Avantibai

Avantibai (or Avanti Bai; died 20 March 1858) is lauded by members of the [Lodhi] community in India as a freedom fighter and queen of what is now Dindori in Madhya Pradesh, which in her time was called Ramgarh. An opponent of the British East India Company during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, information concerning her is sparse and mostly comes from folklore. Through this she is claimed to have been a member of the Lodhi caste of other backward classes and has been used as an icon in backward politics in the 21st century.

British interference

Said in folklore to be a member of the Lodhi caste,[1] Avantibai was the queen of Vikramaditya Singh of Ramgarh estate,[2] which now lies in Dindori district, Madhya Pradesh.[3] Upon the death of her husband in 1851, Avantibai attempted to act as regent for her son, Amar Singh, who was a minor. The British authorities did not accept this and the Court of Wards appointed an administrator to oversee his affairs.[2]

Indian rebellion of 1857

When the revolt of 1857 broke out, Avantibai raised and led an army of 4000. Her first battle with the British took place in the village of Kheri near Mandla, where she and her army were able to defeat the British forces. However, stung by the defeat the British came back with vengeance and launched an attack on Ramgarh. Avantibai moved to the hills of Devharigarh for safety. The British army set fire to Ramgarh, and turned to Devhargarh to attack the queen.[4]

Avantibai resorted to guerilla warfare to fend of the British army.[4] She committed suicide with her sword on 20 March 1858 when facing almost certain defeat in battle.

Legacy

After independence, Avantibai has been remembered through performances and folklore.[5] A folk song of the Gondi people, an adivasi tribe of the region, says:[6]

The Rani who is our mother, strikes repeatedly at the British. / She is the chief of the jungles. / She sent letters and bangles to other (rulers, chieftains) and aligned them to the cause. / She vanquished and pushed the Britishers out, / in every street she made them panic, / so that they ran away wherever they could find their way. / Whenever she entered the battleground on horseback,/she fought bravely and swords and spears ruled the day. / O, she was our Rani mother

She is among the viranganas (heroic women) lauded by Dalit groups as part of an invented tradition surrounding the events of 1857, other examples of whom include Asha Devi, Jhalkari Bai, Mahabiri Devi and Uda Devi. Charu Gupta notes of these traditions that "scattered, often thin, evidence is cited and quoted by Dalits repeatedly".[1]

Although little is known of Avantibai except through folklore, her story merited a brief inclusion in the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) history textbooks from 2012 as a participant in the 1857 rebellion, after parliamentary protests from the Bharatiya Janata Party and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP).[7][8] The BSP, in particular, had been using the story of Avantibai, along with accounts of other Dalit folk heroines, as a means to promote the image of Mayawati,[5] with her biographer, Ajoy Bose, noting that she is cast as their "modern avatar".[9]

The Narmada Valley Development Authority named a part of the Bargi Dam project in Jabalpur in her honour.[10]

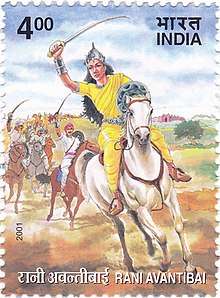

India Post has issued two stamps in honour of Avantibai, on 20 March 1988 and on 19 September 2001.[11][12]

See also

References

- Gupta, Charu (2014). "Condemnation and Commemoration: (En)Gendering Dalit Narratives of 1857". In Bates, Crispin (ed.). Mutiny at the Margins: New Perspectives on the Indian Uprising of 1857. V: Muslim, Dalit and Subaltern Narratives. SAGE Publishing India. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-8-13211-902-9.

- Gupta, Amit Kumar (2015). Nineteenth-Century Colonialism and the Great Indian Revolt. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-31738-669-8.

- "Mandla". Government of Madhya Pradesh. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Sarala, Śrīkr̥shṇa (1999). Indian Revolutionaries A Comprehensive Study, 1757–1961. 1. Ocean Books. p. 79. ISBN 81-87100-16-8.

- Narayan, Badri (2006). Women Heroes and Dalit Assertion in North India: Culture, Identity, and Politics. SAGE Publications. pp. 26, 48, 79, 86. ISBN 978-8-17829-695-1.

- Pati, Biswamoy (29 September 2017). "India 'Mutiny' and 'Revolution,' 1857-1858". Oxford Bibliographies. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199791279-0040. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Chopra, Ritika (19 May 2012). "NCERT includes Rani Avantibai Lodhi in school textbooks under political pressure". India Today. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "When People Rebel: 1857 and After". Our Pasts (PDF). III. NCERT. pp. 58–59.

- Bose, Ajoy (2009). Behenji: A Political Biography of Mayawati. Penguin UK. p. 290. ISBN 978-8-18475-650-0.

- "Rani Avanti Bai Sagar" (PDF). nvda.nic.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- 19 September 2001: A commemorative postage stamp on Rani Avantibai. postagestamps.gov.in

- "Rani Avantibai 1988". iStampGallery.com. 11 February 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

Further reading

- Gupta, Charu (May 2007). "Dalit 'Viranganas' and Reinvention of 1857". Economic and Political Weekly. 42 (19): 1739–1745. JSTOR 4419579.