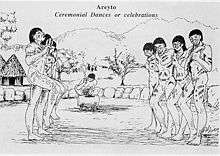

Areíto

The areíto or areyto was a Taíno language word adopted by the Spanish colonizers to describe a type of religious song and dance performed by the Taíno people of the Caribbean. The areíto was a ceremonial act that was believed to narrate and honor the heroic deeds of Taíno ancestors, chiefs, gods, and cemis. Areítos involved lyrics and choreography and were often accompanied by varied instrumentation. They were performed in the central plazas of the villages and were attended by the local community members as well as members of neighboring communities.[1][2][3]

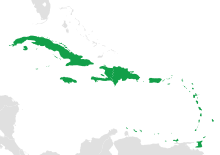

Taíno people & culture

Artifactual evidence in the Greater and Lesser Antilles indicates the presence of humans for at least 5,000 years prior to Columbus' arrival. Taíno culture emerged on the islands of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico and likely descended from an intermingling of the Arawak peoples from South America and the archaic peoples who migrated from Mesoamerica and Florida.[1]

Agriculture & lifestyle

The Taíno were agricultural, with their primary crop being the cassava. The cassava was poisonous if ingested raw, and had to be prepared using a special cooking process. There were many seasonal rituals created around its growing season. The Taíno were believed to eat a lot of fish. Colonizers noted fishing methods that involved a poisoning the fish so that they would die and float on top of the water and then collecting them for consumption. This poison did not affect the consumer.[1]

Social structure & ceremonies

The Taíno lived in communities governed by leaders called caciques. Archeological evidence suggests a class structure in which the higher class nitaínos (chiefs, warriors, artists) were believed to have power over the lower class naborias. The cacique was responsible for organizing areitos, which sometimes involved the whole community, with men and women combined, or sometimes just included men or women. Areítos were held in designated spaces, specifically the public plaza or dance ground outside the chief's house. Taíno villages often featured an elaborate dance court: an outdoor area surrounded by earthwork banks and sometimes stone carvings of cemis. These ceremonies occurred at times of importance such as marriage, death, after a disaster, or to give thanks to the gods and ancestors.[1][5][6]

Art & ceremonial objects

_(14783570345).jpg)

The Taíno had no written language but produced ornate sculptures from stone, wood, and clay that were used in many types of ceremony. Those that resembled gods were called cemis or zemis. They also created many other sacred objects including stone collars, ceremonial seats and axes, and varying types of amulet.[1]

Cemis & belief systems

Cemi is a Taíno word for god, as well as a word that described the sacred objects that represented and embodied gods. These same objects also represented ancestors and were believed to have supernatural powers. Each member of a given Taíno community was in possession of one or more cemis, which connoted both political and social as well as spiritual power. They were kept in shrines, and sometimes traded or given as gifts. The caciques were in possession of the most powerful cemis, and sometimes their skulls were preserved and turned into cemis as part of their burial ceremonies. Cemis played an important role in decision making, and caciques sought guidance from cemis when planning one of the first major rebellions against Spanish oppression. Their precise role in areíto ceremony is unknown, although it was observed by the colonizers that the cemis were often present during performances.[1][3]

Varying accounts of Areíto from colonists

Most of our information about areíto comes from the writings of Spanish colonizers. There are several primary accounts describing areíto in the Antilles from the period of early contact. Each account characterizes areíto slightly differently, leading to the terms broad, all encompassing nature. Areíto was a Taíno word that the Spanish adopted to describe epic poems, song-dances, ceremonies, festivals, performances, and ritual.[9]

Ramon Pane

Ramón Pane, a missionary who arrived in the new world in 1494, chronicled events in which the Taíno participated in singing and recitations of epic 'poems' and 'ancient texts' that they 'learnt by heart' accompanied by percussive instruments that looked like gourds. Pané drew comparisons between these Taíno performances and ceremonies of the Moors, additionally observing that areíto served as a mnemonic device for societal rules and traditions.[9][10]

Peter Martyr

Peter Martyr, a royal chronicler writing in the early 1500s who never traveled to the new world but instead gleaned information from discussions with other travelers, focused on areíto's function as a historiographical method. His accounts detail areíto's role in commemorating the great deeds of ancestors in peace, war, and love. He noted how the content of the narrative affected the style of its delivery and emphasized the role of the cacique and his immediate family in the tradition of learning and performing areíto.[9]

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés served as royal chronicler after Martyr, and traveled to the new world numerous times, observing what he deemed areítos in the Antilles as well as in Nicaragua. Although Oviedo was aware of the distinction between the customs of indigenous peoples of Nicaragua and the Antillles and although he learned a separate word for these differing performance practices, he used the term areíto to encompass their performances. Oviedo also honed in on the integral role of dance and movement in the areíto of the Taíno. Shifting the descriptions of these ceremonies away from 'poem' and towards 'song-dances' Oviedo noted that the songs were accompanied by precise and complex choreography and lead by a 'dance-master' who could be either male or female. He observed that they were performed by large groups of people, and that there was often a call and response of sound and movement between the leader and the group. Additionally, he distinguished between two types of areíto, one which commemorated historical events and the other which served as entertainment for festivals.[9][11]

Bartolomé de las Casas

.jpg)

Bartolomé de las Casas traveled to the new world as a colonist, but once there began writing in defense of the indigenous peoples. He described dancing accompanied by wooden drums and flutes. He noted that they would sometimes form lines with their hands on each other's shoulders and dance like that. He also described scenes of the women preparing food while singing as a group, using areíto as the word for their songs. His definition of areíto was even more inclusive than Oviedo, including many elements of festivals such as drinking, feasting, celebration, and pantomime. Later colonizers also adopted the term areíto to describe songs, dances, performances, festivals, and ceremonies that they encountered in other diverse parts of the new world. A common thread through many historical accounts is that the content of the song or poem or the intention of the ceremony or festival was observed to focus on the remembering, honoring, and telling of historical deeds.[9][10][11]

Examples

.jpg)

Several specific accounts of areíto recorded by chroniclers of the new world illuminate how song and dance were used as ritual, storytelling, historiography, celebration, and in exchanges of power and resources.

Anacaona

The female cacique Anacaona, was one of the early noted composers of areítos. According to Las Casas, Bartholomew Columbus (Christopher's brother) was exploring the island when he met with Anacoana's brother, Bohechío. After negotiating a trade between the colonizers and his people, Bohechío honored the Christians with an areíto in which his thirty wives danced and sang wearing white loincloths, and completed the areíto by kneeling in front of the men. In an alternate account of this same event by Oviedo, Anacaona gathered a group of three hundred virgins to dance for Bartholomew before her brother made the trade, using the areíto to aid in negotiation. After the dance, she invited the colonizers to a feast.[9][10][14]

Guarionex

In an account by Las Casas, the cacique Guarionex gave his areíto to Mayobanex, a neighboring cacique, in exchange for military protection. Guarionex taught the lyrics and the dance choreography to Mayobanex, connecting them to each other and to the history, mythology, and power of Guarionex's ancestry. Even though both caciques understood that there was great risk of defeat in the upcoming attack of the Spanish, Mayobanex agreed to defend Guaironex and his people to honor the pact they had made in the sharing of the areíto.[9]

Hatuey

Hatuey, a cacique who had fled the Spaniards but knew of an impending attack, gathered his people together and told them that one of the reasons why the Spanish killed them was because they worship the god of gold. He believed that if he and his people performed an areíto for the god of gold, a basket of gold in their possession, that perhaps the god of gold would be pleased and tell the colonizers not to harm Hatuey and his people.[10]

Musical props

Music played an integral role in areíto. Colonial observations note the use of various instruments in the dances, performances, and ceremonies including rattles made from wood or gourds filled with stones, bone whistles and flutes, horns and made out of large sea shells, and drums made from hollowed out logs. Oftentimes, instruments were secured to the body so as to respond sonically to the movements of the body.[1][14]

See also

References

- Bercht, Fatima; Brodsky, Estrellita (1997). Taíno: Pre-Columbian Art and Culture from the Caribbean. New York, NY: The Monacelli Press. p. 21.

- Taylor, Diana (2003). The Archive and The Repertoire. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 15.

- Oliver, José R. (2009). Caciques and Cemí Idols: The Web Spun by Taíno Rulers Between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 103–4, 107–8, 114–115.

- Kikos. "WikiCommons".

- Coopersmith, Jacob Maurice (1945). "Music and Musicians of the Dominican Republic: A Survey--Part I". The Musical Quarterly. 31 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1093/mq/xxxi.1.71. JSTOR 739339.

- Saunders, Nicholas J. (2005). The Peoples of the Caribbean: An Encyclopedia of Archeology and Traditional Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 16. ISBN 1576077012. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Smithsonian Institution. Board of Regents. (1846). Annual report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Public Domain. Found on wiki commons. Uploaded from Government Museum of Tibes.

- Scolieri, P. A. (2013). Dancing the New World: Aztecs, Spaniards, and the Choreography of Conquest. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 24–44.

- Thompson, Donald (1993). "The "Cronistas de Indias" Revisited: Historical Reports, Archeological Evidence, and Literary and Artistic Traces of Indigenous Music and Dance in the Greater Antilles at the Time of the "Conquista"". Latin American Music Review. 14 (2): 181–201. doi:10.2307/780174. JSTOR 780174. S2CID 192194451.

- Simmons, Merle L. (1960). "Pre-Conquest Narrative Songs in Spanish America". The Journal of American Folklore. 73 (288): 103–111. doi:10.2307/537891. JSTOR 537891.

- Serrato, Francisco (1893). Cristóbal Colón: Historia del Descubrimiento de América. Madrid: El Progreso Editorial.

- "Prisión de la reina Anacaona". Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla.

- Dale Olsen, Daniel Sheehy Handbook of Latin American Music, Second Edition 2007- Page 164 "From the descriptions of Arawak musical activities in the writings of the Spanish chroniclers (Cárdenas 1981; Casas 1965; López de Gómara 1965; Pané 1974), we learn that the areyto (also areito)—a celebration that combined poetry, songs.

External links

- Centro Ceremonial Indígena de Tibes Tibes is an archeological site in the Caribbean which has provided a wealth of evidence about indigenous cultures of the region.

- Taino: BBC Spirit of the Jaguar, Hunters of the Caribbean Sea This is a BBC documentary on Taíno culture and lifestyle through an undeniably Western lens.