Asthall barrow

Asthall barrow is a high-status Anglo-Saxon burial mound from the seventh century AD. It is located in Asthall, Oxfordshire, and was excavated in 1923 and 1924.

.jpg)

Location

Asthall barrow is located along the strip of the A40 connecting the towns of Witney and Burford; it is immediately north of the A40 where it connects to Burford road, and just south of the byroad leading off Burford to Asthall and Swinbrook.[1][2] The barrow is prominently located, and gives its name to surrounding structures, such as Barrow Plaintation, Barrow Farmhouse, and Asthall Barrow Roundabout.[2] It overlooks the Thames Valley from Lechlade to Wytham Hill.[1] To the north it looks out at Leafield barrow; to the south appears Faringdon Hill and beyond it the Berkshire Downs at White Horse Hill, while to the southeast Sinodun Hill near Dorchester appears, with the Chilterns in the distance.[1]

Architecture

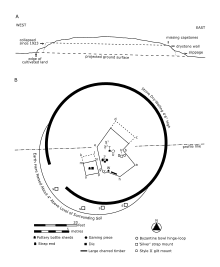

The barrow stands 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) high, and is about 55 ft (17 m) in diameter.[3] It was recorded as 8 ft 6 in (2.6 m) high around 1907,[4] but, in 1923, as 12 ft (3.7 m) high.[5] It is covered in trees, likely planted in the nineteenth century, and surrounded by a 4 ft 6 in (1.37 m) high dry stone retaining wall.[3][5] The presence of Romano–British grey wares in its soil, like the downward sloping surrounding land, suggests that it may have been constructed by scraping up the surrounding topsoil.[3] The land around the barrow is cultivated up to its edges; in 1992, it was planted with barley crops.[6]

Originally the barrow probably stood larger; in 1923 an elliptical section surrounding the southwest circumference was recorded as approximately 4 in (10 cm) higher than the field, suggesting that it was once a part of the barrow.[3][7] That the barrow's finds were not in the centre of its present dimensions also suggests that its original dimensions were somewhat different.[3] Slippage of the barrow's soil may also help explain the changed dimensions, and the recorded reduction in height over time.[3]

Excavation

The barrow was excavated in August 1923, and again in 1924, by George Bowles, the brother in law of the second Baron Redesdale, who owned the land.[8][9] Permission to excavate had been unsuccessfully sought in 1872, on behalf of George Rolleston.[10] The 1923 excavation was overseen by Bowles, although actually carried out by a Tom Arnold and five helpers.[11] Bowles was also aided by Edward Thurlow Leeds, then assistant keeper at the University of Oxford's Ashmolean Museum; Leeds offered suggestions, visited the site, and published the main discoveries.[8][9] He published the 1923 excavation along with an excavation plot by Bowls in The Antiquaries Journal in April 1924, and briefly discussed the 1924 excavation 15 years later in a chapter of A History of Oxfordshire.[12][13][9] Both excavations are also plotted, probably by Leeds, on a piece of blue linen held by the Ashmolean.[9]

Bowles dug an irregular, seven-cornered polygonal trench in 1923, and in 1924 added a rectangular trench to its side, along with four 18-inch-square trenches in the area of the raised surrounding soil.[3] He began by sinking a shaft 12 feet square and 12 feet deep; to this he added several subsequent extensions, each to the level of the field or below.[5][3] He labeled the corners A–H on his plot, omitting the F.[14][15] Bowles determined the barrow to be undisturbed and to consist of earth mixed with stones, along with the occasional sherd of Romano–British pottery.[5][3][note 1] The surface level was coated in yellowish clay, perhaps brought up from the River Windrush nearby.[18][19] This faded away toward corner B, Bowles noted, but was prevalent around corner G, the southern limit of the excavation.[20] Atop the clay Bowles found an abundance of charcoal and ashes, six inches thick in places (such as at point V on his plot), and forming only a thin covering elsewhere.[20][19] Bowles also recorded a large charred timber, between points G and H.[20][19]

The barrow contained a large assemblage of items, of a quality indicating the high-status nature of the burial.[21] There were at least seven vessels: three pottery, two hand-made jars, a Merovingian bottle, and a small silver bowl or cup.[17] Fragments of foil, five of which were stamped with zoomorphic interlace patterns, suggest the burial of a decorated drinking horn, and a pear-shaped mount was both patterned and gilded.[22] Other items appear to have been made of bone, and were likely pieces from a gaming set.[23] The finds were donated to the Ashmolean.[9]

Notes

- Bowles, whose daughter described him as a "gentleman amateur", may not be an authoritative voice for the idea that the barrow was hitherto intact.[16] Likewise, one of several explanations for the wide and seemingly random distribution of objects within is that the barrow had previously been opened.[17] Absent a re-excavation, Bowles's claim is thus uncertain.[16]

References

- Leeds 1924, p. 113.

- Historic England Asthall Barrow.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 98.

- Potts 1907, p. 345.

- Leeds 1924, p. 114.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 98–99.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 114–115.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 113–114.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 96.

- Leeds 1924, p. 114 n.2.

- Leeds 1924, p. 117.

- Leeds 1924.

- Leeds 1939.

- Leeds 1924, p. 115.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 98–00.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 96, 101.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 101.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 115–116.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 100.

- Leeds 1924, p. 116.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 112.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 103–104.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 105.

Bibliography

- "Asthall Barrow - an Anglo-Saxon Burial". Ashmolean Museum. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017.

- Dickinson, Tania M. & Speake, George (1992). "The Seventh-Century Cremation Burial in Asthall Barrow, Oxfordshire: A Reassessment" (PDF). In Carver, Martin (ed.). The Age of Sutton Hoo: The seventh century in north-western Europe. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 95–130. ISBN 0-85115-330-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Heritage at Risk 2018". Historic England. 8 November 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Historic England. "Asthall Barrow: an Anglo-Saxon burial mound 100m SSW of Barrow Farm (1008414)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Leeds, E. Thurlow (April 1924). "An Anglo-Saxon Cremation-burial of the Seventh Century in Asthall Barrow, Oxfordshire". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. IV (2): 113–126.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leeds, E. Thurlow (1939). "Anglo-Saxon Remains". In Salzman, Louis Francis (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. I. London: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. 346–372.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacGregor, Arthur & Bolick, Ellen (1993). "A Summary Catalogue of the Anglo-Saxon Collections (Non-Ferrous Metals)". British Archaeological Reports. 230. ISBN 978-0860547518.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manning, Percy (April 1898). "Notes on the Archæology of Oxford and its Neighbourhood". The Berks, Bucks & Oxon Archæological Journal. Berkshire Archaeological Society. 4 (1): 9–10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meaney, Audrey (1964). A Gazetteer of Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites. London: George Allen & Unwin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Potts, William (1907). "Ancient Earthworks". In Page, William (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. II. London: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. 303–349.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Timby, Jane (January 1993). A40 Witney Bypass to Sturt Farm Improvement: Archaeological Survey (PDF). Cirencester: Cotswold Archaeological Trust.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Windle, Bertram (July 1901). "A Tentative List of Objects of Prehistoric and Early Historic Interest in the Counties of Berks, Bucks and Oxford". The Berks, Bucks & Oxon Archæological Journal. Berkshire Archaeological Society. 7 (2): 43–47.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)