Arithmaurel

The Arithmaurel was a mechanical calculator that had a very intuitive user interface, especially for multiplying and dividing numbers because the result was displayed as soon as the operands were entered. It was first patented in France by Timoleon Maurel, in 1842.[1] It received a gold medal at the French national show in Paris in 1849.[2] Unfortunately its complexity and the fragility of its design prevented it from being manufactured.[3]

Its name came from the concatenation of Arithmometer, the machine that inspired its design and of Maurel, the name of its inventor. The heart of the machine uses one Leibniz stepped cylinder driven by a set of differential gears.[4]

History

Timoleon Maurel patented an early version of his machine in 1842,[1] he then improved its design with the help of Jean Jayet and patented it in 1846.[5] This is the design that won a gold medal at the Exposition nationale de Paris in 1849.

Winnerl, a French clockmaker, was asked to manufacture the device in 1850, but only thirty machines were built because the machine was too complex for the manufacturing capabilities of the time.[6] During the first four years, Winnerl was not able to build any of the 8 digit machines (a minimum for any professional usage) that had been ordered while Thomas de Colmar delivered, during the same period, two hundred 10 digit Arithmometers and fifty 16 digit ones.[7]

None of the machines that were built and none of the machines described in the patents could be used at full capacity because the capacity of the result display register was equal to the capacity of the operand register (for a multiplication, the capacity of the result register should be equal to the capacity of the operand register augmented by the capacity of the operator register).

Description

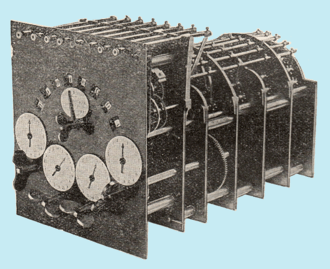

Following is a description of one of the two machines introduced in the 1846 patent.[5] It has a capacity of five digits for the operator and ten digits for the operand and the result registers.

All the registers are located on the front panel, the reset mechanism is on the side.

- 10 numbered stems, arranged horizontally at the top of the front panel, can be pulled at different lengths to enter the operands with the rightmost stem representing units.

- A 10 digit display register located in the middle is used to display the results.

- 5 dials, each coupled with an input key, are used to enter the operators with the rightmost dial representing units. Turning the units key one division clockwise will add the content of the operand register to the total. Turning the units key one division counterclockwise will subtract the content of the operand register from the current total. Turning the tens key one division clockwise will add 10 times the content of the operand register to the total etc..

Notes

- (fr)1842 patent - Document scanned by www.ami19.org

- (fr) Rapport du jury central sur les produits de l'agriculture et de l'industrie exposés en 1849, Tome II, page 542 - 548, Imprimerie Nationale, 1850 Gallica

- (fr) Le calcul simplifié Maurice d'Ocagne, page 269, Bibliothèque numérique du CNAM

- (fr) Philbert Maurice d'Ocagne (fr), Le Calcul Simplifié, Gauthier-Villars et Fils, 1894, page 29

- (fr) patent held by Maurel and Jayet 1846 - Document scanned par www.ami19.org

- (fr) Jean Marguin, Histoire des instruments et machines à calculer, Hermann, 1994, page 130

- (fr) Cosmos, Janvier 1854, page 77 Document scanned by Valéry Monnier

References

- (fr) Jacques Boyer, Les machines à calculer et leur utilisation pratique, La Science et la Vie, page 345-356, N⁰ 34, septembre 1917

- (fr) René Taton, Le calcul mécanique, Collection Que sais-je, Presses Universitaires de France, 1949

External links

- ami19.org - Site for patents and articles on 19th century mechanical calculators

- (fr) Museum of the arts et métiers