Assault on Nijmegen

The Assault on Nijmegen occurred on the night of 10 August 1589, involving troops of the mercenary Martin Schenck von Nydeggen against the small garrison and some citizens at the city of Nijmegen.

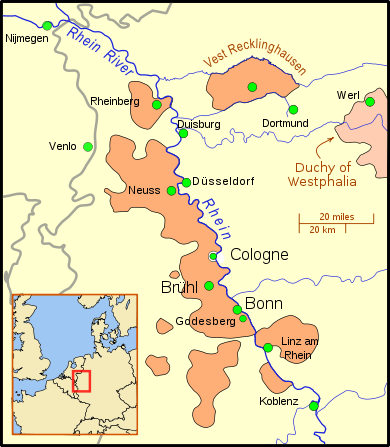

Located at the confluence of the Waal and Rhine rivers, Nijmegen was strategically important to the defense of the Dutch provinces and the Electorate of Cologne. Planning to take the city by surprise, Schenck and his troops would then reinforce the city, provision it and prepare it for siege by troops of Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma.

In the attack, Schenck and his soldiers tried to enter the city from barges on the Waal river. Some of the barges floated past the rendezvous point, and landed further down river. In the abortive battle, Schenck and many of his men drowned in the river. It was the second to last action of the Cologne War.

Context

The Cologne War was the first major test of the 1555 religious Peace of Augsburg's and the principle of ecclesiastical reservation. It was triggered by the 1582 conversion of the Archbishop-Prince Elector of Cologne, Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg, to Calvinism, his subsequent marriage to Agnes von Mansfeld-Eisleben in 1583, and his declaration of religious parity for Protestants and Catholics in the electorate. When Gebhard refused to relinquish the ecclesiastical see, the Cathedral chapter elected a competing archbishop, Ernst of Bavaria.[1]

For the first two years, the competing archbishops fought to a standstill. Both had external help: Ernst's oldest brother, Wilhelm V, Duke of Bavaria provided soldiers and funds, and his second eldest brother, Ferdinand, commanded the small army in his name, and Gebhard's brother, Karl Truchsess von Waldburg and several Protestant supporters within the Electorate provided both soldiers and funds. In the immediate months of the war's outbreak, the Oberstift campaign resulted in Gebhard's loss of several important cities and citadels, which eventually changed hands several times in the course of the war. In the 1585–86 campaigns, Dutch, Flemish, and English mercenaries had augmented his force, but he never attracted significant support from the other German princes, principally because he was a Calvinist and they were Lutherans. The Dutch had offered moderate help, recognizing the linkage between his cause and their own independence from Catholic Spain. Conversely, Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma and commander of Philip II of Spain's army in Flanders also recognized the linkage between Ernst's cause and his own. A series of Catholic bridgeheads on the Rhine would enable him to move his troops more easily around several of the strongholds opposing the re-establishment of Spanish control in the Netherlands. In 1585 and 1587, Ernst won several important victories, principally through the efforts of the Duke of Parma's army, and several of the German-Catholic counts, such as Karl von Mansfeld.[2]

By 1588, only Rheinberg remained outside the Spanish grasp, and in an effort to salvage a strategic major garrison in the electorate of Cologne for Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg, Martin Schenck intercepted and defeated seven companies of foot marching to Friesland, to reinforce Francisco Verdugo.[3]

Assault on Nijmegen

Despite the defeat of Verdugo, however, the rebellious Dutch provinces remained in jeopardy from Spain's Army of Flanders, which could attack from the relatively open border on the east. Holding Nijmegen, with its strategic access to the Waal and the Rhine rivers, would be a key point in securing the border between the Dutch provinces and Friesland. Strategically, it was important to seize, fortify, and provision the city, to prepare it for a potential Spanish siege.[4]

Plan

Martin Schenck devised a scheme through which he would take Nijmegen and enhance his own treasury. On the evening of 10 August 1589, Schenck and 20 barges of men—approximately 200 soldiers—made their way down the Waal to Nijmegen. Schenck's plan was to find a house with open windows and climb into the house using scaling hooks and ropes. Once the house was secured, they would quietly find the city gate, and open it to the rest of the force, which would be waiting on the river landing. They could then overpower the small local garrison and any citizens who felt resistance was necessary. Not only would they reinforce the city, but there would be opportunity for plunder as well.[5]

Plan goes awry

Schenck encountered several unforeseen problems. First, heavy summer rains had swelled the river well past the normal stage for August. The Waal was racing closer to its spring flood stage than the norm of late summer. Consequently, maneuvering the barges was far more difficult than Schenck anticipated. The barges that carried more than half his men were swept past both the chosen entry point and the landing point outside the city gate by a strong current.[6]

Second, everyone was awake at the house Schenck chose to enter. The owner was celebrating a wedding, and the house was filled with party-goers, many of whom were armed. Once the house's residents and their guests realized that strangers had made their way inside, they raised the alarm. The party-goers put up a stout defense. Schenck and his men were driven back through the house to their entry windows. One by one, they climbed back to the barges which, in the rough river, had drifted away from the walls, making it necessary for many of the men to swim. Many of the soldiers were swept away by the current and missed the barges.[6]

In the meantime, the men on the barges that had been pushed past the entry point by the river's current had struggled to bring them back to a landing. More citizens rushed out to defend the city against the new group of marauders. Schenck's force, divided and beset at all sides, was pushed back to the river. Several of the soldiers managed to push the barges into the river, and pull some of their comrades to safety, but it was difficult work: the darkness and the swiftness of the current made steadying the barges difficult, and the angry citizens of Nijmegen were firing arrows and small arms at the marauders. Eventually the soldiers forwent the ropes and scaling hooks, and simply jumped into the river, hoping to swim to the barges.[6]

In an effort to escape, Schenck jumped into the river but his heavy armor weighed him down, and, although he tried to swim to a nearby vessel. Most of the soldiers who could not get into a barge either drowned in the river or were pulled downstream; the few who did not drown were hunted down in the next couple of days and summarily executed. Schenck's body also was found a few days later; the body was decapitated, his head placed on a pike, and his body quartered. The pieces were exhibited at four gates.[7]

Consequences

Schenck was a known and feared mercenary who had shown little regard for the towns belonging to his friends, much less those of his enemies. His arrival to "reinforce" a local garrison was already a mixed blessing; although his military acumen had helped him accumulate multiple honors, his strategies were brutal and merciless, even in this age of warfare.[8] While his death was a military blow, it was a public relations blessing. In Westphalia, Neuss, Bonn, and Godesburg, Schenck had made himself and his men feared, and had done great damage to the personal appeal of the Calvinist Elector of Cologne's reputation and cause.[9]

Nijmegen was eventually captured by a Dutch and English force led by Maurice of Nassau on October 21 1591.

Footnotes

- Hajo Holborn, A History of Modern Germany, The Reformation. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959, pp. 252–256.

- Holborn, pp. 252–56; (in German) J. H. Hennes, Der Kampf um das Erzstift Koln, Cologne, 1878.

- Charles Maurice Davies, The History of Holland and the Dutch Republic, 1851, p. 233.

- Geoffrey Parker, The Flanders Army and the Spanish Road.Jonathan I. Israel, Conflict of Empires.

- Davies, p. 233; Schenck; Hennes, pp. 160-179.

- Hennes; Schenck, p. 179.

- Davies, p. 233.

- Jeremy Black, European warfare, 1494–1660, 2002. pp. 114–115; Edward Maslin Hulme, The Renaissance, 1915, p. 507–510; Schenck, p. 179.

- (in German) Leonard Ennen, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, v. 5, specifically p. 178; Hennes, pp. 156–158; Schenck, p. 179.