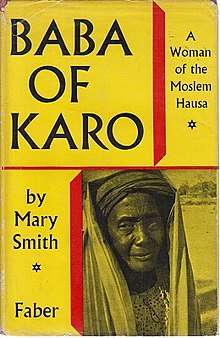

Baba of Karo

Baba of Karo is a 1954 book by the anthropologist Mary F. Smith.[1] The book is an anthropological record of the Hausa people, partly compiled from an oral account given by Baba (1877-1951), the daughter of a Hausa farmer and Koranic teacher. Baba's reports were translated by Smith.[2]

Smith's husband, the anthropologist M. G. Smith, contributed an explanation of the Hausa's cultural context.[1]

The 1981 reissue of Baba of Karo contains a foreword by Hilda Kuper.[2] An extract from the book is included in the 1992 anthology Daughters of Africa.[3]

Baba of Karo's autobiography helped document Nigerian history through a woman's perspective.[4] Not only does Baba depict her own experiences, but she tells stories of important women who were close to her.[2] Recording these experiences was a great feat because Nigerian women were largely undocumented.[4] Baba of Karo's autobiography covers many issues such as prostitution, childbirth, marriage, and life in the compounds in which she lived.[4]

Precolonial life

Baba was born to a Hausa Muslim family in the small African town of Karo. [4] Her birth took place in the 19th century, before the British Empire held much global power. [4] Karo was an agrestic town where harvesting and agriculture were important.[5]

Before British rule, Hausa women could be found harvesting the fields.[5] With capabilities to produce multiple goods, markets filled the streets and trade was a common practice.[5] The compounds in which Hausa people lived told a lot about their social status, depending on the shape and how the compounds were partitioned.[5]

In precolonial Karo, kinships were distinctly bilateral where ties were traced through both parents who typically held equal social weight.[5] However, Baba recalls marriage being virilocal and largely driven by polygamy.[5] This meaning that married women would relocate to their husband's father's compounds.[5]

Postcolonial life

Baba lived through the emancipation of slaves, although it did not seem to have much of an effect on her life.[4] Power structures remained the same even after England's abolition of slavery.[4] Additionally, the Hausa people's traditions, ideas, and social interactions momentarily remained unchanged.[5]

Baba recalled that gender roles were still enforced as boys followed their fathers in the fields and were taught to recite the Koran, while girls were taught how to cook and clean by their mothers.[5]

Although colonialism reached its peak during Baba's lifetime, the integration of new policies and ways of life weren't largely noticed until years later.[4]

References

- Judith Okel and Helen Callaway (eds), Anthropology and Autobiography, Routledge, 1992, pp. 39–40.

- Mary F. Smith, Baba of Karo: A Woman of the Muslim Hausa, Yale University Press, 1981, 300 pp.

- Margaret Busby, "Baba", in Daughters of Africa, Jonathan Cape, 1992,pp. 166–68.

- "Mary F. Smith – Baba of Karo. A woman of the Moslem Hausa". aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- Karo), Baba (of; Smith, Mary Felice (1981). Baba of Karo, a Woman of the Muslim Hausa. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300027419.