Azathoth

Azathoth is a deity in the Cthulhu Mythos and Dream Cycle stories of writer H. P. Lovecraft and other authors. He is the ruler of the Outer Gods,[1] and may be seen as a symbol for primordial chaos.[2]

| Azathoth | |

|---|---|

| Cthulhu Mythos character | |

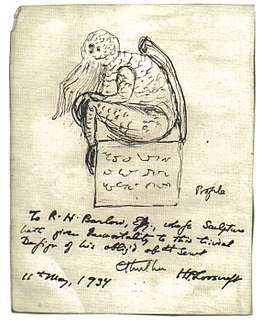

Artist's depiction of Azathoth | |

| First appearance | "Azathoth" |

| Created by | H. P. Lovecraft |

| In-universe information | |

| Species | Outer God |

| Title | Nuclear Chaos Daemon Sultan Blind Idiot God |

| Children | Nyarlathotep (son) Nameless Mist (offspring) Darkness (offspring) |

| Relatives | Yog-Sothoth (grandson) Shub-Niggurath (granddaughter) Nug (great-grandchild) Yeb (great-grandchild) Wilbur Whateley (great-grandson) Cthulhu (great-great-grandson) Tsathoggua (great-great-grandson) |

H. P. Lovecraft

Inspiration

The first recorded mention of the name Azathoth was in a note Lovecraft wrote to himself in 1919 that read simply, "AZATHOTH—hideous name". Mythos editor Robert M. Price argues that Lovecraft could have combined the biblical names Anathoth (Jeremiah's home town) and Azazel—mentioned by Lovecraft in "The Dunwich Horror".[3] Price also points to the alchemical term "Azoth", which was used in the title of a book by Arthur Edward Waite, the model for the wizard Ephraim Waite in Lovecraft's "The Thing on the Doorstep".[4]

Another note Lovecraft made to himself later in 1919 refers to an idea for a story: "A terrible pilgrimage to seek the nighted throne of the far daemon-sultan Azathoth."[5] In a letter to Frank Belknap Long, Lovecraft ties this plot germ to Vathek, a novel by William Beckford about a supernatural caliph.[6] Lovecraft's attempts to work this idea into a novel foundered (a 500-word fragment survives, first published under the title "Azathoth"[7] in the journal Leaves in 1938),[8] although Lovecraftian scholar Will Murray suggests that Lovecraft recycled the idea into his Dream Cycle novella The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, written in 1926.[9]

Price sees another inspiration for Azathoth in Lord Dunsany's Mana-Yood-Sushai, from The Gods of Pegana, a creator deity "who made the gods and thereafter rested." In Dunsany's conception, MANA-YOOD-SUSHAI sleeps eternally, lulled by the music of a lesser deity who must drum forever, "for if he cease for an instant then MANA-YOOD-SUSHAI will start awake, and there will be worlds nor gods no more." This oblivious creator god accompanied by supernatural musicians is a clear prototype for Azathoth, Price argues.[10]

Fiction

Aside from the title of the novel fragment, The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath was the first fiction by Lovecraft to mention Azathoth:

[O]utside the ordered universe [is] that amorphous blight of nethermost confusion which blasphemes and bubbles at the center of all infinity—the boundless daemon sultan Azathoth, whose name no lips dare speak aloud, and who gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time and space amidst the muffled, maddening beating of vile drums and the thin monotonous whine of accursed flutes.[11]

Lovecraft referred to Azathoth again in "The Whisperer in Darkness" (1931), where the narrator relates that he "started with loathing when told of the monstrous nuclear chaos beyond angled space which the Necronomicon had mercifully cloaked under the name of Azathoth".[12][13] Here "nuclear" most likely refers to Azathoth's central location at the nucleus of the cosmos and not to nuclear energy, which did not truly come of age until after Lovecraft's death.

In "The Dreams in the Witch House" (1932), the protagonist Walter Gilman dreams that he is told by the witch Keziah Mason that "He must meet the Black Man, and go with them all to the throne of Azathoth at the centre of ultimate Chaos.... He must sign in his own blood the book of Azathoth and take a new secret name.... What kept him from going with her...to the throne of Chaos where the thin flutes pipe mindlessly was the fact that he had seen the name 'Azathoth' in the Necronomicon, and knew it stood for a primal horror too horrible for description."[14] Gilman wakes from another dream remembering "the thin, monotonous piping of an unseen flute", and decides that "he had picked up that last conception from what he had read in the Necronomicon about the mindless entity Azathoth, which rules all time and space from a curiously environed black throne at the centre of Chaos".[15] He later fears finding himself "in the spiral black vortices of that ultimate void of Chaos wherein reigns the mindless daemon-sultan Azathoth".[16]

The poet Edward Pickman Derby, the protagonist of Lovecraft's "The Thing on the Doorstep", is a poet whose collection of "nightmare lyrics" is called Azathoth and Other Horrors.[17]

The last major reference in Lovecraft's fiction to Azathoth was in 1935's "The Haunter of the Dark", which tells of "the ancient legends of Ultimate Chaos, at whose center sprawls the blind idiot god Azathoth, Lord of All Things, encircled by his flopping horde of mindless and amorphous dancers, and lulled by the thin monotonous piping of a demonic flute held in nameless paws".[18]

In a letter to a friend who jokingly claimed descent from Jupiter, Lovecraft drew up a detailed genealogy charting his and fellow novelist Clark Ashton Smith's shared descent from Azathoth, through Lovecraft's creation Nyarlathotep and Clark-Smith's Tsathoggua, respectively. As nowhere stated in Lovecraft's published work, primordial Azathoth here is made ancestor, through his children Nyarlathotep, "The Nameless Mist," and "Darkness," of Yog-Sothoth, Shub-Niggurath, Nug and Yeb, Cthulhu, Tsathoggua, several deities and monsters unmentioned outside the letter, and a few of Lovecraft's and Ashton-Smith's fancifully-posited human forebears.[19]

Other writers

August Derleth

Many other Mythos writers have referred to Azathoth in their stories. August Derleth, in his novel The Lurker at the Threshold, depicts the entity as a leader in a cosmic upheaval akin to Lucifer's rebellion in Christian mythology. In a passage attributed to the Necronomicon of Abdul Alhazred, Derleth writes:

(T)hose daring to oppose the Elder Gods who ruled from Betelgueze, the Great Old Ones who fought against the Elder Gods...were instructed by Azathoth, who is the blind idiot god, and by Yog-Sothoth....[20]

In another passage, Derleth quotes a prophecy:

(Y)e blind idiot, ye noxious Azathoth shal arise from ye middle of ye World where all is Chaos & Destruction where He hath bubbl'd and blasphem'd at Ye centre which is of All Things, which is to say Infinity....

The Elder Gods punished Azathoth by rendering him mindless and blind, according to Derleth.

Ramsey Campbell

In "The Insects from Shaggai", Ramsey Campbell describes the extraterrestrial creatures of the title as worshippers of "the hideous god Azathoth", practicing "obscene rites" that involved "atrocities practiced on still-living victims" in Azathoth's conical temple. After fleeing from the destruction of their home planet of Shaggai, the insects teleported the temple across the universe, eventually ending up in a forest near Campbell's fictional town of Goatswood.[21]

Ronald Shea, the narrator of Campbell's story, enters the temple after visiting the forest and discovers a twenty-foot idol that "represented the god Azathoth—Azathoth as he had been before his exile Outside":

[I]t consisted of a bivalvular shell supported on many pairs of flexible legs. From the half-open shell rose several jointed cylinders, tipped with polypous appendages; and in the darkness inside the shell I thought I saw a horrible bestial, mouthless face, with deep-sunk eyes and covered with glistening black hair.[22]

At the story's climax, Shea catches a glimpse of "what the idiot god might now resemble":

I saw something ooze into the corridor—a pale grey shape, expanding and crinkling, which glistened and shook gelatinously as still-moving particles dropped free; but it was only a glimpse, and after that it is only in nightmares that I imagine I see the complete shape of Azathoth.[23]

In "The Mine on Yuggoth", Edward Taylor had found Azathoth's other name, N______ (not given in full) in the Revelations of Glaaki. If one is confronted by a mythos being, the name, if spoken, will scare it away. Edward Taylor fails to use it.

Gary Myers

Gary Myers makes frequent mention of Azathoth in his stories, both those set in the Lovecraftian Dreamlands and those set in the waking world. In "The Snout in the Alcove" (1977), the dreamer protagonist is distressed to find himself in the Dreamlands to which he had vowed never to return. He had made his vow because of a prophecy which said that:

[P]resently the benign Elder Ones would be deposed by infinity’s Other Gods, who would drag the world down a black spiral vortex to the central void where the demon sultan Azathoth gnaws hungrily in the dark....[24]

In "The Last Night of Earth" (1995), the Dreamlands sorcerer Han briefly ponders:

[T]he allegorical figure of Azathoth, the primal monster who had given birth to the stars at the beginning of time, and who, according to an obscure tradition, would devour them at its end.[25]

In "The Web" (2003), the two teen protagonists read this passage from an internet version of the Necronomicon:

Azathoth is the Greatest God, who rules all infinity from his throne at the center of chaos. His body is composed of all the bright stars of the visible universe, but his face is veiled in darkness.[26]

Thomas Ligotti

Thomas Ligotti's short story "The Sect of the Idiot" (1988) mentions a circle of non-human worshippers composed of wizened, hideous creatures. The story's epigram—a "quotation" from the Necronomicon—reads "The primal chaos, Lord of all... the blind idiot god—Azathoth," suggesting that it is that entity whom the creatures worship.[27]

Ligotti has stated that many of his short stories make allusions to Lovecraft's Azathoth, although rarely by that name. An example of this is the story "Nethescurial", which portrays an omnipresent, malevolent, creator deity once worshipped by the inhabitants of a small island. This being slowly infiltrates the life of the story's narrator, first via a manuscript describing its cult.

Nick Mamatas

Nick Mamatas's 2004 novel Move Under Ground, set in a world where Cthulhu has taken power and only the Beats oppose him, the power of the Great Old Ones twists the constellations into new shapes, using them as vessels for his surrogates; among them, Jack Kerouac observes the "red stars of Azathoth". Neal Cassady later becomes a chosen one of Azathoth, gaining immense powers to be used against Cthulhu in the process.

Call of Cthulhu role-playing game

In the Call of Cthulhu RPG, Azathoth is categorized as an Outer God together with Nyarlathotep, Yog-Sothoth, and others.

The Azathoth Cycle

In 1995, Chaosium published The Azathoth Cycle, a Cthulhu Mythos anthology focusing on works referring to or inspired by the entity Azathoth. Edited by Lovecraft scholar Robert M. Price, the book includes an introduction by Price tracing the roots and development of the Blind Idiot God. The contents include:

- "Azathoth" by Edward Pickman Derby

- "Azathoth in Arkham" by Peter Cannon

- "The Revenge of Azathoth" by Peter Cannon

- "The Pit of the Shoggoths" by Stephen M. Rainey

- "Hydra" by Henry Kuttner

- "The Madness Out of Time" by Lin Carter

- "The Insects from Shaggai" by Ramsey Campbell

- "The Sect of the Idiot" by Thomas Ligotti

- "The Throne of Achamoth" by Richard L. Tierney & Robert M. Price

- "The Last Night of Earth" by Gary Myers

- "The Daemon-Sultan" by Donald R. Burleson

- "Idiot Savant" by C. J. Henderson

- "The Space of Madness" by Stephen Studach

- "The Nameless Tower" by John Glasby

- "The Plague Jar" by Allen Mackey

- "The Old Ones’ Promise of Eternal Life" by Robert M. Price

References

- Steadman, John L. (2015). H.P. Lovecraft and the Black Magickal Tradition: The Master of Horror's Influence on Modern Occultism. Weiser Books. p. 125. ISBN 978-1578635870. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Bilstad, T. Allan (2009). he Lovecraft Necronomicon Primer: A Guide to the Cthulhu Mythos. Llewellyn Publications. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-0738713793. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- H. P. Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", The Dunwich Horror and Others, p. 158.

- Robert M. Price, The Azathoth Cycle, pp. v-vi.

- cited in Price, The Azathoth Cycle, p. vi.

- Letter to Frank Belknap Long, June 9, 1922; cited in Price, The Azathoth Cycle, p. vi.

- "H. P. Lovecraft's original fragment, 'Azathoth'" Archived 2007-08-14 at the Wayback Machine

- "Publication History for H. P. Lovecraft's 'Azathoth'", The H. P. Lovecraft Archive.

- Price, The Azathoth Cycle, p. vii.

- Price, The Azathoth Cycle, pp. viii-ix.

- H. P. Lovecraft, The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, in At The Mountains of Madness, p. 308.

- H. P. Lovecraft, "The Whisperer in Darkness", The Dunwich Horror and Others, p. 256.

- Harman, Graham (2012). Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy. Zero Books. p. 235. ISBN 978-1780992525. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- H. P. Lovecraft, "The Dreams in the Witch House", At the Mountains of Madness, pp. 272–273.

- Lovecraft, "The Dreams in the Witch House", p. 282.

- Lovecraft, "The Dreams in the Witch House", p. 293.

- H. P. Lovecraft, "The Thing on the Doorstep", The Dunwich Horror and Others, p. 277.

- H. P. Lovecraft, "The Haunter of the Dark", The Dunwich Horror and Others, p. 110.

- Lovecraft, H. P. (1967). Selected Letters of H. P. Lovecraft IV (1932–1934). Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House. Letter 617. ISBN 0-87054-035-1.

- August Derleth, The Lurker at the Threshold, in The Watchers Out of Time, p. 133.

- Ramsey Campbell, "The Insects from Shaggai", The Azathoth Cycle, pp. 86-87.

- Campbell, "The Insects from Shaggai", pp. 89, 91.

- Campbell, "The Insects from Shaggai", pp. 91-92.

- Gary Myers, "The Snout in the Alcove", The Year's Best Fantasy Stories 3, pp. 205-206.

- Myers, "The Last Night of Earth", The Azathoth Cycle, p. 132.

- Myers, "The Web", The Disciples of Cthulhu II, p. 54.

- Thomas Ligotti, "The Sect of the Idiot" (1988), The Azathoth Cycle, 93–102.

Sources

- Harms, Daniel (1998). The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana (2nd ed.). Oakland, CA: Chaosium. ISBN 1-56882-119-0.

- Petersen, Sandy. Call of Cthulhu (5th ed.). Oakland, CA: Chaosium. ISBN 1-56882-148-4.

- Price, Robert M. (ed.) (1995). The Azathoth Cycle (1st ed.). Oakland, CA: Chaosium. ISBN 1-56882-040-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

External links