Aqua Tofana

Aqua Tofana (also known as Acqua Toffana, Acquetta Perugina, and Aqua Tufania and Manna di San Nicola) was a strong poison that was reputedly widely used in Naples, Perugia, and Rome, Italy. During the early 17th century Giulia Tofana, or Tofania, an infamous woman from Palermo, made a good business for over fifty years selling her large production (she employed her daughter and several other helpers) of Aqua Tofana to would-be widows.

Original creation

The first recorded mention of Acqua Tofana (literally meaning "Tofana water") is from 1632–33.[1]

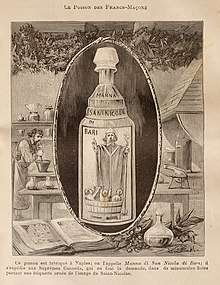

Perhaps an older recipe had been refined by Tofana and her daughter, Girolama Spera, around 1650 in Rome. The 'tradename' "Manna di San Nicola", i.e. "Manna of St. Nicholas of Bari" might have been a marketing device intended to divert the authorities, since the poison was openly sold both as a cosmetic and a devotionary object in vials that included a picture of St. Nicholas. Some of her customers claimed to have used it for its advertised purposes and only caused deaths accidentally. Over 600 victims are alleged to have died from this poison, mostly abusive husbands, in a time where woman did not have any rights or protection. Tofana was arrested and confessed to producing the poison, and she implicated a number of her clients, claiming that they knew what they were buying. She was executed in July 1659. There was much disquiet throughout Italy and many of her clients fled, while others were strangled in prison, and indeed many were publicly executed. Between 1666 and 1676 the Marchioness de Brinvilliers poisoned her father, two brothers, amongst others, and was executed on July 16, 1676.[2]

Ingredients

The ingredients of the mixture are basically known but not how they were blended. Aqua Tofana contained mostly arsenic and lead and possibly belladonna. It was a colorless, tasteless liquid and therefore easily mixed with water or wine to be served during meals.

Symptoms

Poisoning by Aqua Tofana could go unnoticed as the substance is clear and has no taste. It is slow acting, resembling death from progressed diseases other natural causes. The symptoms seen are similar to the effects of arsenic poisoning. There were a number of symptoms exhibited by those poisoned by Aqua Tofana. The first small dosage would produce cold-like symptoms. The victim was very ill by the third dosage; symptoms include vomiting, dehydration, diarrhoea and a burning sensation in the digestive system. The antidote often given was vinegar and lemon juice. The fourth dosage would kill the victim. As it was slow acting it allowed victims time to prepare for their death, including writing a will and repenting.[3][4]

Legend about Mozart

The legend that Mozart (1756—1791) might have been poisoned using Aqua Tofana[5] is completely unsubstantiated, even though it was Mozart himself who started this rumor.[6] Research by musicologists Oliver Hahn and Claudia Maurer Zenck on Mozart's manuscripts, however, found large amounts of arsenic in the manuscript of Die Zauberflöte, the opera Mozart was working on towards the end of his life. Arsenic is one of the most important ingredients of Aqua Tofana.

A source of confusion

Tofana is in many sources confused with Hieronyma Spara, "La Spara", a woman with a similar profession in Italy about the same time. Probably this is another name for the 'astrologa della Lungara'.

References

- Academia.edu: Aqua Tofana | Mike Dash - Academia.edu, accessdate: February 24, 2017

- Dictionary of Dates by Benjamin Vincent, London 1863.

- Dash, Mike (2017). "Chapter 6 - Aqua Tofana". In Wexler, Philip (ed.). Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Academic Press. pp. 63–69. ISBN 9780128095546.

- "Aqua Tofana: slow-poisoning and husband-killing in 17th century Italy". A Blast From The Past. 6 April 2015.

- Chorley, Henry Fothergill. 1854. Modern German Music: Recollections and Criticisms. London: Smith, Elder & Co., p. 193.

- Robbins Landon, H. C., 1791: Mozart's Last Year, Schirmer Books, New York (1988), pp. 148 ff.