Disaster recovery and business continuity auditing

Given organizations' increasing dependency on information technology to run their operations, Business continuity planning covers the entire organization, and Disaster recovery focuses on IT.

Auditing of documents covering an organization's business continuity and disaster recovery plans provides a third-party validation to stakeholders that the documentation is complete and does not contain material misrepresentations.

Lack of completeness can result in overlooking secondary effects, such as when vastly increased work-at-home overloads incoming recovery site telecommunications capacity, and the bi-weekly payroll that was not critical within the first 48 hours is now causing perceived problems in ever recovering, complicated by governmental and possibly union reaction.[1]

Overview

Often used together, the terms Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery are very different. Business Continuity refers to the ability of a business to continue critical functions and business processes after the occurrence of a disaster, whereas Disaster Recovery refers specifically to the Information Technology (IT) and data-centric functions of the business, and is a subset of Business Continuity.[2]

Metrics

The primary objective is to protect the organization in the event that all or part of its operations and/or computer services are rendered partially or completely unusable.

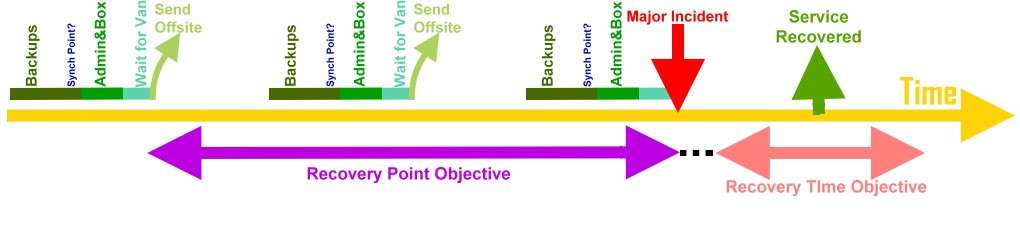

Minimizing downtime and data loss during disaster recovery is measured in terms of two concepts:

- Recovery Time Objective (RTO), time until a system is completely up and running

- Recovery Point Objective (RPO), a measure of the ability to recover files by specifying a point in time restore of the backup copy.

The auditor's role

An auditor examines and assess

- that the procedures stated in the BCP and DR plan are actually consistent with real practice

- that a specific individual within the organization, who may be referred to as the disaster recovery officer, the disaster recovery liaison, the DR coordinator, or some other similar title, has the technical skills, training, experience, and abilities to analyze the capabilities of the team members to complete assigned tasks

- that more than one individual is trained and capable of doing a particular function. Tests and inquiries of personnel can help achieve this objective.

Documentation

To maximize their effectiveness, disaster recovery plans are most effective when updated frequently, and should:

- be an integral part of all business analysis processes,

- be revisited at every major corporate acquisition, at every new product launch and at every new system development milestone.

Adequate records need to be retained by the organization. The auditor examines records, billings, and contracts to verify that records are being kept. One such record is a current list of the organization's hardware and software vendors. Such list is made and periodically updated to reflect changing business practice. Copies of it are stored on and off site and are made available or accessible to those who require them. An auditor tests the procedures used to meet this objective and determine their effectiveness.

Disaster recovery plan

A disaster recovery plan (DRP) is a documented process or set of procedures to execute an organization's disaster recovery processes and recover and protect a business IT infrastructure in the event of a disaster.[3] It is "a comprehensive statement of consistent actions to be taken before, during and after a disaster".[4] The disaster could be natural, environmental or man-made. Man-made disasters could be intentional (for example, an act of a terrorist) or unintentional (that is, accidental, such as the breakage of a man-made dam).

Types of plans

Although there is no one-size-fits-all plan,[5] there are three basic strategies:[3][5]

- prevention, including proper backups, having surge protectors and generators

- detection, a byproduct of routine inspections, which may discover new (potential) threats

- correction[6]

The latter may include securing proper insurance policies, and holding a "lessons learned" brainstorming session.[3][7]

Relationship to the Business Continuity Plan

The Business Continuity Plan (BCP) is a comprehensive organizational plan that includes the disaster recovery plan, and it consists of five component plans:[8]

- Business Resumption Plan

- Occupant Emergency Plan

- Continuity of Operations Plan

- Incident Management Plan

- Disaster Recovery Plan

The first three (Business Resumption, Occupant Emergency, and Continuity of Operations Plans) do not deal with the IT infrastructure. The Incident Management Plan (IMP) does deal with the IT infrastructure, but since it establishes structure and procedures to address cyber attacks against an organization’s IT systems, it generally does not represent an agent for activating the Disaster Recovery Plan, leaving The Disaster Recovery Plan as the only BCP component of interest to IT.[8]

Benefits

Like every insurance plan, there are benefits that can be obtained from proper planning, including:[4]

- Minimizing risk of delays

- Guaranteeing the reliability of standby systems

- Providing a standard for testing the plan

- Minimizing decision-making during a disaster

- Reducing potential legal liabilities

- Lowering unnecessarily stressful work environment

Planning and testing methodology

According to Geoffrey H. Wold of the Disaster Recovery Journal, the entire process involved in developing a Disaster Recovery Plan consists of 10 steps:[4]

- Performing a risk assessment: The planning committee prepares a risk analysis and a business impact analysis (BIA) that includes a range of possible disasters. Each functional area of the organization is analyzed to determine potential consequences. Traditionally, fire has posed the greatest threat. A thorough plan provides for "worst case" situations, such as destruction of the main building.

- Establishing priorities for processing and operations: Critical needs of each department are evaluated and prioritized. Written agreements for alternatives selected are prepared, with details specifying duration, termination conditions, system testing, cost, any special security procedures, procedure for the notification of system changes, hours of operation, the specific hardware and other equipment required for processing, personnel requirements, definition of the circumstances constituting an emergency, process to negotiate service extensions, guarantee of compatibility, availability, non-mainframe resource requirements, priorities, and other contractual issues.

- Collecting data: This includes various lists (employee backup position listing, critical telephone numbers list, master call list, master vendor list, notification checklist), inventories (communications equipment, documentation, office equipment, forms, insurance policies, workgroup and data center computer hardware, microcomputer hardware and software, office supply, off-site storage location equipment, telephones, etc.), distribution register, software and data files backup/retention schedules, temporary location specifications, any other such lists, materials, inventories, and documentation. Pre-formatted forms are often used to facilitate the data gathering process.

- Organizing and documenting a written plan

- Developing testing criteria and procedures: reasons for testing include

- Determining the feasibility and compatibility of backup facilities and procedures.

- Identifying areas in the plan that need modification.

- Providing training to the team managers and team members.

- Demonstrating the ability of the organization to recover.

- Providing motivation for maintaining and updating the disaster recovery plan.

- Testing the plan: An initial "dry run" of the plan is performed by conducting a structured walk-through test. An actual test-run must be performed. Problems are corrected.

Initial testing can be plan is done in sections and after normal business hours to minimize disruptions. Subsequent tests occur during normal business hours.

Types of tests include: checklist tests, simulation tests, parallel tests, and full interruption tests.

Caveats/controversies

Due to high cost, various plans are not without critics. Dell has identified five "common mistakes" organizations often make related to BCP/DR planning:[9]

- Lack of buy-in: When executive management sees DR planning as "just another fake earthquake drill" or CEOs fail to make DR planning and preparation a priority

- Incomplete RTOs and RPOs: Failure to include each and every important business process or a block of data. Ripples can extend a disaster's impact. Payroll may not initially be mission-critical, but left alone for several days, it can become more important than any of your initial problems.

- Systems myopia: A third point of failure involves focusing only on DR without considering the larger business continuity needs. Corporate office space lost to a disaster can result in an instant pool of teleworkers which, in turn, can overload a company's VPN overnight, overwork the IT support staff at the blink of an eye and cause serious bottlenecks and monopolies with the dial-in PBX system.

- Lax security: When there is a disaster, an organization's data and business processes become vulnerable. As such, security can be more important than the raw speed involved in a disaster recovery plan's RTO. The most critical consideration then becomes securing the new data pipelines: from new VPNs to the connection from offsite backup services.

- In disasters, planning for post-mortem forensics

- Locking down or remotely wiping lost handheld devices

Decisions and Strategies

- Site designation: hot site vs. cold site. A hot site is fully equipped to resume operations while a cold site does not have that capability. A warm site has the capability to resume some, but not all operations.

A cost-benefit analysis is needed.

- Occasional tests and trials verify the viability and effectiveness of the plan. An auditor looks into the probability that operations of the organization can be sustained at the level that is assumed in the plan, and the ability of the entity to actually establish operations at the site.

- The auditor can verify this through paper and paperless documentation and actual physical observation. The security of the storage site is also confirmed.

- Data backup: An audit of backup processes determines if (a) they are effective, and (b) if they are actually being implemented by the involved personnel.[10][11]

The disaster recovery plan also includes information on how best to recover any data that has not been copied. Controls and protections are put in place to ensure that data is not damaged, altered, or destroyed during this process.

- Drills: Practice drills conducted periodically to determine how effective the plan is and to determine what changes may be necessary. The auditor’s primary concern here is verifying that these drills are being conducted properly and that problems uncovered during these drills are addressed.

- Backup of key personnel - including periodic training and cross-training.

Other considerations

Insurance issues

The auditor determines the adequacy of the company's insurance coverage (particularly property and casualty insurance) through a review of the company's insurance policies and other research. Among the items that the auditor needs to verify are: the scope of the policy (including any stated exclusions), that the amount of coverage is sufficient to cover the organization’s needs, and that the policy is current and in force. The auditor also ascertains, through a review of the ratings assigned by independent rating agencies, that the insurance company or companies providing the coverage have the financial viability to cover the losses in the event of a disaster.

Effective DR plans take into account the extent of a company's responsibilities to other entities and its ability to fulfill those commitments despite a major disaster. A good DR audit will include a review of existing MOA and contracts to ensure that the organization's legal liability for lack of performance in the event of disaster or any other unusual circumstance is minimized. Agreements pertaining to establishing support and assisting with recovery for the entity are also outlined. Techniques used for evaluating this area include an examination of the reasonableness of the plan, a determination of whether or not the plan takes all factors into account, and a verification of the contracts and agreements reasonableness through documentation and outside research.

Communication issues

The auditor must verify that planning ensures that both management and the recovery team have effective communication hardware, contact information for both internal communication and external issues, such as business partners and key customers.

Audit techniques include

- testing of procedures, interviewing employees, making comparison against the plans of other company and against industry standards,

- examining company manuals and other written procedures.

- direct observation that emergency telephone numbers are listed and easily accessible in the event of a disaster.

Emergency procedures

Procedures to sustain staff during a round-the clock disaster recovery effort are included in any good disaster recovery plan. Procedures for the stocking of food and water, capabilities of administering CPR/first aid, and dealing with family emergencies are clearly written and tested. This can generally be accomplished by the company through good training programs and a clear definition of job responsibilities. A review of the readiness capacity of a plan often includes tasks such as inquires of personnel, direct physical observation, and examination of training records and any certifications.

Environmental issues

The auditor must review procedures that take into account the possibility of power failures or other situations that are of a non-IT nature.

- Flashlights and candles may be needed.

- Safety procedures in case of gas leaks, fires or other such phenomena

See also

References

- "Are External Auditors Concerned about Cyber Risk disclosure" (PDF).

- Susan Snedaker (2013). Business continuity and disaster recovery planning for IT professionals (2 ed.). Burlington: Elsevier Science. ISBN 9780124114517.

- Bill Abram (14 June 2012). "5 Tips to Build an Effective Disaster Recovery Plan". Small Business Computing. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Wold, Geoffrey H. (1997). "Disaster Recovery Planning Process". Disaster Recovery Journal. Adapted from Volume 5 #1. Disaster Recovery World. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- "Disaster Recovery Planning - Step by Step Guide". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- "Backup Disaster Recovery". Email Archiving and Remote Backup. 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- "Disaster Recovery & Business Continuity Plans". Stone Crossing Solutions. 2012. Archived from the original on 23 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Chad Bahan. (June 2003). "The Disaster Recovery Plan". Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- Cormac Foster; Dell Corporation (25 October 2010). "Five Mistakes That Can Kill a Disaster Recovery Plan". Archived from the original on 2013-01-16. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- Constance Gustke (October 7, 2015). "Hurricane Joaquin Highlights the Importance of Plans to Keep Operating". The New York Times.

- Berman, Alan. Constructing a Successful Business Continuity Plan. Business Insurance Magazine, March 9, 2015. http://www.businessinsurance.com/article/20150309/ISSUE0401/303159991/constructing-a-successful-business-continuity-plan

- Messier, Jr., W. F. (2011). Auditing & Assurance Services: A Systematic Approach (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN 9780077520151.

- Gallegos, F.; Senft, S.; Davis, A. L. (2012). Information Technology Control and Audit (4th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: Auerbach Publications. ISBN 9781439893203.