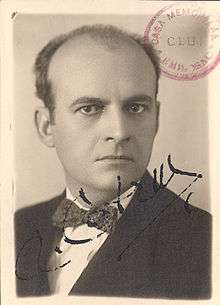

Aron Cotruș

Aron Cotruș (Romanian pronunciation: [aˈron koˈtruʃ]; 2 January 1891 – 1 November 1961) was a Romanian poet and diplomat who also supported the Iron Guard.

Life

He attended secondary school at Blaj, at the "Andrei Saguna" in Brasov and the Faculty of Letters in Vienna, and was part of the nationalist newspaper ""Românul" (Arad) and "Gazeta de Transilvania" (Brasov), but had and collaborations with cultural magazines "Gândirea", "Vremea", "Libertatea" (Orăștie), "Iconar" (Cernăuți) and others. Critic Al. T. Stamatiad described Cotruş as young Transylvania's "most talented poet".[1]

During World War I he was in Italy, where he worked under the Romanian Legation in Rome. After the war, in 1919, he returned to Romania, becoming a journalist in Arad. A royalist, he later became a supporter of Ion Antonescu. After the death of Queen Marie of Romania he wrote the important poem "Maria Doamna" ("Lady Marie"), in which, in the words of Lucian Boia, "the queen appears as a providential figure come from faroff shores to infuse the Romanian nation with a new force."[2]

He also became a member of the Romanian Writers' Society. He worked as a press attaché in Rome, Warsaw, and during the Second World War as a press secretary in Madrid and Lisbon. Along with Titus Vifor and Vintilă Horia he was assigned by the Iron Guard's "National Legionary State" to run the Romanian Propaganda Office in Rome, "The Fellowship of the Cross" .[3]

After the collapse of the Antonescu regime he became a political refugee in Franco's Spain and became the president of the exiled Romanian community, then editor of the pro-Guardist magazine "Carpathians", published in Madrid. In 1957 he settled in the United States at Long Beach, California, where he lived for the rest of his life. He died in La Mirada, California on November 1, 1961. His remains are in Holy Cross Cemetery, Cleveland, under a simple stone plaque.

Literature

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry describes him as a writer "whose messianic thunderings were couched in rolling free verse and a racy, sonorous vocabulary."[4] Along with Emil Isac, he opposed a neo-romantic and "prophetic" attitude borrowed from Octavian Goga.[5] In Cotruș's case, this took the form of an ethno-nationalist discourse about "the ethnic and social battles of the Romanians".[5]

Under Communism Cotrus was identified as a traitor, and as a representative of what Marxist critic Nestor Ignat called "hooliganism in literature".[6]

Publications

- "Poezii" ("Poems"). Orăștie, 1911

- "Sărbătoarea morții" ("Festival of Death"). Concordia, Arad, 1915. Edition II Bucharest, 1922

- "Neguri albe". ("white Neguri"). Alba-Iulia, 1920

- "România" ("Romania") (poem). Brasov, 1920. Edition II Arad, 1922

- "Versuri". ("Lyrics"). Library "sower", Arad, 1925

- "In robia lor" ("In their bondage"). Arad, 1926

- "Mâine". ("Tomorrow"). Publishing "Romanian Writing", Craiova, 1928. A second edition under the auspices of the "Societătii de Mâine" ("Society of Tomorrow"), Cluj, 1928

- "Holnap" (Tomorrow), Hungarian, published in Arad, 1929. Translated by Pal Bado

- "Strigăt pentru depărtări" ("Cry for the departed"). "ience", Timișoara, 1927

- "Printre oameni în mers". ("Some people walk"). Sosnowiec, Poland, 1933 (bibliographical rarity). Second edition of the Spanish translation of Gaetano Aparicio, Madrid 1945

- "Horia". Issue Get Warsaw, Poland, 1935. Edition II Brad 1936 (in just two years appear editions of volume 18. Only in appearing in Bucharest, during 1938: editions III, IV, V, VI). The Hungarian translation by A. Kibedi, Cluj, 1938

- "Versek" (book of poems in lb. Hungarian). Cluj, in 1935 (many of the poet's verses were published in the Saxon magazine "Klingsor" in Brasov, some translated by Alfred Margul-Sperber. Similarly, Zoltan Franyo translated some poems in German publishing them in magazines literature for the German community in Romania)

- "Culegere de versuri" ("Collection of poems"). Polish translation by Wladimir Lewice. Lvov, 1936

- "Tara" ("Country"). Bucharest, 1937. Edition II Lisbon, 1940

- "Miners", Bucharest, 1937

- "Peste prăpastii de potrivnicie" ("Over the precipice of misfortune"), Bucharest, 1938. Edition II Aparicio Gaetano Spanish translation, Madrid 1941

- "Maria Doamna" ("Lady Marie") (poem). Typography "Star", Bucharest, 1938 (deluxe edition)

- "Aron Cotruş: Lady Marie". Reviews published in literary magazines in the country at that time, collected and published as a homage to the poet, Bucharest, 1939

- "Rapsodie Valahă" ("Valah Rhapsody"). Madrid, 1940. Edition II Bucharest: "Star", 1941. Edition III of Madrid, Ed "Carpathians", 1954. Appeared in Spanish translation, Madrid, 1941 (Aparicio Gaetano's translation)

- "Rapsodie Dacă" ("If Rhapsody"). Publishing "Royal Foundations", Bucharest, 1942

- "Poema de Montserrat" (in "Escorial"), Spain, 1949; Second edition of Madrid, 1951

- "Poemas". Madrid 1951

- "Roads by storm." Madrid 1951

- "Canto Ramon Llull." Mallorca, Spain, 1952

- "Rhapsody Iberian". Publishing "Carpathians", Madrid, 1954

- "Between the Volga and Mississippi". "Carpathians", Madrid, 1956

- "Aron Cotruş – Complete Works". Editura "Dacia", Madrid, 1978 (edition îngrijitǎ Nicolae Roșca)

References

- (in Romanian) Ion Mierluțiu, "Un 'cvartet' modernist la Arad, în perioada interbelică" Archived March 30, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, in Revista Arca, Nr. 7-8-9/2010

- Lucian Boia, History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness, Central European University Press, Budapest, 2001 p.209

- (in Italian) Carmen Burcea, "L'immagine della Romania sulla stampa del Ventennio (II)" Archived 2018-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, in The Romanian Review of Political Sciences and International Relations, No. 2/2010, p.31

- Roland Greene, et al, The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ., 2012, p.1206.

- John Neubauer, Marcel Cornis-Pope, Sándor Kibédi Varga, Nicolae Harsanyi, "Transylvania's Literary Cultures: Rivalry and Interaction", in Marcel Cornis-Pope, John Neubauer (eds.), History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe, Vol. 2, John Benjamins, Amsterdam & Philadelphia, 2004, p.264

- Nestor Ignat – Cu privire la valorificarea moştenirii culturale.