur River. It is an important source of water and large parts have recently been subjected to canalization.

| Balikh Arabic: البليخ | |

|---|---|

| |

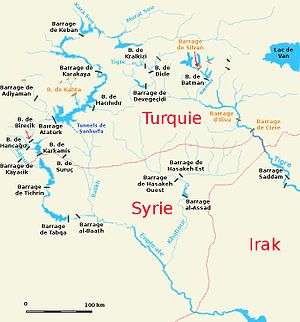

Map (in French) of the Syro–Turkish part of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, with the Balikh shown in the center left | |

| Location | |

| Country | Syria |

| Basin area | Turkey |

| Cities | Tell Abyad, Raqqa |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Ain al-Arous |

| • coordinates | 36°40′13″N 38°56′24″E |

| • elevation | 350 m (1,150 ft)approx. |

| Mouth | Euphrates |

• coordinates | 35°55′21″N 39°4′40″E |

• elevation | 250 m (820 ft)approx. |

| Length | 100 km (62 mi)approx. |

| Basin size | 14,400 km2 (5,600 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Ain al-Arous[1] |

| • average | 6 m3/s (210 cu ft/s) |

| • minimum | 5 m3/s (180 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 12 m3/s (420 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Jullab, Wadi al-Kheder |

| • right | Wadi Qaramogh |

| [2][3][4] | |

Geography

The primary source of the Balikh River is the karstic spring of 'Ayn al-'Arus, just south of the Syria–Turkey border. Additionally, the Balikh receives water from a number of periodical streams and wadis that drain the Harran Plain to the north, as well as the plains to the west and east of the river valley. These streams are the Jullab, the Wadi Qaramogh, and the Wadi al-Kheder.

A few kilometres south of 'Ayn al-'Arus, the Balikh is joined by the channel of the Jullab. This small river rises from springs north of Şanlıurfa, but already runs dry at Harran, before it can reach the Balikh. Numerous now dried-up wells in the old city of Harran suggest, however, that the water table may have been significantly higher in the past.[5]

The Wadi al-Kheder drains the plain to the east of the Balikh Valley, and is fed by the Wadi al-Burj and the Wadi al-Hamar, which in turn is fed by the Wadi Chuera. These wadis, as well as the Wadi Qaramogh, can transport considerable amounts of water after heavy rainfall, and large limestone blocks can be found in their lower courses.[6]

History

The Balikh river forms the heart of a rich cultural region. On both banks are numerous settlement mounds dating back in some cases to at least the Late Neolithic, the 6th millennium BCE. In the Bronze Age (3rd millennium BCE) ancient Tuttul (close to present-day Raqqa at the delta of the Balikh) and Tell Chuera in the north (in the Wadi Hamad close to the Balikh) were important cities. Over the millennia the region saw ongoing interaction between nomadic tribes and settled populations. One sometimes got the upper hand over the other.

In classical Antiquity the region was called Osrhoene with the capital at Edessa/Callirrhoe (ar-Ruha'.) Ar-Ruha' and another prominent ancient town of the Balikh valley, Harran (Roman Carrhae), figure in the Muslim and Jewish traditions respectively in the stories of Abraham and other Hebrew patriarchs (and matriarchs.) After the Islamic conquest in the 7th century CE the region was known by the name of an Arab tribe Diyar Mudar, the land of the Mudar. In 762 the Caliph al-Mansur built a garrison city at the junction of the Euphrates, Ar-Rafiqa, which merged with the Hellenistic city Kallinikos into the urban agglomeration Raqqa.

Archaeological research in the Balikh River basin

European travellers of the 19th century noted the presence of archaeological remains in the Balikh Valley, but the first investigations were not carried out until 1938, when the English archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan (husband of author Agatha Christie) spent six weeks investigating five archaeological sites dating from the seventh to the second millennium BCE.[7] In 1969 a French team directed by Jacques Cauvin started their investigations, his team exposed eight neolithic occupation levels in a limited sounding on the northern slope of the site.[8] Excavations at Tell Hammam al-Turkman were initiated under the direction of dr Maurits N. van Loon (1981-1986, University of Amsterdam).[9] As per 1988 the project was continued under the direction of dr Diederik J.W. Meijer ( 1988-2001, Leiden University). The site provided a well-stratified material culture that allowed analysis of the settlement history of the Balikh valley.[10] Later other excavations have complemented the reconstruction of a regional occupation history. One of the oldest sites, Tell Sabi Abyad, is currently being excavated under the leadership of Dutch archaeologist Peter Akkermans.

Incidentally, the Turkish archaeological site of Göbekli Tepe is located on a hill directly north of and overlooking the Harran Plains that feed the Balikh river system.

Excavated archaeological sites in the Balikh River basin

- Tell Aswad

- Tell Bi'a (near the confluence of the Balikh with the Euphrates)

- Tell Balabra (on the Wadi Qaramogh)

- Tell Chuera (Assyrian Harbe; on the Wadi Chuera)

- Tell Hammam et-Turkman

- Tell Jidle

- Tell Sabi Abyad

- Tell Sahlan

- Tell as-Saman

- Tell Zeidan (near Raqqa Syria)

References

- The discharge figures predate the introduction of large-scale irrigation works in the valley and may have changed significantly since then.

- Wirth, E. (1971). Syrien. Eine geographische Landeskunde. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. p. 110. ISBN 3-534-02864-3.

- Wilkinson, T.J. (1998). "Water and human settlement in the Balikh Valley, Syria: investigations from 1992-1995". Journal of Field Archaeology. Boston University. 25 (1): 63–87. doi:10.2307/530458. JSTOR 530458.

- "Volume I: Overview of present conditions and current use of the water in the marshlands area/Book 1: Water resources" (PDF). New Eden Master Plan for integrated water resources management in the marshlands areas. New Eden Group. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Lloyd, S.; Brice, W. (1951). "Harran". Anatolian Studies. British Institute at Ankara. 1: 77–111. doi:10.2307/3642359. JSTOR 3642359.

- Mulders, M.A. (1969). The arid soils of the Balikh Basin (syria).

- Mallowan, M.E.L. (1946). "Excavations in the Balih Valley, 1938". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 8: 111–159. doi:10.2307/4199529. JSTOR 4199529.

- Cauvin, Jacques (1970) Mission 1969 en Djezireh (Syrie), Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 67: 286-287 ; Cauvin Jacques (1972) Sondage à Tell Assouad (Djézireh, Syrie), in: Les Annales Archéologiques Arabes Syriennes 22: 85-88

- Van Loon M.N. (ed.) 1988, Hammam et-Turkman I. Report on the University of Amsterdam’s 1981-84 excavations in Syria, Uitgaven van het Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul, 63, Istanbul

- Akkermans, Peter M.M.G. (1990) Villages in the Steppe, Later Neolithic Settlement and Subsistence in the Balikh Valley, Northern Syria. Academisch Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Amsterdam; Bartl, Karin (1994) Frühislamische Besiedlung im Balih-Tal/NordSyrien, Berliner Beiträge zum Vorderen Orient, 15. Berlin; Curvers, Hans H. (1991) Bronze Age society in the Balikh Drainage (Syria), PhD-thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam; Gerritsen Fokke A. (1996) The Balikh Valley, Syria, in the Hellenistic and Roman-Parthian Age, unpublished MA Thesis, University of Amsterdam