Ars historica

Ars Historica was a genre of humanist historiography in the later Renaissance. It produced a small library of treatises underscoring the stylistic aspects of writing history as a work of art, but also introducing the contributions of philology and textual criticism in its precepts and evaluations.

Background

At the summit of his ars oratoria Cicero had celebrated history as the magistra vitae. In his De Oratore he proposed history as the summit of ars rhetorica, the rhetorical culture in which eloquence is at the service of the truth of human experience.

Within the context of the rhetorical culture of humanism, the ars historica was an attempt to introduce critical and scholarly criteria into historical literature. Its significance was great during the period of confessional struggle between Protestants and Catholics in the later sixteenth century. In addition to the examples of the classical historians (Herodotus and Thucydides, Livy and Tacitus), the contemporary works of Machiavelli and Guicciardini enhanced the prestige of historical writing. Two further Greek writers were classical sources for the ars historica: Lucian of Samosata and Dionysius of Halicarnassus.

Sixteenth century

The attempt to raise history to the status of a classical ars derived impetus from the mid-century critical renewal brought about by the Ars Poetica of Aristotle. The text of Aristotle's Poetics was an inspiration in Italy, renewing the critical discourse about literature. Francis Robortello, known as the father of hermeneutics and an Aristotelian exponent, also wrote the first treatise De arte historica in 1548.

Francesco Patrizi wrote ten dialogues on history in 1560. In 1566 Jean Bodin published his Methodus ad facilem historiarum cognitionem, a seminal work. Using the critical apparatus of humanist historiography Bodin reviews and evaluates the classical and contemporary bibliography of historical writing. The idea of method was also a leading systematic concept of the era, expanding the scope of the classical ars.[1] Bodin's Methodus reflects the search for new historical principles based on intellectual reform of textual criticism. Such an attempt speaks for the elevation of history as a pre-scientific organizing principle for the contemporary encyclopedia and its bibliography.

The vogue of the genre was international, stretching beyond the Italy of Robortello, Patrizi and their followers and the France of Bodin to the Basel humanists (Simon Grynaeus and Theodor Zwinger. Further it reached Protestant historians such David Chytraeus, Flanders (Francois Baudouin), Spain (Sebastian Fox Morcillo) and as far as England (Thomas Blundeville). In Basel Pietro Perna distinguished himself as a promoter of a new cultural and religious model rooted in Erasmian critical standards in religion and medicine but also in historical scholarship. As a historical printer he is best known for his illustrated editions of Paolo Giovio, but also for editions of standard and contemporary works, including Protestant chronicles and histories. Perna brought together all the major authors and works of the ars historica in two compilations. The Methodus historica (1576) featured Bodin followed by another dozen titles. The Artis Historicae Penus (1579) adds another five titles for a total of 18 works.

Subsequently, Perna's work served the Jesuit Antonio Possevino for his critique of Bodin [1592] and as the target and textual source for his Apparatus ad omnium gentium historiam (1597). It plagiarizes Bodin, but also updates his bibliography (Lipsius, Baronio, Carolus Sigonius, Tasso) and censures works on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

Seventeenth century

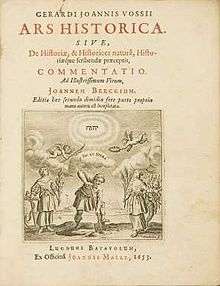

In the century that followed, interest in the rhetoric of the genre continued, though its intellectual content was exhausted. The literary focus of Agostino Mascardi's Dell’arte historica reflects the intellectual demotion of the magistra vitae concepts with the advent of Cartesian and scientific rationalism.[2] Gerardus Vossius published a work in 1623 by this title that had subsequent editions, including the one pictured above from 1653. Degory Wheare's Oxford contribution, De ratione et methodo legendi historias, also appeared in 1623.

Notes

- Neal W. Gilbert,(1960) Renaissance Concepts of Method, New York, Columbia UP.

- Girolamo Cotroneo (1971) I trattatisti dell'Ars Historica, Naples, Giannini.

References

- Peter G. Bietenholz, (1959) Der italienische Humanismus und die Blutezeit des Buchdrucks in Basel: die Basler Drucke italianischer Autoren von 1530 bis zum Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts, Basel-Stuttgart, Helbig & Lichtenhahn.

- Perini, Leandro, (2002) La vita e i tempi di Pietro Perna, Rome, Edizioni di storia, provides a numbered catalogue of the 430 editions printed by Perna between 1549 and 1582, including a library of historical works.

- Grafton, Anthony, (2007) What Was History? The art of history in early modern Europe, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, is a brilliant discussion of the Ars Historica tradition.