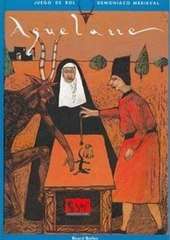

Aquelarre (role-playing game)

Aquelarre is a medieval demoniacal fantasy role-playing game created by Ricard Ibáñez and released by Barcelona publisher Joc Internacional (International Games) in 1990. It was the first role-playing game completely conceived and created in Spain.

Description

Although Joc Internacional had previously produced Spanish translations of popular North American and British role-playing products, Aquelarre was the first role-playing game to be entirely designed and published in Spain.[1]

Aquelarre is set in the Iberian Peninsula during the 13th and 14th centuries of the Middle Ages.[2] Players take on the roles of normal humans who walk a fine line between living ordinary and legal lives of drudgery, or using forbidden magic to lift themselves out of squalor. Almost half of the book is dedicated to demons and magic.[3]

The setting includes several feuding kingdoms (Castile, Aragon, Portugal, Navarra and Granada). Players not only have to deal with resultant wars, but also the hunger and disease that was endemic to the rigid feudal system.

Gameplay

Aquelarre uses a variant of Chaosium's Basic Role-Playing system developed for RuneQuest.

Character generation

Each player chooses a class for the character. Each class provides access to a number of skills. Abilities are determined randomly, and skill levels are then extropolated from the relevant abilities.[3]

Task resolution

In order to succeed at a task, the player must roll percentile dice equal to or lower than the character's relevant skill level (to which the referee may have added situational modifiers.)[3]

Combat

One round of combat takes 12 seconds of game time, during which time each character can perform two actions, choosing from Move, Attack and Defend.[3]

Armor has two ratings: how much damage a weapon has to do to pierce it in one strike, and how much damage the armor can take overall before it is effectively ruined.[3]

Magic

Although magic is useful and can help the characters to resolve tasks which have been set before them, most other people see magic as evil and demonic. This tension between the characters' use of magic and the commonly held perceptiuon of magic forms the centrepiece of this game.[3] The magic system is complex, and unlike many other role-playing games, successful spell completion is difficult to accomplish. Characters must also learn to practice the arcane arts in private, lest they come to the attention of the secretive Fraternitas Vera Lucis (in this role-playing universe, the antecedent of the Inquisition). The penalty for being discovered using magic is immediate death.

Publication history

- 1990–1998: Joc International published the first edition rulebook as well as a referee's screen, a bestiary, adventures, a supplement about Catalonia, and a supplement that extended play into Madrid during the 16th-century Renaissance.

- 1999–2002 : La Caja de Pandora published a second edition, as well as new supplements about play in Navarra and Galicia.

- 2002–2004: Editorial Projects Crom published new supplements focussed on specific professions (doctors, inquisitors, alchemists), as well as the kingdom of Granada. They also published a number of new adventures, and re-issued previously published supplements.

- 2011: Nosolorol Ediciones published the third edition of Aquelarre.

Manuals and supplements

First edition, Joc Internacional

- Aquelarre (1990)

- Lilith (1991)

- Demon Rerum (1992)

- Danza Macabra (1992, reissued by Editorial Crom Projects in 2002)

- Rinascita (1993)

- Dragons (1994)

- Rincon (1995)

- 'Villa y Corte' '(1996)

Second edition, La Caja de Pandora

- Aquelarre (1999)

- Myths and Legends Vol.0 + Screens (2000)

- Myths and Legends Vol.I Ad Intra Mare I (2000)

- Myths and Legends Vol. II Ad Intra Mare II (2000)

- Myths and Legends Vol. III Ultreya (2000)

- Aker Codex: Breogan's Home (2000)

- Aker Codex: Gentleman's Land (2000)

- Akercodex, the legends of the goat (2000)

- Aquelarre, the temptation (2001)

- The Court of the Holy Inquisition (Codex Inquisoturius) (2001)

Second edition, Editorial Projects Crom

- Codex Inquisistorius. The Court of the Holy Inquisition (2002)

- La Fraternitas de la Vera Lucis (2002)

- The Macabre Dance and other stories ... + Screens (2002)

- Al Andalus <ref> IBÁÑEZ ORTÍ Ricard, Al-Andalus , (2002)

- Medina Garnatha (2002)

- Jentilen Lurra (2002)

- Ars Medica (2002)

- Grimorio (2002)

- The misty north: Jentilen Lurra (2002)

- The foggy north: Fogar de Breogan (2002)

- Sefarad <ref> (2003)

- Apolarre Apocrypha (2003)

- Ars Carmina, the secret book of minstrels (2003)

- Ars Magna, the secret book of the alchemists (2003)

- Descripio Cordubae (2003)

- Aquelarre, la tentation (French edition of the basic rules, 2003)

- Danse macabre (French translation of the referee's screen and the supplement, 2004)

Third edition, Nosorols Ediciones

- Aquelarre (2011)

- Asturies Medievalia (2012)

- Saeptum Arbitri (2012)

- Aquelarre: Breviarium (2013)

- Ars Malefica (2013)

- Legendarium Inferni (2014)

- Daemonolatreia (2015)

- Bestiarium Hispaniae (2015)

- Decameron (2016)

- Return to Rincon (2017)

- Ex Mundo tenebrarum (2018)

English edition, Nocturnal Media

- Aquelarre (2018)

- Aquelarre Brevarium (2018)

- Asturies Medievalia (2018)

- Fatum Sperantia (2018)

Reception

Lester Smith was asked by an American publisher to evaluate whether Aquelarre was suitable for an American audience. Smith replied that it was not, and in the October 1992 edition of Dragon (Issue #186), he explained his reasons why. First, Smith felt the American public was not ready for a game where the Spanish title translates as a ceremony for calling up major demons. Secondly, he felt "another stumbling block for American publishers, in regards to the art, is occasional full frontal nudity, both female and male." Thirdly, he felt the American public was not ready for a game where almost half of the book was dedicated to explicitly worded magical spells such as "Sexual Attraction" and demon summoning. Smith did concede that the book itself had "a nice appearance", and the "text is laid out in easy-to-read fashion." He found the "tone of the text is a personable one", and called the book overall "a nice package." He also found the game system "smoothly executed", with "a lot of solid background material" and four sample adventures. Overall, Smith wanted to like Aquellare, but found the product too raw and realistic for his American tastes.[3]

External links

- The official website of Ricard Ibáñez Histo-Rol,

- Fanzine dedicated to the game Dramatis Personae,

References

- IBÁÑEZ, Ricard (1990). "Aquelarre, demonic-medieval role-playing game". Barcelona: "Joc Internacional". ISBN 84-7831-038-X.

- "Aquelarre - RPGnet RPG Game Index". index.rpg.net. Retrieved Oct 29, 2019.

- Smith, Lester (October 1992). "Roleplaying Reviews". Dragon. TSR, Inc. (186): 36–38.