Army Printing and Stationery Service

The Army Printing and Stationery Service was a British Army unit of the First World War and the early interwar period. It had its origins in the Base Stationery Depot, a small unit sent with the British Expeditionary Force to distribute stationery. During the course of the war it grew to a battalion-sized unit and produced and printed its own publications. The unit ran three printing presses in France and at one point had 13 stations across Europe and the Middle East. The unit was responsible for printing and distributing documents ranging from the simple field service postcard issued regularly to every man in the British Army to highly specialised manuals. By the war's end it was distributing up to 400,000 packages of documents per week.

| Army Printing and Stationery Service | |

|---|---|

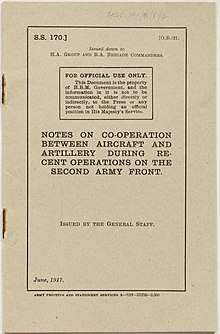

Front cover of a 1917 document produced by the Army Printing and Stationery Service | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Allegiance | British Empire |

| Branch | Army |

| Type | Stationery production and distribution |

| Role | Support |

| Size | Approx 900 men maximum |

| Engagements | First World War |

Base Stationery Depot

The need for a stationery distribution unit had been identified in the British Army's mobilisation plan of January 1912.[1] This unit, was known as the Base Stationery Depot and was an offshoot of the War Office's secretary's department.[2] It came under the jurisdiction of the Inspectorate of Communications.[1] The unit mobilised on 13 August 1914 and soon after accompanied the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to France.[1][2][3][4] This unit was commanded by Captain S G Partridge, a former War Office clerk of eight years service, who was assisted by two lieutenants – also former clerks.[1][3] Partridge commanded a sergeant and six privates who had previously been expert packers at Her Majesty's Stationery Office. The unit's original remit was merely to arrange the distribution of existing publications to units of the BEF in the field.[3]

The depot had a difficult start, being responsible for the management of large volumes of stationery arriving at the channel ports which were being overrun by German advances. The depot was withdrawn as far back as Nantes in western France before the Western Front stabilised and it was brought forwards to Abbeville (via temporary locations at Le Havre and Rouen). In the confusion a number of shipments were mislaid including a batch of valuable typewriters, which particularly vexed Partridge.[1]

Army Printing and Stationery Service

The Base Stationery Depot's remit soon expanded and it was charged with arranging the printing and distribution of its own material. As such the unit was renamed the Army Printing and Stationery Service. By the end of its first year the unit, still commanded by Partridge, had expanded to 20 officers and 176 men. By the end of 1915 it numbered 17 officers and 400 men and in 1917 had reached battalion size – some 53 officers and 850 men.[5] The majority of the unit's men worked in the printing and photography company, which in 1919 came under the command of Major George Bourne, a former print works manager.[3][6]

By the war's end Partridge had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel and appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his service; in 1919 he was promoted to colonel and appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George.[7][8] At the unit's height Partridge, as director, was assisted by a number of deputy directors and assistant directors ranking as lieutenant-colonels and deputy assistant directors ranking as majors.[9][10]

The Army Printing and Stationery Service initially relied on old linotype machines inherited from the Royal Engineers but established its first dedicated modern press at Le Havre in July 1915. This first press became known as Press C; Press A was set-up at Boulogne in January 1916 and Press B was in Abbeville. The unit also had contracts with 20 printing firms in the United Kingdom to meet periods of increased demand.[3] The unit was also responsible for the issue and maintenance of around 5,000 typewriters used by field units and maintained a team of mobile motorcycle-mounted mechanics to carry out repairs to them.[11][12] The service had branches in many of the theatres that the British Army operated in during the war including Italy, Greece, Palestine, Egypt, Malta and Mesopotamia.[3] By 1917 it maintained 13 separate stations across all fronts.[5]

The unit is recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission as having suffered just one death relating to its service – that of Lieutenant Charles Mackenzie Thomson who died on 24 March 1919 at the age of 44.[13] A similar unit, the Indian Government Stationery Department, operated for Indian forces of the war.[14] The British unit as well as an Australian Army Printing and Stationery Service also served in the Second World War.[15][16]

Publications

Initially the unit was purely responsive, supplying only that material that had been requested by individual British Army units in the field. In the winter of 1914–15 only 103 copies of a manual on the prevention of frost bite were requested from a print run of 250,000, during a period in which 20,000 men were hospitalised with the injury.[3] Another incident saw a print run of 250,000 aircraft recognition cards – originally intended to be issued to every British soldier – reduced to just 50,000 by the Adjutant General. The run was increased to 200,000 days later by the War Office, leading to considerable confusion and inefficiency.[17] Following these incidents the service became responsible for specifying the amount of manuals each unit would receive and supplying the same.[3]

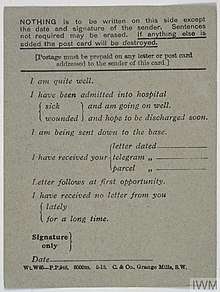

The unit also issued standard British Army forms and documents and printed in English, Flemish, French, Chinese and various Indian languages.[3][4] Some documents had a very wide distribution and huge production runs were necessary – such as for the field service postcards that were regularly issued to every man in the British and Indian Armies – while some manuals were highly specialised and print runs of only 500 were made.[12][11] Partridge's unit also undertook the printing of mess menus and Christmas cards.[17] The Army Printing and Stationery Service was also responsible for the manufacture and issuing of the rubber stamps used by mail censors.[11] From 1916 all documents produced by the unit were denoted with a SS (Stationery Service) reference code.[11] During a paper shortage in 1918 Partridge implemented a large scale paper recycling campaign.[17]

Many new documents were produced during the course of the war, averaging one every two days. By the end of the war the unit maintained stock of 1,100 separate documents and was distributing almost 400,000 packages per week.[12] Documents classified as secret – such as the BEF orders of battle – were produced at night under direct supervision of an officer and with labour divided such that no one person had possession of the whole document.[3][17] The unit was capable of turning out new documents very quickly. On one occasion, in April 1915, the unit completed a print run of 15,000 instructions for the firing of rifle grenades that were ready the morning after receiving the text at 5.30pm.[12]

References

- Griffith, Paddy (1996). Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army's Art of Attack, 1916–18. Yale University Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780300066630. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Great Britain War Office (1992). Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War, 1914–1920. London Stamp Exchange. p. 200. ISBN 9780948130144. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Bull, Stephen (2014). An Officer's Manual of the Western Front: 1914-1918. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 9781844862436.

- Cordery, Bob (2014). Brothers in Arms and Brothers in the Lodge. p. 31. ISBN 9781291989557. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Barty-King, Hugh (1986). Her Majesty's Stationery Office: the story of the first 200 years, 1786–1986. H.M.S.O. p. 57. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "No. 31631". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 November 1919. p. 13534.

- "No. 30576". The London Gazette (Supplement). 12 March 1918. p. 3289.

- "No. 31684". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 December 1919. p. 15436.

- "No. 30794". The London Gazette (Supplement). 12 July 1918. p. 8265.

- "No. 31148". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 January 1919. p. 1435.

- Griffith, Paddy (1996). Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army's Art of Attack, 1916–18. Yale University Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780300066630. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Bull, Stephen (2014). An Officer's Manual of the Western Front: 1914-1918. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 9781844862436.

- "Results – Regiment: Army Printing and Stationery Services". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Results – Regiment: Indian Government Stationery Department". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Results – Regiment: Australian Army Printing and Stationery Service". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Report on the Army Printing and Stationery Service, 1939–1945". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Griffith, Paddy (1996). Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army's Art of Attack, 1916–18. Yale University Press. p. 182. ISBN 9780300066630. Retrieved 21 February 2019.