Badshah Begum

Badshah Begum (c. 1703 – 14 December 1789) was Empress consort of the Mughal Empire from 8 December 1721 to 6 April 1748 as the first wife and chief consort of the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah.[1] She is popularly known by her title Malika-uz-Zamani ("Queen of the Age") which was conferred upon her by her husband, immediately after their marriage.[2]

| Badshah Begum | |

|---|---|

| Shahzadi of the Mughal Empire | |

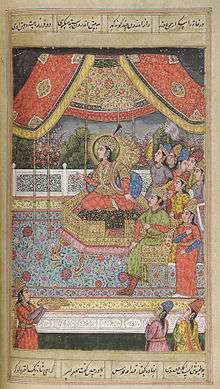

Badshah Begum seated on her throne. | |

| Padshah Begum | |

| Tenure | 1721-1789 |

| Predecessor | Zinat-un-Nissa |

| Successor | Zeenat Mahal |

| Born | c. 1703 |

| Died | 14 December 1789 (aged 85–86) Delhi, India |

| Burial | Tis Hazari Bagh, Delhi |

| Spouse | Muhammad Shah |

| Issue | Shahriyar Shah Bahadur |

| House | Timurid (by birth) |

| Father | Farrukhsiyar |

| Mother | Gauhar-un-Nissa Begum |

| Religion | Islam |

Badshah Begum was a first-cousin of her husband and was a Mughal princess by birth. She was the daughter of Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar and his first wife, Gauhar-un-Nissa Begum. She wielded major political influence in the Mughal court during her husband's reign and was his most influential wife. It was through her efforts that her step-son, Ahmad Shah Bahadur, was able to ascend the Mughal throne.[3]

Family and lineage

Badshah Begum was born c.1703, during the reign of her great-great-grandfather Aurangzeb.[4] She was the daughter of the later Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar[5][6] and his first wife, Gauhar-un-Nissa Begum. Farrukhsiyar was the second son of Prince Azim-ush-Shan[7] born to his wife Sahiba Niswan Begum.[8] Azim-ush-Shan was himself the second son of the seventh Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah I.[9]

Badshah Begum's mother, Gauhar-un-Nissa Begum (also known as Fakhr-un-Nissa Begum), was the daughter of Sadat Khan, a Mughal noble of Turkish origin,[10] who had been Mir Atish (head of artillery)[11] under Farrukhsiyar.[1] Being a Mughal princess, Badshah Begum was well educated, intelligent and had been instructed in the nuances of ruling and diplomacy.

Marriage

Muhammad Shah acceded to throne in 1719 and was a son of Prince Jahan Shah, the youngest son of Emperor Bahadur Shah I[12] and the younger half-brother of Emperor Farrukhsiyar's father, Prince Azim-ush-Shan. Badshah Begum was therefore, a first-cousin of her husband through her father's side. She married Muhammad Shah on 8 December 1721[13] in Delhi. The marriage was celebrated with great splendour. Accordingly, many of the officers presented lakhs of rupees and everyone received a dress of honour and jewels and increase of pay.[14] Upon her marriage, Badshah Begum was given the title of Malika-uz-Zamani ("Queen of the Age")[15] by which she is popularly known and further, the exalted title of Padshah Begum. Badshah Begum bore her husband his first son, Shahriyar Shah Bahadur, who died in his childhood. After that, she remained childless.[2]

Empress

Badshah Begum took an interest in several aspects of the state and governance and an active part in matters of importance. Being the Emperor's chief wife, she was the most influential among all of his wives and exercised her opinions on him. Muhammad Shah later developed a passion for a dancing girl, Udham Bai, a woman of no refinement, and made her a wife of his though Badshah Begum remained his favourite. This marriage resulted in the birth of a son, Ahmad Shah Bahadur. This son was brought up by the Empress as though he were her own son. She loved him greatly, and he grew up to ascend the throne due to her efforts.[1][16] Later, Badshah Begum also brought up Ahmad Shah's daughter, Muhtaram-un-Nisa.[17]

Badshah Begum commissioned elegant mansions in Jammu and in typical Mughal style, laid the foundations of pleasure gardens on the banks of the Tawi River.[18]

Dowager empress

In April 1748, Muhammad Shah died. Badshah Begum, concealing the news of his death, sent messages to her step-son Ahmad, who was in camp with Safdar Jang near Panipat to return to Delhi and claim the throne. On Safdar Jang's advice, he was enthroned at Panipat and returned to Delhi a few days later.[19] Badshah Begum was greatly respected by the court and the people as a Dowager empress, even after the Emperor's death.[16]

In February 1756, Badshah Begum's 16-year-old step-daughter, Princess Hazrat Begum, became so famous for her matchless beauty that the Mughal emperor Alamgir II, who was then about sixty, used undue pressures and threats to force Sahiba Mahal and the princess' guardian Badshah Begum, to give him Hazrat Begum's hand in marriage.[20] The princess preferred death over marrying an old wreck of sixty and Alamgir II did not succeed in marrying her.[20]

Role in Afghan invasion of Delhi

In April 1757, the Durrani king Ahmed Shah Abdali, after sacking the imperial capital of Delhi, desired to marry Badshah Begum's 16-year-old step-daughter, Princess Hazrat Begum.[21] Badshah Begum again resisted handing over her tender charge to a fierce Afghan of grandfatherly age but Ahmad Shah forcibly wedded Hazrat Begum on 5 April 1757 in Delhi.[22] After their wedding celebrations, Ahmad Shah took his young wife back to his native place of Afghanistan. The weeping bride was accompanied by Badshah Begum, her mother Sahiba Mahal, and a few other ladies of note from the imperial harem.[22]

During the Afghan occupation of Delhi, which lasted for two months and a half from 18 July to 2 October 1788, hell was let loose on Ahmad Shah Bahadur and the imperial family. He was deposed on 30 July 1788 and blinded ten days later. Ghulam Qadir took out Prince Bidar Bakht, son of Ahmad Shah, the ex-emperor from the imperial prison and made him the new puppet emperor with the title of Jahan Shah; he is said to have received 12 lakhs of rupees from Badshah Begum to wreak her vengeance against Shah Alam II, whose father Alamgir II had secured the throne by deposing and blinding Ahmad Shah.[23]

Death

Badshah Begum died in 1789 in Delhi and was buried in the Tis Hazari Bagh (Garden of Thirty Thousand) there. The garden had been commissioned by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan during his reign. Emperor Aurangzeb's daughter, Princess Zeenat-un-Nissa, was also buried in the Tis Hazari Bagh upon her death in 1721.[24]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Badshah Begum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1997). Fall of the Mughal Empire (4th ed.). Hyderabad: Orient Longman. p. 169. ISBN 9788125011491.

- Malik, Zahir Uddin (1977). The reign of Muhammad Shah, 1719-1748. London: Asia Pub. House. p. 407. ISBN 9780210405987.

- "Journal and Proceedings". Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal. 1907: 16, 360. Retrieved 15 September 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The American Society of Genealogists, The Genealogist, Vol. 11-12 (1997), p. 212

- Singh, ed. by Nagendra Kr. (2001). Encyclopaedia of Muslim Biography : India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. New Delhi: A. P. H. Publishing Corp. p. 455. ISBN 9788176482332.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Saha, B.P. (1992). Princesses, begams and concubines. New Delhi: Tarang Paperbacks. p. 32. ISBN 9780706963915.

- Robinson, Annemarie Schimmel ; translated by Corinne Attwood ; edited by Burzine K. Waghmar ; with a foreword by Francis (2005). The empire of the Great Mughals : history, art and culture (Revised ed.). Lahore: Sang-E-Meel Pub. p. 58. ISBN 1861891857.

- Cheema, G. S. (2002). The forgotten mughals : a history of the later emperors of the House of Babar ; (1707 - 1857). New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distr. p. 179. ISBN 8173044163.

- Richards, J.F. (1995). Mughal empire (Transferred to digital print. ed.). Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press. p. 260. ISBN 9780521566032.

- University, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, Aligarh Muslim (1972). Medieval India : a miscellany. London: Asia Pub. House. p. 252. ISBN 9780210223932.

- Singh, U.B. (1998). Administrative system in India : Vedic age to 1947. New Delhi: APH Pub. Co. p. 111. ISBN 9788170249283.

- Mehta, J. L. (2005). Advanced study in the history of modern India, 1707-1813. Slough: New Dawn Press, Inc. p. 24. ISBN 9781932705546.

- Awrangābādī, Shāhnavāz Khān; Prashad, Baini; Shāhnavāz, ʻAbd al-Ḥayy ibn (1979). The Maāthir-ul-umarā: being biographies of the Muḥammadan and Hindu officers of the Timurid sovereigns of India from 1500 to about 1780 A.D. Janaki Prakashan. p. 652.

- Singh, ed. by Nagendra Kr. (2001). Encyclopaedia of Muslim Biography : India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. New Delhi: A. P. H. Publishing Corp. p. 10. ISBN 9788176482356.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Malik, Zahir Uddin (1977). The reign of Muhammad Shah, 1719-1748. London: Asia Pub. House. p. 407. ISBN 9780210405987.

- Latif, Bilkees I. (2010). Forgotten. Penguin Books. p. 49. ISBN 9780143064541.

- Singh, ed. by Nagendra Kr. (2001). Encyclopaedia of Muslim Biography : India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. New Delhi: A. P. H. Publishing Corp. p. 86. ISBN 9788176482349.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Rai, Mridu (2004). Hindu rulers, Muslim subjects : Islam, rights and the history of Kashmir ([Nachdr.]. ed.). London: Hurst. p. 95. ISBN 9781850656616.

- Edwards, Michael (1960). The Orchid House: Splendours and Miseries of the Kingdom of Oudh, 1827-1857. Cassell. p. 7.

- Aḥmad, ʻAzīz; Israel, Milton (1983). Islamic society and culture: essays in honour of Professor Aziz Ahmad. Manohar. p. 146.

- A Comprehensive History of India: 1712-1772. Orient Longmans. 1978.

- Sarkar, Sir Jadunath (1971). 1754-1771 (Panipat). 3d ed. 1966, 1971 printing. Orient Longman. p. 89.

- Mehta, J. L. (2005). Advanced study in the history of modern India, 1707-1813. Slough: New Dawn Press, Inc. p. 595. ISBN 9781932705546.

- Blake, Stephen P. (2002). Shahjahanabad : the sovereign city in Mughal India, 1639-1739. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780521522991.