Arthur Callender

Arthur Robert Callender (13 December 1875 – 12 December 1936),[1] nicknamed 'Pecky', was an English engineer and archaeologist, best known for his role as assistant to Howard Carter during the excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb in the 1920s.

Arthur Robert Callender | |

|---|---|

Opening Tutankhamun's shrine. Callender is on the right of the photo | |

| Born | 13 December 1875 Skirbeck, near Boston, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 12 December 1936 (aged 60) Alexandria, Egypt |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Engineer and Egyptologist |

| Known for | Howard Carter's assistant when excavating Tutankhamun's tomb |

| Spouse(s) | Eliza Clara née Reynolds, (married 1901) |

Life

Callender was born in Skirbeck, near Boston, Lincolnshire, England, to engineer Robert Callender and Matilda (née Pepper). After training as an engineer he moved to Egypt and worked as a manager with the State Railways.[2] In 1911 he was awarded the Ottoman Order of the Medjidieh, fourth class, for his services as Assistant Inspector-General of the Auxiliary Railways of Upper Egypt.[3] He retired from the Railway Service in about 1920.[4]

Tutankhamun's tomb

During his time in Egypt, Callender took an interest in Egyptology and had been on friendly terms with archaeologist Howard Carter since the 1890s, when both were involved with the Egypt Exploration Fund.[5] In 1920, after retirement, Callender built a house at Armant, Egypt and joined a number of local excavations.[1] This was near the Valley of the Kings, where Carter was employed by Lord Carnarvon in a systematic search for any tombs missed by previous expeditions, in particular that of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun.[6] This search had yet to yield any significant results when, in October 1922, Carter began to excavate beneath the foundations of a row of ancient workman's huts in the heart of the valley. Deciding he would need a reliable assistant if a discovery was made, he visited Callender,[7] who agreed to join Carter's dig at short notice if required.[5] On 4 November Carter's team discovered a flight of steps which, once dug out, revealed a doorway sealed with ancient cartouches, suggesting an intact tomb. Carter ordered the staircase refilled, to await the arrival of his patron Lord Carnarvon, then in England.[6] Meanwhile, Carter contacted Callender, who joined the excavation on 10 November.[8]

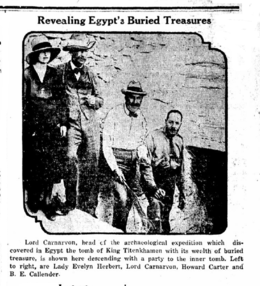

On 24 November 1922 Carnarvon, accompanied by his daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert, had arrived and were present when Carter and Callender supervised the uncovering of the stairway to the tomb, with a seal containing Tutankhamun's cartouche found on the doorway. This door was opened and the rubble filled corridor behind cleared, revealing the door to the main tomb.[9] On the 26 and 27 November Carter, Callender, Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn became the first people in modern times to enter the tomb.[10] Callender rigged up electric lighting, illuminating a large haul of items, as well as two more sealed doorways, including one to an inner burial chamber. A small hole was found in this doorway and Carter, Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn crawled through,[9] although Callender was too heavily built to do so.[11] Virtually intact, the tomb would ultimately be found to contain over 5,000 items.

The scale of the task of assessing and clearing the tomb was vast, with Carter obtaining the loan of experienced archaeologists, including Arthur Mace, Alfred Lucas and photographer Harry Burton.[12] Callender's role in the excavation however remained key. Described by one of Carter's biographers as "phlegmatic, unshakable, and remarkably versatile",[5] Callender was able to apply his engineer's experience to problems as they arose. He took charge when Carter was absent during the early days of the excavation,[13] when the risk of theft from the tomb was at its highest.[14] In December 1922, one visitor noted that, while a watchman's hut was being built, Callender stood guard outside the tomb "with a loaded rifle across his knee ... sitting in the gleaming hot sun ... with huge beads of perspiration upon his uncovered and balding head."[15] Once the excavation was fully underway, Callender's responsibilities included setting up the electrical installation for lighting the tomb[16] and organising the transport of materials from the rail station to the tomb site.[17] He also dismantled the shrine enclosing Tutankhamun's body, prepared other objects for removal,[4] and acted as interpreter for at least one meeting with the director general of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities, Pierre Lacau.[18]

There were clearly tensions in his working relationship with Carter, who noted in his journal on 25 January 1924: "Callender sent in his resignation – blaming my action towards him."[19] Callender however reconsidered, and was still working closely with Carter after December 1925,[20] and into 1926.[lower-alpha 1]

Callender also worked on other excavations, including assisting Walter Bryan Emery and Robert Mond in reconstructing the tomb of Ramose in 1924,[4] and explorations at Armant in 1935 and 1936.[21] Additionally, he sold artifacts including items to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Oriental Institute, Chicago.[1]

Personal life

On 14 August 1901 Callender married Eliza Clara Reynolds in Alexandria, Egypt.[1]

His death probably occurred on 12 December 1936 in Alexandria, aged 60,[1] [lower-alpha 2] although the death was never recorded by the Register Office in England, nor was it reported to the British Consulate in Egypt.[22] He died intestate.[23]

References

- Mention of Callender in Minnie Burton's diary confirms his presence in April 1926.

- Other sources indicate 1931[4] or 1937[22] as Callender's death year. The former cannot be correct as he was recorded as working after this.

- Griffith Institute website 2020, p. people: Arthur Robert Callender.

- Griffith Institute website 2020, p. People: Arthur Robert Callender.

- "No. 28469". The London Gazette. 4 February 1911. p. 1463.

- Dawson & Uphill 1972, p. 50.

- Winstone 2006, p. 141.

- Price 2007, pp. 119-128.

- Carter, p. 28 October 1922.

- Carter, p. 10 November 1922.

- Price 2007, pp. 121-122.

- Carter, p. 25-27 November 1922.

- Cross 2006, pp. 53-54.

- Ridley 2013, p. 124, Vol 99.

- Winstone 2006, p. 161.

- Cross 2006, p. 69.

- Breasted 1948, p. 316 et. seq.

- Carter, p. 27 November 1922; 1 November 1923.

- Carter, p. 3 November 1923.

- Carter, p. 13 December 1923.

- Carter, p. 25 January 1924.

- Winstone 2006, p. 287.

- "Armant 1935-36". Griffith Institute: excavations. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Winstone 2006, p. 324.

- Winstone 2006, p. 337.

Sources

- Breasted, Charles (1948). Pioneer of the Past. H. Jenkins. London. ISBN 1885923678.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carter, Howard. Excavation journals, 1922–1930. The Griffith Institute, Oxford.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cross, William (2006). Carnarvon, Carter and Tutankhamun Revisited: The Hidden Truths and Doomed Relationships. The author. ISBN 1-905914-36-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dawson, W; Uphill, E (1972). Who Was Who in Egyptology, 2nd edition. Egypt Exploration Society, London. ISBN 0856981257.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffith Institute website (2020). People: Arthur Robert Callender. The Griffith Institute, Oxford.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Price, Bill (2007). Tutankhamun, Egypt's Most Famous Pharaoh. Pocket Essentials, Hertfordshire. ISBN 1842432400.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ridley, Ronald T (2013). The Dean of Archaeological Photographers: Harry Burton Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 99, 2013. SAGE Publishing, California.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winstone, H.V.F. (2006). Howard Carter and the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. Barzan, Manchester. ISBN 1-905521-04-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)