Anonymus Londinensis

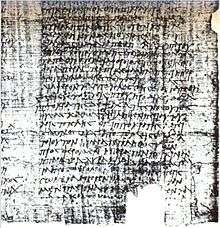

Anonymus Londinensis (or Anonymus Londiniensis) is the name given to an anonymous Ancient Greek author of approximately the 1st century AD whose work On Medicine (Ancient Greek: Ἰατρικά, Latin: De Medicina) is partially preserved in a papyrus in the British Library (PBrLibr inv. 137 = P.Lit.Lond. 165). It ranks as the most important surviving medical papyrus and provides important information about the history of Greek medical thought.

On Medicine

While only fragments survive of some portions of the text, the papyrus containing the work of Anonymus Londinensis is exceptionally well preserved, with 3.5 meters of the roll largely intact, containing almost 2,000 lines of text in 39 columns. It seems to be an unfinished draft (breaking off in mid-column) in the hand of the author, who compiled, digested, and manipulated various sources as he wrote, so that we may even observe the process of his thinking as he writes.[1]

The text consists of three parts: a series of definitions related to the affections of the body and soul (cols. 1-4), a doxographical part (cols. 4-20), and a physiological part (cols. 21-39).

Menoneia

The doxographical part is a survey of 5th and 4th century writers on the causes of disease, following a source called "Aristotle" but usually ascribed to Aristotle's pupil Meno and identified with the title Menoneia mentioned in Plutarch's Quaestiones convivales VIII.ix, 377c. This work would have been part of the early Peripatetic project to survey all of the most important fields of knowledge. The views of some twenty physicians are reported, with Plato cited more than any other authority, even Hippocrates. The authorities are classified into two groups, one holding that disease is caused by residues of food, the other by disturbances in the balance of the bodily elements.

Hermann Diels had suggested that Anonymus Londinensis knew this Peripatetic doxography through the Areskonta of Alexander Philalethes, but there is little plausible justification for this view.[2]

On physiology

The final, incomplete, section of the work discusses physiology in a manner influenced by dialectical argument. Only the views of Aristotle and subsequent authors are considered, including Herophilus (who appears in a comparatively positive light), Erasistratus (who is attacked together with his followers), Asclepiades of Bithynia, and Alexander Philalethes. This interesting section contains ideas about vitality and motion, nutriment, the various emanations from the body, digestion, veins and arteries, and the invisible "pores."[3]

Editions and translations

The papyrus was first described by Frederic G. Kenyon in 1892. Diels produced the first edition of the Greek text, which was published in 1893 by the Prussian Academy of Sciences as volume III, part 1, of Supplementum Aristotelicum. A German translation of Diels' text by Heinrich Beckh and Franz Spät was published in 1896 (Anonymus Londinensis: Auszüge eines Unbekannten aus Aristoteles-Menons Handbuch der Medicin und aus Werken anderer älterer Aerzte). W.H.S. Jones reprinted Diels' Greek text together with his own English translation and commentary in The Medical Writings of Anonymus Londinensis, Cambridge University Press, 1947 (repr. Amsterdam 1968; repr. Cambridge 2011, ISBN 0-521-17069-9). A new Teubner edition of the Greek text by Daniela Manetti was published in 2011 (ISBN 3110218712), while Antonio Ricciardetto published a critical text in 2013 and reprised it as a Greek-French bilingual text in the Collection Budé series in 2016. An edition by Jackie Pigeaud has also been announced.

Notes

- D. Manetti, "'Aristotle' and the role of doxography in the Anonymus Londiniensis (PBrLibr Inv. 137)," in van der Eijk 1999, p. 97

- Heinrich von Staden, "Rupture and continuity: Hellenistic reflections on the history of medicine," in van der Eijk 1999, p. 164

- W.J.Bishop "Anonymus Londinensis" (review of Jones 1947), British Medical Bulletin 5 (1947-8), p. 387

Further reading

- Markus Asper, Griechische Wissenschaftstexte: Formen, Funktionen, Differenzierungsgeschichten, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2007, pp. 293-304

- Philip J. van der Eijk (ed.), Ancient histories of medicine: essays in medical doxography and historiography in classical antiquity, Leiden: Brill, 1999

External links

- Greek text (Diels 1893): BBAW online edition; via Google Books, c.1, c.2, c.3, c.4

- French translation