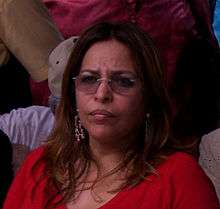

Balbina Herrera

Balbina Del Carmen Herrera Araúz (born c. 1955)[1] is a Panamanian politician and presidential candidate in the 2009 Panamanian general election. On May 3, 2009, she lost the race to the presidency of the Republic of Panama to center-right candidate Ricardo Martinelli.

Balbina Del Carmen Herrera Araúz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1955 |

| Nationality | Panamanian |

| Occupation | politician |

| Known for | 2009 presidential candidacy |

| Political party | Democratic Revolutionary Party |

| Children | three |

Career

She finished studies in the National Institute and the University of Panama, where she obtained her bachelor's degree with honours in Agronomy Engineering. She also holds post-graduate studies in education.

She served as Mayor of San Miguelito, congresswoman, and President of the National Assembly (1994-1995)[2] with the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD). When a male legislator once interrupted her to say that women should be at home with her children, she punched him and yelled, "Respect women!"[3]

As a National Assembly member in 1994, she opposed outgoing President Guillermo Endara's granting of temporary asylum to 10,000 Haitian boat people,[4] but supported his initiative to abolish the armed forces.[5] In 1996, Herrera supported President Ernesto Pérez Balladares's bill to grant amnesty to 950 former officials of military ruler Manuel Noriega, dismissing criticism of the bill as an attempt by fractured opposition parties to find a new common cause.[6] In the same year, she spoke out against an attempt to revive capital punishment after a wave of murders of bus and taxi drivers.[7]

Herrera was elected as President of the National Assembly in 1994, the first woman to hold the post.[3] She also served as chairwoman of the Parliamentary Trade Commission in 1998, calling on pharmaceutical companies to rein in rising prices or face government price controls.[8]

In December 2000, human remains were discovered at a Panamanian National Guard base, incorrectly believed to be those of Jesús Héctor Gallego Herrera, a priest murdered during the Omar Torrijos dictatorship. Moscoso appointed a truth commission to investigate the site and those at other bases.[9] The commission faced opposition from the PRD-controlled National Assembly, who slashed its funding, and from Herrera, who threatened to seek legal action against the president for its creation. The commission ultimately reported on 110 of the 148 cases it examined, concluding that the Noriega government had engaged in "torture [and] cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment", and recommending further exhumation and investigation.[10]

In 2001, Herrera led opposition to President Mireya Moscoso's appointment of former Interior Minister Winston Spadafora to the Supreme Court.[11] The following year, National Assembly member Carlos Afu, who was being expelled from the PRD for his vote in support of Spadafora's nomination, accused the party of taking bribes en masse under Herrera's leadership from the San Lorenzo consortium, a government contractor.[12]

During the presidency of Martin Torrijos (2004–09), Herrera served as Minister of Housing.[13]

2009 presidential election

Herrera served as the PRD candidate for President of Panama in the 2009 election. She won her party's primary on September 7, 2008, defeating Panama City Mayor Juan Carlos Navarro with a ten-point lead.[13] Herrera was endorsed by Ruben Blades, a popular salsa musician who had previously run for president and served as Torrijos' Minister of Tourism,[14] and was initially considered the favorite for the presidency.[15] If elected, she would have become Panama's second female president.[13]

However, Herrera was badly damaged in the election by her "reputation as a henchwoman of General Manuel Noriega"[14] and by the perception that she was a "Chavista", a supporter of leftist Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez.[1] Ricardo Martinelli, the candidate of the opposition coalition led by his Democratic Change party, was also helped by strong support from the business community.[14][15] On May 3, 2009, Martinelli won 60% of the vote to Herrera's 36%.[16] Former president Guillermo Endara also ran in the race, finishing a distant third.[1]

Personal life

Herrera has three children. She was divorced some time before 1999.[3]

References

- Sara Miller Llana (May 3, 2009). "Conservative supermarket tycoon wins Panama vote". Christian Science Monitor. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- PALABRAS LLANAS - 50 años de visión y Compromiso (1906-2006)

- Michelle Ray Ortiz (May 1, 1999). "Panama Could Have 1st Woman Leader". Associated Press – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- Tim Johnson (July 4, 1994). "Panama to help shelter Haitian refugees". Knight Ridder/Tribune News Service – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- "Panama". Caribbean Update. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . October 1, 1994. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- Silvio Hernandez (May 31, 1996). "Amnesty Endangers Governability". Inter Press Service – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- Silvio Hernandez (October 1, 1996). "Debate Over Death Penalty". Inter Press Service – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- Silvio Hernandez (November 13, 1998). "Backlash Against Spiraling Pharmaceutical Prices". Inter Press Service – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- Harding 2006, p. 131.

- "Truth Commission Delivers Its Final Report on Victims of the 1968-1988 Military Regime". NotiCen – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . May 2, 2002. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- "Legislators Warn that Battles between Administration & Assembly Could End in Chaos". NotiCen – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . November 15, 2001. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- "Legislator Who Revealed Alleged Bribery Scandal in Assembly is Expelled from His Party". NotiCen – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . April 11, 2002. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- Kathia Martinez (September 8, 2008). "Panama's ruling party picks woman for president". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- "Super 09; Panama's presidential election". The Economist. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . May 9, 2009. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- Anthony G. Craine. "Ricardo Martinelli". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- Lina Vega Abad (May 4, 2009). "Cifras, techos y realidades". La Prensa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

Bibliography

- Robert C. Harding (2006). The History of Panama. Greenwood Press. ISBN 031333322X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)