Augustin Mouchot

Augustin Mouchot (/muːˈʃoʊ/; French: [muʃo]; 7 April 1825 – 4 October 1912) was a 19th-century French inventor of the earliest solar-powered engine, converting solar energy into mechanical steam power.

Augustin Mouchot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 April 1825 Semur-en-Auxois, France |

| Died | 4 October 1912 (aged 87) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Pioneering solar energy research |

| Awards | Gold Medal, Class 54, Paris World Exhibition (1878), Lauréat de l'Institut de France (1891, 1892) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics Physics |

| Institutions | Morvan 1845-49, Alençon 1853-62, Rennes and Tours 1864-71 |

| Influences | Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, Claude Pouillet |

Background

Mouchot was born in Semur-en-Auxois, France on 7 April 1825.[1] He first taught at the primary schools of Morvan (1845–1849) and later Dijon, before attaining a degree in Mathematics in 1852 and a Bachelor of Physical Sciences in 1853. Subsequently, he taught mathematics in the secondary schools of Alençon (1853–1862), Rennes and Lycée de Tours (1864–1871). It was during this period that he undertook research into solar energy, which led eventually to his obtaining government funding for full-time research.[2]

Solar research

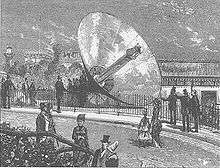

Mouchot was drawn to the idea of finding new alternative energy sources, believing that the coal which fueled the Industrial Revolution would eventually run out. In 1860 he began exploring solar cooking, drawing on the work of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure and Claude Pouillet. Further experiments involved a water-filled cauldron enclosed in glass, which would be exposed to the heat of the sun until the water boiled; the steam thus produced would provide motive power for a small steam engine. By August 1866, Mouchot had developed the first parabolic trough solar collector,[3] which was presented to the emperor Napoleon III in Paris. Mouchot continued development and increased the scale of his solar experiments. The publication of his book on solar energy, La Chaleur solaire et ses Applications industrielles ("Solar Heat and its Industrial Applications") (1869),[4] coincided with the unveiling of the largest solar steam engine he had yet built. This engine was displayed in Paris until the city fell under siege during the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, and was not found after the siege ended.

In 1861 M. Mouchot gave the name of Heliopompe to one of his invention, and in 1865 he had several small engines of this description at work at Tours, Indre-et-Loire[5]. Without discussing the question of priority with reference to Ericsson's invention, we may here remark that, as a distinction of construction, M. Mouchot has avoided the use of parabolic mirrors and added a glass jacket to retain the heat.

In September 1871, Mouchot received financial assistance from the General Council of Indre-et-Loire to install an experimental solar generator at the Tours library. He presented a paper on the generator to the Academy of Sciences on 4 October 1875, and in December of the same year he presented to the Academy a device he claimed would, in optimal sunshine, provide a steam flow of 140 liters per minute. Later the following year he sought permission from the ministry to take leave from his teaching position in order to develop an engine for the Universal Exhibition of 1878,[6] and in January 1877 obtained a mission and a grant for the purchase of materials and execution of his solar engines in French Algeria, where sunlight was in abundance. The director of science missions recommended Mouchot to the Governor of Algeria, stressing the importance of his mission to France, "for science and for the glory of the University".

Universal Exhibition, Paris 1878

Returning to metropolitan France in 1878, Mouchot and his assistant Abel Pifre displayed Mouchot's engine at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, and won a Gold Medal in Class 54 for his works, most notably the production of ice using concentrated solar heat. However, the continuing economic benefits of the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty, combined with a more efficient internal transportation for coal delivery, meant that coal became increasingly cheaper in France, reducing the necessity for research into alternative energy. The French government assessed in a report that solar energy was uneconomical, deeming Mouchot's research no longer important and ending his funding.

Mouchot subsequently went back to teaching. He was not completely forgotten however, and was named Lauréat de l'Institut by the Institut de France in 1891 and 1892, receiving prizes for work of the imagination. He died in 1912 in Paris.[1]

References

- "Augustin Bernard Mouchot", in Archives départementales, retrieved 22 January 2018

- Butti, Ken; Perlin, John (1980). A Golden Thread: 2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology. Cheshire Books. ISBN 0-442-24005-8.

- Gordon, Jeffrey, Solar energy, International Solar Energy Society, p.598 ISBN 978-1-902916-23-1

- Augustin Bernard Mouchot (1869) La Chaleur solaire et ses applications industrielles, Gauthier-Villars, Paris (Google eBook)

- "The Mouchot Solar Machine of 1865". hotairengines.org.

- Letter, 20 October 1876, the Minister of Education, National Archives File, Mission of Augustine Mouchot Algeria

Further reading

- Kryza, Frank T. (2003). The Power of Light. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-140021-4. This book describes Frank Shuman's solar project in Egypt and Mouchot's machine.

- Printing a Newspaper by Sun Power. (1883, January - June). Leslie’s Monthly Magazine, 15(1), 381–382.

External links

- Paul Collins, The Beautiful Possibility, Issue 6 Spring 2002

- Earth Portal Archives: Energy Quotes

- Larousse: Augustin Bernard Mouchot

- Augustin Mouchot

- La Chaleur Solaire

- Utilization of Solar Heat

- Solar Printer Mouchot 1882

- Call for research "Soleil Journal" newspaper printed in 1882

- SteamPunk Solar - Solar Heat and its Industrial Applications. An English translation of La Chaleur Solaire et ses Applications Industrielles