Aurora Generator Test

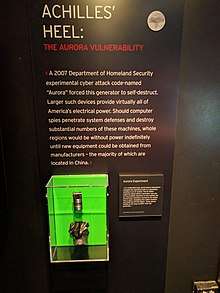

Idaho National Laboratory ran the Aurora Generator Test in 2007 to demonstrate how a cyberattack could destroy physical components of the electric grid.[1] The experiment used a computer program to rapidly open and close a diesel generator's circuit breakers out of phase from the rest of the grid and cause it to explode. This vulnerability is referred to as the Aurora Vulnerability.

This vulnerability is especially a concern because much grid equipment supports using Modbus and other legacy communications protocols that were designed without security in mind. As such, they don't support authentication, confidentiality, or replay protection, which means any attacker that can communicate with the device can control it and use the Aurora Vulnerability to destroy it.

Experiment

To prepare for the experiment, the researchers procured and installed a 2.25 MW generator and connected it to the substation. They also needed access to a programmable digital relay or another device that controls the breaker. That access could have been through a mechanical or digital interface.[2]

In the experiment, the researchers used a cyberattack to open and close the breakers out of sync, to maximize the stress. Each time the breakers were closed, the torque from the synchronization caused the generator to bounce and shake, eventually causing parts of the generator be to ripped apart and sent flying off.[3] Some parts of the generator landed as far as 80 feet away from the generator.[4]

The unit was destroyed in roughly three minutes. However, this was only because the researchers assessed the damage from each iteration of the attack. A real attack could have destroyed the unit much more quickly.[3]

The experiment was designated as unclassified, for official use only.[5] On September 27, 2007, CNN published an article based on the information and video DHS released to them,[1] and on July 3, 2014, DHS released many of the documents related to the experiment as part of an unrelated FOIA request.[6]

Vulnerability

The Aurora vulnerability is caused by the out-of-sync closing of the protective relays.[3]

"A close, but imperfect, analogy would be to imagine the effect of shifting a car into Reverse while it is being driven on a highway, or the effect of revving the engine up while the car is in neutral and then shifting it into Drive."[3]

"The Aurora attack is designed to open a circuit breaker, wait for the system or generator to slip out of synchronism, and reclose the breaker, all before the protection system recognizes and responds to the attack... Traditional generator protection elements typically actuate and block reclosing in about 15 cycles. Many variables affect this time, and every system needs to be analyzed to determine its specific vulnerability to the Aurora attack... Although the main focus of the Aurora attack is the potential 15-cycle window of opportunity immediately after the target breaker is opened, the overriding issue is how fast the generator moves away from system synchronism."[7]

Potential impact

The failure of even a single generator could cause widespread outages and possibly cascading failure of the entire power grid, as occurred in the Northeast blackout of 2003. Additionally, even if there are no outages from the removal of a single component (N-1 resilience), there is a large window for a second attack or failure, as it could take more than a year to replace a destroyed generator, because many generators and transformers are custom-built.

Mitigations

The Aurora vulnerability can be mitigated by preventing the out-of-phase opening and closing of the breakers. Some suggested methods include adding functionality in protective relays to ensure synchronism and adding a time delay for closing breakers.[8]

One mitigation technique is to add a synchronism-check function to all protective relays that potentially connect two systems together. To implement this, the function must prevent the relay from closing unless the voltage and frequency are within a pre-set range.

Devices such as the IEEE 25 Sync-Check relay and IEEE 50 can be used to prevent out-of-phase opening and closing of the breakers.[9]

Criticisms

There was some discussion as to whether Aurora hardware mitigation devices (HMD) can cause other failures. In May 2011, Quanta Technology published an article that used RTDS (Real Time Digital Simulator) testing to examine the "performance of multiple commercial relay devices available" of Aurora HMDs. To quote: "The relays were subject to different test categories to find out if their performance is dependable when they need to operate, and secure in response to typical power system transients such as faults, power swing and load switching... In general, there were technical shortcomings in the protection scheme’s design that were identified and documented using the real time testing results. RTDS testing showed that there is, as yet, no single solution that can be widely applied to any case, and that can present the required reliability level."[10] A presentation from Quanta Technology and Dominion succinctly stated in their reliability assessment "HMDs are not dependable, nor secure."[11]

Joe Weiss, a cybersecurity and control system professional, disputed the findings from this report and claimed that it has misled utilities. He wrote: "This report has done a great deal of damage by implying that the Aurora mitigation devices will cause grid issues. Several utilities have used the Quanta report as a basis for not installing any Aurora mitigation devices. Unfortunately, the report has several very questionable assumptions. They include applying initial conditions that the hardware mitigation was not designed to address such as slower developing faults, or off nominal grid frequencies. Existing protection will address “slower” developing faults and off nominal grid frequencies (<59 Hz or >61 Hz). The Aurora hardware mitigation devices are for the very fast out-of-phase condition faults that are currently gaps in protection (i.e., not protected by any other device) of the grid."[12]

Timeline

On March 4, 2007, Idaho National Laboratory demonstrated the Aurora vulnerability.[13]

On June 21, 2007, NERC notified industry about the Aurora vulnerability.[14]

On September 27, 2007, CNN released a previously-classified demonstration video of the Aurora attack on their homepage.[1] That video can be downloaded from here.

On October 13, 2010, NERC released a recommendation to industry on the Aurora vulnerability.[14]

On July 3, 2014, the US Department of Homeland Security released 840 pages of documents related to Aurora.[6]

See also

References

- "Mouse click could plunge city into darkness, experts say". CNN. September 27, 2007. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "FOIA Request - Operation Aurora" (PDF). Muckrock. p. 91. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "FOIA Request - Operation Aurora" (PDF). Muckrock. p. 59. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "Master Script" (PDF). INTERNATIONAL SPY MUSEUM. p. 217. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "FOIA Request - Operation Aurora" (PDF). Muckrock. p. 134. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "FOIA Request - Operation Aurora". Muckrock. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Zeller, Mark. "Common Questions and Answers Addressing the Aurora Vulnerability". Schweitzer Engineering Laboratories, Inc. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Zeller, Mark. "Myth or Reality – Does the Aurora Vulnerability Pose a Risk to My Generator?". Schweitzer Engineering Laboratories, Inc. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "Avoiding unwanted reclosing on rotating apparatus (Aurora)" (PDF). Power System Relaying and Control Committee. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "QT e-News" (PDF). Quanta Technology. p. 3. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "Aurora Vulnerability Issues & Solutions Hardware Mitigation Devices (HMDs)" (PDF). Quanta Technology. July 24, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "Latest Aurora information – this affects ANY electric utility customer with 3-phase rotating electric equipment!". Unfettered Blog. September 4, 2013. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "U.S. video shows hacker hit on power grid". USA Today. September 27, 2007. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "NERC Issues AURORA Alert to Industry" (PDF). NERC. October 14, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-12. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

External links

- http://www.langner.com/en/2014/07/09/aurora-revisited-by-its-original-project-lead/

- http://www.powermag.com/what-you-need-to-know-and-dont-about-the-aurora-vulnerability/?printmode=1

- http://breakingenergy.com/2013/09/13/the-all-too-real-cyberthreat-nobody-is-prepared-for-aurora/

- http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9039678/Simulated_attack_points_to_vulnerable_U.S._power_infrastructure

- http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9249642/New_docs_show_DHS_was_more_worried_about_critical_infrastructure_flaw_in_07_than_it_let_on

- http://threatpost.com/dhs-releases-hundreds-of-documents-on-wrong-aurora-project

- http://news.infracritical.com/pipermail/scadasec/2014-July/thread.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20140903052039/http://www.thepresidency.org.70-32-102-141.pr6m-p7xj.accessdomain.com/sites/default/files/Grid%20Report%20July%2015%20First%20Edition.pdf (Page 30)

- http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2007-09/27/content_6139437.htm

- http://www.infosecisland.com/blogview/20925-Misconceptions-about-Aurora-Why-Isnt-More-Being-Done.html

- https://www.sce.com/wps/wcm/connect/c5fe765f-f66b-4d37-8e9f-7911fd6e7f3b/AURORACustomerOutreach.pdf?MOD=AJPERES