Animal welfare in Nazi Germany

There was widespread support for animal welfare in Nazi Germany[1] among the country's leadership. Adolf Hitler and his top officials took a variety of measures to ensure animals were protected.[2] Many Nazi leaders, including Hitler and Hermann Göring, were supporters of animal rights and conservation.

Several Nazis were environmentalists, and species protection and animal welfare were significant issues in the Nazi regime.[3] Heinrich Himmler made an effort to ban the hunting of animals.[4] Göring was a professed animal lover and conservationist,[5] who, on instructions from Hitler, committed Germans who violated Nazi animal welfare laws to concentration camps. In his private diaries, Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels described Hitler as a vegetarian whose hatred of the Jewish and Christian religions in large part stemmed from the ethical distinction these faiths drew between the value of humans and the value of other animals; Goebbels also mentions that Hitler planned to ban slaughterhouses in the German Reich following the conclusion of World War II.[6]

The current animal welfare laws in Germany are diluted versions of the laws introduced by the Nazis.[7]

Measures

At the end of the nineteenth century, kosher butchering and vivisection (animal experimentation) were the main concerns of the German animal welfare movement. The Nazis adopted these concerns as part of their political platform.[8] According to Boria Sax, the Nazis rejected anthropocentric reasons for animal protection—animals were to be protected for their own sake.[9] In 1927, a Nazi representative to the Reichstag called for actions against cruelty to animals and kosher butchering.[8]

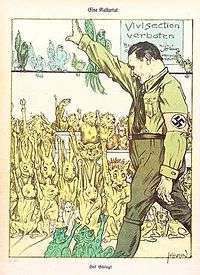

In 1931, the Nazi Party (then a minority in the Reichstag) proposed a ban on vivisection, but the ban failed to attract support from other political parties. By 1933, after Hitler had ascended to the Chancellery and the Nazis had consolidated control of the Reichstag, the Nazis immediately held a meeting to enact the ban on vivisection. On April 21, 1933, almost immediately after the Nazis came to power, the parliament began to pass laws for the regulation of animal slaughter.[8] On April 21, a law was passed concerning the slaughter of animals; no animals were to be slaughtered without anesthetic.

On April 24, Order of the Prussian Ministry of the Interior was enacted regarding the slaughter of poikilotherms.[10] Germany was the first nation to ban vivisection.[11] A law imposing total ban on vivisection was enacted on August 16, 1933, by Hermann Göring as the prime minister of Prussia.[12] He announced an end to the "unbearable torture and suffering in animal experiments" and said that those who "still think they can continue to treat animals as inanimate property" will be sent to concentration camps.[8] On August 28, 1933, Göring announced in a radio broadcast:[13]

An absolute and permanent ban on vivisection is not only a necessary law to protect animals and to show sympathy with their pain, but it is also a law for humanity itself.... I have therefore announced the immediate prohibition of vivisection and have made the practice a punishable offense in Prussia. Until such time as punishment is pronounced the culprit shall be lodged in a concentration camp.[13]

Göring also banned commercial animal trapping and imposed severe restrictions on hunting. He prohibited boiling of lobsters and crabs. In one incident, he sent a fisherman to a concentration camp[13] for cutting up a bait frog.[11]

On November 24, 1933, Nazi Germany enacted another law called Reichstierschutzgesetz (Reich Animal Protection Act), for protection of animals.[14][15] This law listed many prohibitions against the use of animals, including their use for filmmaking and other public events causing pain or damage to health,[16] feeding fowls forcefully and tearing out the thighs of living frogs.[17] The two principals (Ministerialräte) of the German Ministry of the Interior, Clemens Giese and Waldemar Kahler, who were responsible for drafting the legislative text,[15] wrote in their juridical comment from 1939, that by the law the animal was to be "protected for itself" ("um seiner selbst willen geschützt"), and made "an object of protection going far beyond the hitherto existing law" ("Objekt eines weit über die bisherigen Bestimmungen hinausgehenden Schutzes").[18]

On February 23, 1934, a decree was enacted by the Prussian Ministry of Commerce and Employment which introduced education on animal protection laws at primary, secondary and college levels.[10] On 3 July 1934, a law Das Reichsjagdgesetz (The Reich Hunting Law) was enacted which limited hunting. The act also created the German Hunting Society with a mission to educate the hunting community in ethical hunting. July 1, 1935, another law Reichsnaturschutzgesetz (Reich Nature Conservation Act) was passed to protect nature.[15] According to an article published in Kaltio, one of the main Finnish cultural magazines, Nazi Germany was the first state in the world to place the wolf under protection.[19] Nazi Germany "introduced the first legislation for the protection of wolves."[20]

In 1934, Nazi Germany hosted an international conference on animal welfare in Berlin.[21] On March 27, 1936, an order on the slaughter of living fish and other poikilotherms was enacted. On March 18 the same year, an order was passed on afforestation and on protection of animals in the wild.[10] On September 9, 1937, a decree was published by the Ministry of the Interior which specified guidelines for the transportation of animals.[22] In 1938, the Nazis introduced animal protection as a subject to be taught in public schools and universities in Germany.[21]

Effectiveness

Although various laws were enacted for animal protection, the extent to which they were enforced has been questioned. The law enacted by Hermann Göring on August 16, 1933, banning vivisection was revised by a decree of September 5 of that year, with more lax provisions, then allowing the Reich Interior Ministry to distribute permits to some universities and research institutes to conduct animal experiments under conditions of anesthesia and scientific need.[23] According to Pfugers Archiv für die Gesamte Physiologie (Pfugers Archive for the Total Physiology), a science journal at that time, there were many animal experiments during the Nazi regime.[24] In 1936, the Tierärztekammer (Chamber of Veterinarians) in Darmstadt filed a formal complaint against the lack of enforcement of the animal protection laws on those who conducted illegal animal testing.[25]

Controversies

Policies regarding non-Nazi activists

Animal rights activist Boria Sax argues in his book Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust that the Nazis manipulated attitudes towards animal protection to conform to their own symbolic system. Presumably, by equating the National Socialist German Workers Party with "nature", the Nazis reduced ethical issues to biological questions.[26]

Scholars who argue that the Nazis were not authentic supporters of animal rights point out that the Nazi regime disbanded some organizations advocating environmentalism or animal protection. However these organizations, such as the 100,000-member strong Friends of Nature, were disbanded because they advocated political ideologies that were illegal under Nazi law.[27] For example, the Friends of Nature was officially nonpartisan, but activists from the major rival party, the Social Democratic Party, were prominent among its leaders.[28]

See also

Notes

- Thomas R. DeGregori (2002). Bountiful Harvest: Technology, Food Safety, and the Environment. Cato Institute. p. 153. ISBN 1-930865-31-7.

- Arnold Arluke; Clinton Sanders (1996). Regarding Animals. Temple University Press. p. 132. ISBN 1-56639-441-4.

- Robert Proctor (1999). The Nazi War on Cancer. Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-691-07051-2.

- Martin Kitchen (2006). A History of Modern Germany, 1800-2000. Blackwell Publishing. p. 278. ISBN 1-4051-0040-0.

- Seymour Rossel (1992). The Holocaust: The World and the Jews, 1933-1945. Behrman House, Inc. p. 79. ISBN 0-87441-526-8.

- Goebbels, Joseph; Louis P. Lochner (trans.) (1993). The Goebbels Diaries. Charter Books. p. 679. ISBN 0-441-29550-9.

- Bruce Braun, Noel Castree (1998). Remaking Reality: Nature at the Millenium. Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 0-415-14493-0.

- Arnold Arluke, Clinton Sanders (1996). Regarding Animals. Temple University Press. p. 133. ISBN 1-56639-441-4.

- Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 42. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 181. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- Kathleen Marquardt (1993). Animalscam: The Beastly Abuse of Human Rights. Regnery Publishing. p. 125. ISBN 0-89526-498-6.

- Frank Uekötter (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-521-84819-9.

- Kathleen Marquardt (1993). Animalscam: The Beastly Abuse of Human Rights. Regnery Publishing. p. 124. ISBN 0-89526-498-6.

- Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 179. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- Luc Ferry (1995). The New Ecological Order. University of Chicago Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-226-24483-0.

- Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 175. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 176. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- Clemens Giese and Waldemar Kahler (1939). Das deutsche Tierschutzrecht, Bestimmungen zum Schutz der Tiere, Berlin, cited from: Edeltraud Klüting. Die gesetzlichen Regelungen der nationalsozialistischen Reichsregierung für den Tierschutz, den Naturschutz und den Umweltschutz, in: Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter (ed., 2003). Naturschutz und Nationalsozialismus, Campus Verlag ISBN 3-593-37354-8, p.77 (in German)

- Aikio, Aslak (February 2003). "Animal Rights in the Third Reich". Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Sax, Boria (2001). The Mythical Zoo: an Encyclopedia of Animals in World Myth, Legend, and Literature. ABC-CLIO. p. 272. ISBN 1-5760-7612-1.

- Arnold Arluke, Clinton Sanders (1996). Regarding Animals. Temple University Press. p. 137. ISBN 1-56639-441-4.

- Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 182. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- Frank Uekötter (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 0-521-84819-9.

- C. Ray Greek, Jean Swingle Greek (2002). Sacred Cows and Golden Geese: The Human Cost of Experiments on Animals. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 90. ISBN 0-8264-1402-8.

- Frank Uekötter (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-521-84819-9.

- Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 41. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- William T Markham (2008). Environmental Organisations in Modern Germany: Hardy Survivors in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Regnery Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0857450302.