Antimatroid

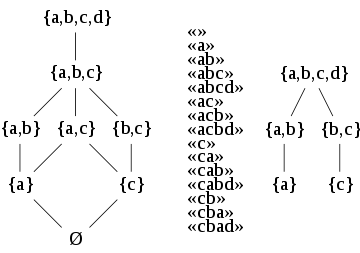

In mathematics, an antimatroid is a formal system that describes processes in which a set is built up by including elements one at a time, and in which an element, once available for inclusion, remains available until it is included. Antimatroids are commonly axiomatized in two equivalent ways, either as a set system modeling the possible states of such a process, or as a formal language modeling the different sequences in which elements may be included. Dilworth (1940) was the first to study antimatroids, using yet another axiomatization based on lattice theory, and they have been frequently rediscovered in other contexts;[1] see Korte et al. (1991) for a comprehensive survey of antimatroid theory with many additional references.

The axioms defining antimatroids as set systems are very similar to those of matroids, but whereas matroids are defined by an exchange axiom (e.g., the basis exchange, or independent set exchange axioms), antimatroids are defined instead by an anti-exchange axiom, from which their name derives. Antimatroids can be viewed as a special case of greedoids and of semimodular lattices, and as a generalization of partial orders and of distributive lattices. Antimatroids are equivalent, by complementation, to convex geometries, a combinatorial abstraction of convex sets in geometry.

Antimatroids have been applied to model precedence constraints in scheduling problems, potential event sequences in simulations, task planning in artificial intelligence, and the states of knowledge of human learners.

Definitions

An antimatroid can be defined as a finite family F of sets, called feasible sets, with the following two properties:

- The union of any two feasible sets is also feasible. That is, F is closed under unions.

- If S is a nonempty feasible set, then there exists some x in S such that S \ {x} (the set formed by removing x from S) is also feasible. That is, F is an accessible set system.

Antimatroids also have an equivalent definition as a formal language, that is, as a set of strings defined from a finite alphabet of symbols. A language L defining an antimatroid must satisfy the following properties:

- Every symbol of the alphabet occurs in at least one word of L.

- Each word of L contains at most one copy of any symbol.

- Every prefix of a string in L is also in L.

- If s and t are strings in L, and s contains at least one symbol that is not in t, then there is a symbol x in s such that tx is another string in L.

If L is an antimatroid defined as a formal language, then the sets of symbols in strings of L form an accessible union-closed set system. In the other direction, if F is an accessible union-closed set system, and L is the language of strings s with the property that the set of symbols in each prefix of s is feasible, then L defines an antimatroid. Thus, these two definitions lead to mathematically equivalent classes of objects.[2]

Examples

- A chain antimatroid has as its formal language the prefixes of a single word, and as its feasible sets the sets of symbols in these prefixes. For instance the chain antimatroid defined by the word "abcd" has as its formal language the strings {ε, "a", "ab", "abc", "abcd"} and as its feasible sets the sets Ø, {a}, {a,b}, {a,b,c}, and {a,b,c,d}.[3]

- A poset antimatroid has as its feasible sets the lower sets of a finite partially ordered set. By Birkhoff's representation theorem for distributive lattices, the feasible sets in a poset antimatroid (ordered by set inclusion) form a distributive lattice, and any distributive lattice can be formed in this way. Thus, antimatroids can be seen as generalizations of distributive lattices. A chain antimatroid is the special case of a poset antimatroid for a total order.[3]

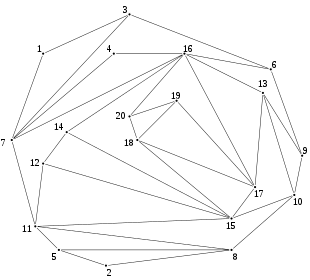

- A shelling sequence of a finite set U of points in the Euclidean plane or a higher-dimensional Euclidean space is an ordering on the points such that, for each point p, there is a line (in the Euclidean plane, or a hyperplane in a Euclidean space) that separates p from all later points in the sequence. Equivalently, p must be a vertex of the convex hull of it and all later points. The partial shelling sequences of a point set form an antimatroid, called a shelling antimatroid. The feasible sets of the shelling antimatroid are the intersections of U with the complement of a convex set.[3] Every antimatroid is isomorphic to a shelling antimatroid of points in a sufficiently high-dimensional space.[4]

- A perfect elimination ordering of a chordal graph is an ordering of its vertices such that, for each vertex v, the neighbors of v that occur later than v in the ordering form a clique. The prefixes of perfect elimination orderings of a chordal graph form an antimatroid.[3] Antimatroids also describe some other kinds of vertex removal orderings in graphs, such as the dismantling orders of cop-win graphs.

Paths and basic words

In the set theoretic axiomatization of an antimatroid there are certain special sets called paths that determine the whole antimatroid, in the sense that the sets of the antimatroid are exactly the unions of paths. If S is any feasible set of the antimatroid, an element x that can be removed from S to form another feasible set is called an endpoint of S, and a feasible set that has only one endpoint is called a path of the antimatroid. The family of paths can be partially ordered by set inclusion, forming the path poset of the antimatroid.

For every feasible set S in the antimatroid, and every element x of S, one may find a path subset of S for which x is an endpoint: to do so, remove one at a time elements other than x until no such removal leaves a feasible subset. Therefore, each feasible set in an antimatroid is the union of its path subsets. If S is not a path, each subset in this union is a proper subset of S. But, if S is itself a path with endpoint x, each proper subset of S that belongs to the antimatroid excludes x. Therefore, the paths of an antimatroid are exactly the sets that do not equal the unions of their proper subsets in the antimatroid. Equivalently, a given family of sets P forms the set of paths of an antimatroid if and only if, for each S in P, the union of subsets of S in P has one fewer element than S itself. If so, F itself is the family of unions of subsets of P.

In the formal language formalization of an antimatroid we may also identify a subset of words that determine the whole language, the basic words. The longest strings in L are called basic words; each basic word forms a permutation of the whole alphabet. For instance, the basic words of a poset antimatroid are the linear extensions of the given partial order. If B is the set of basic words, L can be defined from B as the set of prefixes of words in B. It is often convenient to define antimatroids from basic words in this way, but it is not straightforward to write an axiomatic definition of antimatroids in terms of their basic words.

Convex geometries

If F is the set system defining an antimatroid, with U equal to the union of the sets in F, then the family of sets

complementary to the sets in F is sometimes called a convex geometry and the sets in G are called convex sets. For instance, in a shelling antimatroid, the convex sets are intersections of U with convex subsets of the Euclidean space into which U is embedded.

Complementarily to the properties of set systems that define antimatroids, the set system defining a convex geometry should be closed under intersections, and for any set S in G that is not equal to U there must be an element x not in S that can be added to S to form another set in G.

A convex geometry can also be defined in terms of a closure operator τ that maps any subset of U to its minimal closed superset. To be a closure operator, τ should have the following properties:

- τ(∅) = ∅: the closure of the empty set is empty.

- Any set S is a subset of τ(S).

- If S is a subset of T, then τ(S) must be a subset of τ(T).

- For any set S, τ(S) = τ(τ(S)).

The family of closed sets resulting from a closure operation of this type is necessarily closed under intersections. The closure operators that define convex geometries also satisfy an additional anti-exchange axiom:

- If neither y nor z belong to τ(S), but z belongs to τ(S ∪ {y}), then y does not belong to τ(S ∪ {z}).

A closure operation satisfying this axiom is called an anti-exchange closure. If S is a closed set in an anti-exchange closure, then the anti-exchange axiom determines a partial order on the elements not belonging to S, where x ≤ y in the partial order when x belongs to τ(S ∪ {y}). If x is a minimal element of this partial order, then S ∪ {x} is closed. That is, the family of closed sets of an anti-exchange closure has the property that for any set other than the universal set there is an element x that can be added to it to produce another closed set. This property is complementary to the accessibility property of antimatroids, and the fact that intersections of closed sets are closed is complementary to the property that unions of feasible sets in an antimatroid are feasible. Therefore, the complements of the closed sets of any anti-exchange closure form an antimatroid.[5]

The undirected graphs in which the convex sets (subsets of vertices that contain all shortest paths between vertices in the subset) form a convex geometry are exactly the Ptolemaic graphs.[6]

Join-distributive lattices

Any two sets in an antimatroid have a unique least upper bound (their union) and a unique greatest lower bound (the union of the sets in the antimatroid that are contained in both of them). Therefore, the sets of an antimatroid, partially ordered by set inclusion, form a lattice. Various important features of an antimatroid can be interpreted in lattice-theoretic terms; for instance the paths of an antimatroid are the join-irreducible elements of the corresponding lattice, and the basic words of the antimatroid correspond to maximal chains in the lattice. The lattices that arise from antimatroids in this way generalize the finite distributive lattices, and can be characterized in several different ways.

- The description originally considered by Dilworth (1940) concerns meet-irreducible elements of the lattice. For each element x of an antimatroid, there exists a unique maximal feasible set Sx that does not contain x (Sx is the union of all feasible sets not containing x). Sx is meet-irreducible, meaning that it is not the meet of any two larger lattice elements: any larger feasible set, and any intersection of larger feasible sets, contains x and so does not equal Sx. Any element of any lattice can be decomposed as a meet of meet-irreducible sets, often in multiple ways, but in the lattice corresponding to an antimatroid each element T has a unique minimal family of meet-irreducible sets Sx whose meet is T; this family consists of the sets Sx such that T ∪ {x} belongs to the antimatroid. That is, the lattice has unique meet-irreducible decompositions.

- A second characterization concerns the intervals in the lattice, the sublattices defined by a pair of lattice elements x ≤ y and consisting of all lattice elements z with x ≤ z ≤ y. An interval is atomistic if every element in it is the join of atoms (the minimal elements above the bottom element x), and it is Boolean if it is isomorphic to the lattice of all subsets of a finite set. For an antimatroid, every interval that is atomistic is also boolean.

- Thirdly, the lattices arising from antimatroids are semimodular lattices, lattices that satisfy the upper semimodular law that for any two elements x and y, if y covers x ∧ y then x ∨ y covers x. Translating this condition into the sets of an antimatroid, if a set Y has only one element not belonging to X then that one element may be added to X to form another set in the antimatroid. Additionally, the lattice of an antimatroid has the meet-semidistributive property: for all lattice elements x, y, and z, if x ∧ y and x ∧ z are both equal then they also equal x ∧ (y ∨ z). A semimodular and meet-semidistributive lattice is called a join-distributive lattice.

These three characterizations are equivalent: any lattice with unique meet-irreducible decompositions has boolean atomistic intervals and is join-distributive, any lattice with boolean atomistic intervals has unique meet-irreducible decompositions and is join-distributive, and any join-distributive lattice has unique meet-irreducible decompositions and boolean atomistic intervals.[7] Thus, we may refer to a lattice with any of these three properties as join-distributive. Any antimatroid gives rise to a finite join-distributive lattice, and any finite join-distributive lattice comes from an antimatroid in this way.[8] Another equivalent characterization of finite join-distributive lattices is that they are graded (any two maximal chains have the same length), and the length of a maximal chain equals the number of meet-irreducible elements of the lattice.[9] The antimatroid representing a finite join-distributive lattice can be recovered from the lattice: the elements of the antimatroid can be taken to be the meet-irreducible elements of the lattice, and the feasible set corresponding to any element x of the lattice consists of the set of meet-irreducible elements y such that y is not greater than or equal to x in the lattice.

This representation of any finite join-distributive lattice as an accessible family of sets closed under unions (that is, as an antimatroid) may be viewed as an analogue of Birkhoff's representation theorem under which any finite distributive lattice has a representation as a family of sets closed under unions and intersections.

Supersolvable antimatroids

Motivated by a problem of defining partial orders on the elements of a Coxeter group, Armstrong (2007) studied antimatroids which are also supersolvable lattices. A supersolvable antimatroid is defined by a totally ordered collection of elements, and a family of sets of these elements. The family must include the empty set. Additionally, it must have the property that if two sets A and B belong to the family, the set-theoretic difference B \ A is nonempty, and x is the smallest element of B \ A, then A ∪ {x} also belongs to the family. As Armstrong observes, any family of sets of this type forms an antimatroid. Armstrong also provides a lattice-theoretic characterization of the antimatroids that this construction can form.

Join operation and convex dimension

If A and B are two antimatroids, both described as a family of sets, and if the maximal sets in A and B are equal, we can form another antimatroid, the join of A and B, as follows:

This is a different operation than the join considered in the lattice-theoretic characterizations of antimatroids: it combines two antimatroids to form another antimatroid, rather than combining two sets in an antimatroid to form another set. The family of all antimatroids that have a given maximal set forms a semilattice with this join operation.

Joins are closely related to a closure operation that maps formal languages to antimatroids, where the closure of a language L is the intersection of all antimatroids containing L as a sublanguage. This closure has as its feasible sets the unions of prefixes of strings in L. In terms of this closure operation, the join is the closure of the union of the languages of A and B.

Every antimatroid can be represented as a join of a family of chain antimatroids, or equivalently as the closure of a set of basic words; the convex dimension of an antimatroid A is the minimum number of chain antimatroids (or equivalently the minimum number of basic words) in such a representation. If F is a family of chain antimatroids whose basic words all belong to A, then F generates A if and only if the feasible sets of F include all paths of A. The paths of A belonging to a single chain antimatroid must form a chain in the path poset of A, so the convex dimension of an antimatroid equals the minimum number of chains needed to cover the path poset, which by Dilworth's theorem equals the width of the path poset.[10]

If one has a representation of an antimatroid as the closure of a set of d basic words, then this representation can be used to map the feasible sets of the antimatroid into d-dimensional Euclidean space: assign one coordinate per basic word w, and make the coordinate value of a feasible set S be the length of the longest prefix of w that is a subset of S. With this embedding, S is a subset of T if and only if the coordinates for S are all less than or equal to the corresponding coordinates of T. Therefore, the order dimension of the inclusion ordering of the feasible sets is at most equal to the convex dimension of the antimatroid.[11] However, in general these two dimensions may be very different: there exist antimatroids with order dimension three but with arbitrarily large convex dimension.

Enumeration

The number of possible antimatroids on a set of elements grows rapidly with the number of elements in the set. For sets of one, two, three, etc. elements, the number of distinct antimatroids is

Applications

Both the precedence and release time constraints in the standard notation for theoretic scheduling problems may be modeled by antimatroids. Boyd & Faigle (1990) use antimatroids to generalize a greedy algorithm of Eugene Lawler for optimally solving single-processor scheduling problems with precedence constraints in which the goal is to minimize the maximum penalty incurred by the late scheduling of a task.

Glasserman & Yao (1994) use antimatroids to model the ordering of events in discrete event simulation systems.

Parmar (2003) uses antimatroids to model progress towards a goal in artificial intelligence planning problems.

In Optimality Theory, grammars are logically equivalent to antimatroids (Merchant & Riggle (2016)).

In mathematical psychology, antimatroids have been used to describe feasible states of knowledge of a human learner. Each element of the antimatroid represents a concept that is to be understood by the learner, or a class of problems that he or she might be able to solve correctly, and the sets of elements that form the antimatroid represent possible sets of concepts that could be understood by a single person. The axioms defining an antimatroid may be phrased informally as stating that learning one concept can never prevent the learner from learning another concept, and that any feasible state of knowledge can be reached by learning a single concept at a time. The task of a knowledge assessment system is to infer the set of concepts known by a given learner by analyzing his or her responses to a small and well-chosen set of problems. In this context antimatroids have also been called "learning spaces" and "well-graded knowledge spaces".[12]

Notes

- Two early references are Edelman (1980) and Jamison (1980); Jamison was the first to use the term "antimatroid". Monjardet (1985) surveys the history of rediscovery of antimatroids.

- Korte et al., Theorem 1.4.

- Gordon (1997) describes several results related to antimatroids of this type, but these antimatroids were mentioned earlier e.g. by Korte et al. Chandran et al. (2003) use the connection to antimatroids as part of an algorithm for efficiently listing all perfect elimination orderings of a given chordal graph.

- Kashiwabara, Nakamura & Okamoto (2005).

- Korte et al., Theorem 1.1.

- Farber & Jamison (1986).

- Adaricheva, Gorbunov & Tumanov (2003), Theorems 1.7 and 1.9; Armstrong (2007), Theorem 2.7.

- Edelman (1980), Theorem 3.3; Armstrong (2007), Theorem 2.8.

- Monjardet (1985) credits a dual form of this characterization to several papers from the 1960s by S. P. Avann.

- Edelman & Saks (1988); Korte et al., Theorem 6.9.

- Korte et al., Corollary 6.10.

- Doignon & Falmagne (1999).

References

- Adaricheva, K. V.; Gorbunov, V. A.; Tumanov, V. I. (2003), "Join-semidistributive lattices and convex geometries", Advances in Mathematics, 173 (1): 1–49, doi:10.1016/S0001-8708(02)00011-7.

- Armstrong, Drew (2007), The sorting order on a Coxeter group, arXiv:0712.1047, Bibcode:2007arXiv0712.1047A.

- Birkhoff, Garrett; Bennett, M. K. (1985), "The convexity lattice of a poset", Order, 2 (3): 223–242, doi:10.1007/BF00333128 (inactive 2020-04-29).

- Björner, Anders; Ziegler, Günter M. (1992), "Introduction to greedoids", in White, Neil (ed.), Matroid Applications, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, 40, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 284–357, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511662041.009, ISBN 0-521-38165-7, MR 1165537CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boyd, E. Andrew; Faigle, Ulrich (1990), "An algorithmic characterization of antimatroids", Discrete Applied Mathematics, 28 (3): 197–205, doi:10.1016/0166-218X(90)90002-T.

- Chandran, L. S.; Ibarra, L.; Ruskey, F.; Sawada, J. (2003), "Generating and characterizing the perfect elimination orderings of a chordal graph" (PDF), Theoretical Computer Science, 307 (2): 303–317, doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(03)00221-4

- Dilworth, Robert P. (1940), "Lattices with unique irreducible decompositions", Annals of Mathematics, 41 (4): 771–777, doi:10.2307/1968857, JSTOR 1968857.

- Doignon, Jean-Paul; Falmagne, Jean-Claude (1999), Knowledge Spaces, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-64501-2.

- Edelman, Paul H. (1980), "Meet-distributive lattices and the anti-exchange closure", Algebra Universalis, 10 (1): 290–299, doi:10.1007/BF02482912.

- Edelman, Paul H.; Saks, Michael E. (1988), "Combinatorial representation and convex dimension of convex geometries", Order, 5 (1): 23–32, doi:10.1007/BF00143895.

- Farber, Martin; Jamison, Robert E. (1986), "Convexity in graphs and hypergraphs", SIAM Journal on Algebraic and Discrete Methods, 7 (3): 433–444, doi:10.1137/0607049, hdl:10338.dmlcz/127659, MR 0844046.

- Glasserman, Paul; Yao, David D. (1994), Monotone Structure in Discrete Event Systems, Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics, Wiley Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-58041-6.

- Gordon, Gary (1997), "A β invariant for greedoids and antimatroids", Electronic Journal of Combinatorics, 4 (1): Research Paper 13, doi:10.37236/1298, MR 1445628.

- Jamison, Robert (1980), "Copoints in antimatroids", Proceedings of the Eleventh Southeastern Conference on Combinatorics, Graph Theory and Computing (Florida Atlantic Univ., Boca Raton, Fla., 1980), Vol. II, Congressus Numerantium, 29, pp. 535–544, MR 0608454.

- Kashiwabara, Kenji; Nakamura, Masataka; Okamoto, Yoshio (2005), "The affine representation theorem for abstract convex geometries", Computational Geometry, 30 (2): 129–144, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.14.4965, doi:10.1016/j.comgeo.2004.05.001, MR 2107032.

- Korte, Bernhard; Lovász, László; Schrader, Rainer (1991), Greedoids, Springer-Verlag, pp. 19–43, ISBN 3-540-18190-3.

- Merchant, Nazarre; Riggle, Jason (2016), "OT grammars, beyond partial orders: ERC sets and antimatroids", Nat Lang Linguist Theory, 34: 241–269, doi:10.1007/s11049-015-9297-5.

- Monjardet, Bernard (1985), "A use for frequently rediscovering a concept", Order, 1 (4): 415–417, doi:10.1007/BF00582748.

- Parmar, Aarati (2003), "Some Mathematical Structures Underlying Efficient Planning", AAAI Spring Symposium on Logical Formalization of Commonsense Reasoning (PDF).