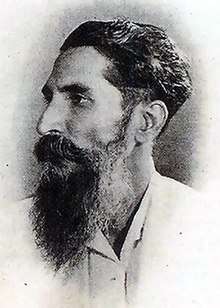

Baburao Painter

Baburao Painter (1890–1954) was an Indian film director.[1]

Baburao Painter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Baburao Krishnarao Mestry June 3, 1890 Kolhapur, British India |

| Died | January 16, 1954 (aged 63) Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India |

| Occupation | Director, painter, sculptor |

Life

He was born Baburao Krishnarao Mestry in 1890 in Kolhapur. He taught himself to paint and derives its name "Painter". (hence the name) and sculpt in academic art school style. He and his artist cousin Anandrao Painter between 1910 and 1916 were the leading painters of stage backdrops in Western India doing several famous curtains for Sangeet Natak troupes and also for Gujarati Parsi theatres. They became avid filmgoers following Raja Harishchandra.

Baburao and his cousin Anandarao bought a movie projector from the Mumbai flea market and proceeded to exhibit films, studying the art of movies all the while. Anandarao was busy with assembling a camera for their maiden venture, and his untimely death at this juncture compelled Baburao to go it alone

They turned to cinema first as exhibitors while trying to assemble their own camera. Anandrao however died in 1916 and Painter and his main disciple V.G. Damle eventually put together a working camera in 1918.

Film career

Baburao was one of the leading stage painter for theatres in Western India during the period of 1910 and 1916. He was also a film enthusiast and founded Maharashtra Film Company in 1919. To enable this Baburao borrowed money from Tanibai Kagolkar, a long-time admirer. Movie acting, especially tamasha's were looked down upon in conservative societies like Kolhapur so the studio itself was a living quarter for quite a few including leading ladies – Gulab Bai (renamed Kamaladevi) and Anusuya Bai (renamed Sushiladevi). Painter got onboard his old colleagues including Damle and S. Fatehlal and later on V. Shantaram, trio who later on left him to set up their own studio called Prabhat Film Company.

Baburao's first feature film was Sairandri (1920), which got heavily censored for its graphic depiction of slaying of Keechak by Bhima. However the movie itself got positive critics and commercial acclaim spurring Painter on to take on more ambitious projects. He wrote his own screenplays, and led the three-dimensional space rather than stage-painting in the Indian movie. 1921/22, he published the first Indian films and programs designed to even the movie posters. Publicity was not alien to Painter's many talents – in 1921–22, he distributed programme booklets complete with photographs and film details.

Baburao was a man of many talents – he wrote his own screenplays and he was also the first Indian filmmaker to adopt the method, Eisenstein had described as 'stenographic' – he sketched the costumes, movements, and characters. He changed the concept of set designing from painted curtains to solid multi-dimensional lived in spaces, he introduced artificial lighting and understood the importance of publicity. As early as 1921–22 he was the first to issue programme booklets, complete with details of the film and photographs. He also painted himself tasteful, eye-catching posters of his films.[2]

A perfectionist, he insisted upon any number of rehearsals. As Zunzarrao Pawar, a cast member, said '` He would take umpteen rehearsals before actual shooting....but he was very slow in film-making. That was why we used to get annoyed with him sometimes.'`

The advent of sound in 1931 did not excite Painter. However, after a few more silent films, the Maharashtra Film Company pulled down its shutters with the advent of sound. Baburao was not particularly keen on the talkies for he believed that they would destroy the visual culture so painfully evolved over the years.

He returned to painting and sculpture, his original vocation barring sporadic ventures like remaking Savkari Pash in sound in 1936, Pratibha (1937), one of his few preserved films which is a good illustration of Painter's control over big sets, lighting and crowd scenes and Lokshahir Ramjoshi (1947) on Shantaram's invitation.

The beautiful posters that Baburao painted for his films prompted the advice of not wasting his talent on dirty walls, that an art gallery was the correct destination! Prophetic words indeed, because later his posters were up at J.J. School of Art, Mumbai and much admired by the principal, Gladstone Solomon.

Filmography

Actor

- Kalyan Khajina (1924)

- Sinhagad (1923) – Emperor Shivaji

Together, Sinhagad and Kalyan Khajina won a medal at the Wembley Exhibition, London. One newspaper, Daily Express, described the films as full of strangely wistful beauty, and acted with extraordinary grace.

Art Director

- Usha (1935/I)

- Usha (1935/II)

Writer

- Sairandhri (1920)

Cinematographer

- Sairandhri (1920 Hindi film): This episode from the Mahabharata dealt with the slaying of Keechak by Bhima (one of the Pandava princes), and the film was based on the play Keechak Wadh by K.P. Khadilkar. The play itself was banned because of the perceived criticism of Lord Curzon. The intense realism of the killing was horrifying to the audience, and the scenes were deleted.

Director

- Surekha Haran (1921): This was the debut film of V. Shantaram

- Bhagwata Bhakta Damaji (1922)

- Damaji (1922)

- Vatsalaharan (1923)

- Sinhagad (1923): Baburao shifted from painted curtains to multi-dimensional sets. Another first – he used artificial lighting to create the effect of fog and of moonlight. The film was based on Hari Narayan Apte's novel "Gad Aala Pan Sinha Gela" (गड आला पण सिंह गेला). The protagonist Tanaji was a follower of Shivaji and died while capturing Kondhana Fort.While filming Sinhagad, Baburao fell off a horse, the injury causing a lifelong speech defect. Sinhagad proved so popular that it attracted the Revenue Department's attention to bring about introduction of Entertainment Tax.

- Sati Padmini (1924)

- Shri Krishna Avatar (1924)

- Shaha la Shah (1925)

- Rana Hamir (1925)

- Maya Bazaar (1925)

- Savkari Pash (1925): Dealt with money lending and the plight of poor farmers. However the audience long fed on mythological fantasy and historical love was just not prepared for so strong a dose of realism and the film did not do well. Baburao returned to costume dramas. The film failed. Baburao Painter returned to the tried-and-true subject-matter. Painter's artistic masterpiece remains Savkari Pash (1925), dealing with money lending, a problem that blighted the lives of countless illiterate, poor farmers. J.H.Wadia on the two versions of Savkari Pash: I faintly remember the silent Savkari Pash...But it was only when I saw the talkie version that I realised what a great creative artist he (Baburao) was. I go into a trance when I recollect the long shot of a dreary hut photographed in low key, highlighted only by the howl of a dog.[3]

- Bhakta Pralhad (1926/I)

- Gaj Gauri (1926)

- Muraliwala (1927)

- Sati Savitri (1927) ... a.k.a. Savitri Satyavan (Hindi title)

- Netaji Palkar (1927): Directed by V. Shantaram, the film was about Shivaji

- Karna (1928)

- Keechaka Vadha (1928/I) ... a.k.a. Sairandhri (Hindi title) or Valley of the Immortals (English title)

- Baji Prabhu Deshpande (1929)

- Prem Sangam (1931) ... a.k.a. When Lovers Unite (English title)

- Lanka (1930) ... a.k.a. The Land of Lust (English title)

- Usha (1935): The film (a talkie) was directed by Painter for the film company Shalini Cinetone, Kolhapur.

- Remake of Savkari Pash as a talkie (1936)

- Pratibha (1937)

- Sadhvi Meerabai (1937)

- Rukmini Swayamvar (1946/I)

- Rukmini Swayamvar (1946/II) ... a.k.a. The Marriage of Rukmini (English title)

- Lokshahir Ram Joshi (1947) - Marathi, Matwala Shair Ramjoshi(1947) Hindi: A highly successful film.

- Lok Shahir Ram Joshi (1947)

- Vishwamitra (1952)

- Mahajan (1953)

References

- Gulzar; Govind Nihalani; Saibal Chatterjee (2003). Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema: An Enchanting Close-Up of India's Hindi Cinema. Popular Prakashan. p. 549. ISBN 978-81-7991-066-5. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- Hansa Wadkar; Shobha Shinde (1 April 2014). You Ask, I Tell: An autobiography. Zubaan. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-93-83074-68-6.

- "Savkari Pash (1925)". filmheritagefoundation.co.in. Film Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 15 June 2015.