Andries de Graeff

Free Imperial Knight Andries de Graeff (19 February 1611 – 30 November 1678) was a very powerful member of the Amsterdam branch of the De Graeff - family during the Dutch Golden Age. He became a mayor of Amsterdam and a powerful Amsterdam regent after the death of his older brother Cornelis de Graeff. Like him and their father Jacob Dircksz de Graeff he opposed the house of Orange. In the mid-17th century he controlled the finances and politics.[1]

Andries de Graeff | |

|---|---|

| Andries de Graeff (1661) by Artus Quellinus | |

| Finance minister of Holland | |

| In office 1652–1657 | |

| Preceded by | Adriaan Pauw |

| Succeeded by | Jacob de Witt |

| Regent and Mayor of Amsterdam | |

| In office 1657–1672 | |

| Preceded by | Cornelis de Graeff |

| Succeeded by | Gillis Valckenier and Coenraad van Beuningen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 February 1611 Amsterdam |

| Died | 30 November 1678 Amsterdam |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Political party | States Faction |

| Spouse(s) | Elisabeth Bicker van Swieten |

| Relations | Cornelis de Graeff (brother) Andries Bicker (cousin) Jan de Witt (nephew) Cornelis de Witt (nephew) Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft (uncle) |

| Children | Cornelis, Alia and Arnoldina (Aertje) |

| Residence | Herengracht 446, Amsterdam, country houses Vredehof near Voorschoten and Graeffenveld near Oud-Naarden |

| Occupation | Regent / Mayor and Landlord |

Andries de Graeff followed in his father's and brother's footsteps and, between 1657 and 1672, was appointed mayor some seven times. De Graeff was a member of a family of regents who belonged to the republican political movement also referred to as the ‘state oriented’, as opposed to the Royalists. Andries was called the last regent and mayor from the dynastie of the "Graven", who was powerful and able enough to ruled the city of Amsterdam.[2]

De Graeff was a Free Imperial Knight of the Holy Roman Empire,[3] an Ambachtsheer (Lord of the manor) from Urk en Emmeloord, during the late 1650s chiefcouncillor of the Admiralty of Amsterdam,[4] chieflandholder of the Watergraafsmeer and dijkgraaf van Nieuwer-Amstel.[5]

Together with his brother Cornelis De Graeff he became an illustrious Patron and Art collector.[5]

Family De Graeff

Andries de Graeff was born in Amsterdam, the third son of Jacob Dircksz de Graeff and Aaltje Boelens Loen. His older sister Agneta who married Jan Bicker, was the mother of Johan de Witts wife Wendela Bicker. After he has been finished his study in Poitiers he was married to his niece Elisabeth Bicker van Swieten, daughter of the Amsterdam Mayor Cornelis Bicker van Swieten.[4]

Both his brother Cornelis and Andries were very critical of the Orange family’s influence. Together with the Republican political leader Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt, the De Graeff brothers strived for the abolition of stadtholdership. They desired the full sovereignty of the individual regions in a form in which the Republic of the United Seven Netherlands was not ruled by a single person. Instead of a sovereign (or stadtholder) the political and military power was lodged with the States General and with the regents of the cities in Holland.[2]

During the two decades the De Graeff family had a leading role in the Amsterdam administration, the city was at the peak of its political power. This period was also referred to by Republicans as the ‘Ware Vrijheid’ (True Freedom). It was the First Stadtholderless Period which lasted from 1650 to 1672. During these twenty years, the regents from Holland and in particular those of Amsterdam, controlled the republic. The city was flush with self-confidence and liked to compare itself to the famous Republic of Rome. Even without a stadtholder, things seemed to be going well for the Republic and its regents both politically and economically.[2]

Political career

Andries de Graeff was from 1646 a member of the vroedschap and from 1657-71 mayor seven times in the difficult times of the First Stadtholderless Period.[2][4] Between 1650 and 1657 he was advisor of finances and finance minister of Holland at Den Haag.

Like his brother Cornelis, their cousin Andries Bicker and Joan Huydecoper van Maarsseveen De Graeff became one of the main figures behind the building of a new city hall on the Dam, which was inaugurated in 1655.

In 1650 he started his career as advisor in the ministerium of finances in Den Haag. After he became a minister he went back to Amsterdam, and took place as a sort of chairing mayor of this city. After the death of his brother Cornelis, De Graeff became the strong leader of the republicans. He held this position until the rampjaar. He also became an advisor of the Admiralty of Amsterdam and in 1661 he was made an advisor of the States of Holland and West Friesland.[4]

The Dutch Gift

In 1660 the Dutch Gift was organized by the regents, especially Andries and his brother Cornelis.[5] The sculptures for the gift were selected by the pre-eminent sculptor in the Netherlands, Artus Quellinus, and Gerrit van Uylenburgh, the son of Rembrandt's dealer Hendrick van Uylenburgh, advised the States-General on the purchase. The Dutch Gift was a collection of 28 mostly Italian Renaissance paintings and 12 classical sculptures, along with a yacht, the Mary, and furniture, which was presented to King Charles II of England by the States-General of the Netherlands in 1660.[6]

Most of the paintings and all the Roman sculptures were from the Reynst collection, the most important seventeenth-century Dutch collection of paintings of the Italian sixteenth century, formed in Venice by Jan Reynst (1601–1646) and extended by his brother, Gerrit Reynst (1599–1658).

The collection was given to Charles II to mark his return to power in the English Restoration, before which Charles had spent many years in exile in the Dutch Republic during the rule of the English Commonwealth. It was intended to strengthen diplomatic relations between England and the Republic, but only a few years after the gift the two nations would be at war again in the Second Anglo-Dutch War of 1665–67.

Perpetual Edict (1667) and the Rampjaar 1672

.jpg)

In 1667 De Graeff was one of the "sponsors" (the other signers where De Witt, Gillis Valckenier and Gaspar Fagel) of the Perpetual Edict, that was a resolution of the States of Holland in which they abolished the office of Stadtholder in the province of Holland.[5] At approximately the same time a majority of provinces in the States-General of the Netherlands agreed to declare the office of stadtholder (in any of the provinces) incompatible with the office of Captain general of the Dutch Republic.

The Republic was in a dangerous position and war with France and England seemed imminent. The call for the return of a strong military leader from the Orange family was gaining momentum, particularly among commoners. A number of Amsterdam regents had started to realise that they needed to seek rapprochement with the Orangists. This put increasing pressure on Grand Pensionary Johan de Witts position. In 1670, the Amsterdamse Vroedschap (Amsterdam City Council) led by Mayors Valckenier and Coenraad van Beuningen decided to enter into an alliance with the Orangists and to offer the young prince William III of Orange a seat on the Council of State. This caused a definitive split between De Witt and the Orangist Amsterdam Group of regents around Mayor Valckenier. However, De Witt managed to push the turncoats into the Amsterdam city administration and they were sidelined during the vroedschap elections of February 1671.[2]

Andries de Graeff was once again put forward as mayor and managed to gain control with his Republican faction. During the winter of 1671 it seemed as if – at least in Amsterdam – the Republicans were winning. It was an exceptionally opportune moment to commission a monumental ceiling painting on Amsterdam’s independent position for the ‘Sael’ of his mayor’s residence. De Graeff had a clear message in mind for the ceiling painting: the ‘Ware Vrijheid’ of the Republic was only protected by the Republican regents of Amsterdam. The paintings by Gerard de Lairesse glorify the de Graeff family’s role as the protector of the Republican state, defender of ‘Freedom’. The work of art can be viewed as a visual statement opposing the return of House of Orange.[2]

In 1672, when the Orangists took power again, de Graeff lost his position as one of the key States party figure together with his nephews Pieter and Jacob de Graeff and his brother-in-law Lambert Reynst.[5] In that year, De Graeff was also attacked by the Amsterdam mob crowd at the Haarlemmerpoort.[4][7]

Marriage and children

He was married to Elisabeth Bicker van Swieten, and the couple had four children:

- Cornelis de Graeff (1650–1678) m. Agneta Deutz.

- Alida de Graeff(1 651–1738), m. Diederik van Veldhuyzen (1651–1716)

- Arnoldina de Graeff (1652–1703) m. Transisalanus Adolphus Baron van Voorst tot Hagenvoorde

- Jakob de Graeff,

Art and Lifestyle

De Graeff surrounded himself with art and beauty. He was an art collector and patron of such artists and poets like Rembrandt van Rijn, who painted his portrait, Gerard ter Borch, Govaert Flinck, Artus Quellinus[8] and Joost van den Vondel.

Van den Vondel wrote a book about De Graeffs descent and family, which was called Afbeeldingen der stamheeren en zommige telgen van de Graven, Boelensen, Bickeren en Witsens, toegewyt den edelen en gestrengen Heere Andries de Graeff, enz. met hunne portretten. Het vers Op den edelen en gestrengen Heer Andries de Graeff, Ouden Raet en Rekenmeester der Graeflijckheit van Hollant, en West-Vrieslant, nu Out-Burgermeester, en Zeeraedt t'Amsterdam[9]

At his City Palace in the Gouden Bocht ("Golden Bend"), the most prestigious part of Herengracht, he assembled a big art collection, including Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph of Rembrandt.[10]

In 1674 Andries de Graeff owned 700.000 guilders. He was one of the richest persons from the Dutch Golden Age.[11]

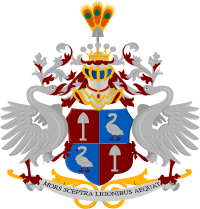

De Graeff-Von Graben connection

Before De Graeff died, he and his only son, Cornelis, became knights of the Holy Roman Empire. They said, that they descent from Wolfgang von Graben, member of the Austrian noble family House of Graben von Stein,[12] which was an apparent (or illegitimate) branch of the House of Meinhardin. That diplome dadet from 19 July 1677. Diplom loaned to Mr. Andries de Graeff, July, 19th 1677:

- "Fide digis itegur genealogistarum Amsteldamensium edocti testimoniis te Andream de Graeff non paternum solum ex pervetusta in Comitatu nostro Tyrolensi von Graben dicta familia originem ducere, qua olim per quendam ex ascendentibus tuis ejus nominis in Belgium traducta et in Petrum de Graeff, abavum, Johannem, proavum, Theodorum, avum, ac tandem Jacobum, patrem tuum, viros in civitate, Amstelodamensi continua serie consulatum scabinatus senatorii ordinis dignitabitus conspicuos et in publicum bene semper meritos propagata nobiliter et cum splendore inter suos se semper gessaerit interque alios honores praerogativasque nobilibus eo locorum proprias liberum venandi jus in Hollandia, Frisiaque occidentale ac Ultrajectina provinciis habuerit semper et exercuerit."[13]

Death

Andries de Graeff died on 30 November 1678 in Amsterdam. His tomb chapel is to be found of at the Oude Kerk.[14]

Trivia and Commons

Andries de Graeff Born: 19 OFebruary 1611 Died: 30 November 1678 | ||

| Preceded by Jonkheers Van de Werve |

Lord of the manor of Urk and Emmeloord 1660–1672 |

Succeeded by City of Amsterdam |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Andries de Graeff. |

Notes

- Andries Bickers Biography at the DBNL (dutch)

- "Triumpf of Peace". Archived from the original on 2012-03-01. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- Nederlands adelsboek 1914, p 15

- Andries de Graeffs Biography at digitale bibliothek voor de nederlandse letteren, part II (dutch)

- "Pieter Vis: Andries de Graeff (dutch)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-01. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- Whittaker and Clayton: pp. 31–2 for the art, Gleissner for the furniture and yacht. The yacht was the gift of the Dutch East India Company, according to Liverpool Museums (with model) Archived 2010-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, or the City of Amsterdam according to other sources.

- Andries de Graeffs Biography at digitale bibliothek voor de nederlandse letteren, part VII (dutch)

- Sculptur of Andries de Graeff in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (nl)

- Joost van den Vondels poem Op den edelen en gestrengen Heer Andries de Graeff, Ouden Raet en Rekenmeester der Graeflijckheit van Hollant, en West-Vrieslant, nu Out-Burgermeester, en Zeeraedt t'Amsterdam. in the book Afbeeldingen der Stamheeren en zommige telgen van de Graven, Boelensen, Bickeren en Witsens

- Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph

- Zandvliet, K. (2006) De 250 rijksten van de Gouden Eeuw: kapitaal, macht, familie en levensstijl blz. 77-79 uitg. Nieuw Amsterdam, Amsterdam, ISBN 90-8689-006-7

- Family De Graeff at the Nieuw Nederlandsch Biographisch Woordenboek, part II (dutch)

- Google books: Der deutsche Herold: Zeitschrift für Wappen-, Siegel- u. Familienkunde, Band 3, Nachrichten über die Familie de Graeff

- Google books: Joost van den Vondel about Andries de Graeff (dutch)

Literature

- Israel, Jonathan I. (1995) The Dutch Republic - Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall - 1477-1806, Clarendon Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-820734-4

- Zandvliet, Kees (2006) De 250 rijksten van de Gouden Eeuw: kapitaal, macht, familie en levensstijl blz. 93 t/m 94, uitg. Nieuw Amsterdam, Amsterdam, ISBN 90-8689-006-7

- Dudok van Heel, S.A.C.(1995) Op zoek naar Romulus & Remus. Een zeventiende-eeuws onderzoek naar de oudste magistraten van Amsterdam. Jaarboek Amstelodamum, p. 43-70.

- Burke, P. (1994) Venice and Amsterdam. A study of seventeenth-century élites.

- Graeff, P. de (P. de Graeff Gerritsz en Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek) Genealogie van de familie De Graeff van Polsbroek, Amsterdam 1882.

- Bruijn, J. H. de Genealogie van het geslacht De Graeff van Polsbroek 1529/1827, met bijlagen. De Bilt 1962-63.