Anakalang

Anakalang is a society[1] and a megalithic site on the island of Sumba, in eastern Indonesia. It is noted for its quadrangular adzes and numerous megalithic tombs.[2] The West Sumba island's best megalithic tombs are located here. They are large and well decorated and contain unusual carvings. Anakalang is the home of the "Purung Takadonga Ratu", an important Queen.[3][4]

| Anakalang | |

|---|---|

Megalithic Royal Grave Stone in Anakalang, Central Sumba. | |

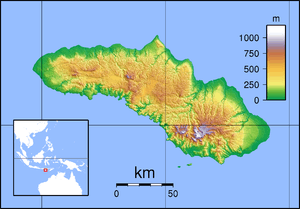

| Location | Sumba, Lesser Sunda Islands, East Nusa Tenggara , Indonesia |

| Coordinates | 9.590833°S 119.574433°E |

| Built | Unknown |

Location in Sumba | |

Geography

Anakalang is situated in a valley, the megalithic tombs spread over many villages, in the district of Anakalang. This valley is situated to the east of Waikabubak.[5] Anakalang is 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Waikabubak and is close to the main road to Waingapu;[6] buses arrive at regular intervals.[5] The district has the greatest concentration of megalithic tombs in Sumba. At Pasunga's main road, there is one of the largest tombs in Sumba.[6]

History

There is debate on the exact age of the site; radiocarbon dating has not been done to affirm this categorization. The stone schist grave with three adzes in it is inferred to be post-neolithic though no iron objects were found. The quadrangular adzes found in a small cist do not exhibit characteristics of the Neolithic age and may be post-neolithic.[2] The tradition of building megalithic tombs has continued to the present age in West Sumba. Anakalang is said to be one of the few locations where the social practices and the traditional methods followed to build megaliths can still be seen. In 1880, Umbu Dongu Ubini Mesa became the first raja of Anakalang. In 1927, Umbu Sappy Pateduk succeeded to the title.[7] Umbu Remu Samapati was the third raja, and his brother-in-law, Umbu Sulung Ibilona, succeeded him.[8]

Megalithic tombs

The megalithic grave tomb in the village of Kampung has a stone slab erected vertically. Its carved images date to 1926, taking six months to complete. The burial ceremony involved sacrifice of 150 buffaloes, and the horns of these are kept in a local house. Another tomb is on the same road about 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) away at Koboduk village. This tomb is made of concrete and tiles. It is reported to be the largest tomb in Samba. Another tomb, chiseled out of a single rock, took six years to create and is known as the Umba Saola tomb. It is 5 by 4 metres (16 by 13 ft) and 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) in thickness, weighing 70 tons. It was pulled from the hill slope where it was carved over a distance of 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) to the grave site in the Anakalang town. At the burial location there are also other tombs at the eastern side. These are upright slabs with carvings of the local king and queen with motifs of buffaloes and cockerels. Close to this tomb, the Raja’s son lives with his wife and narrates the story to visitors.[5]

Culture

Linguistically, Anakalang belongs to East Sumba, although politically and geographically it is situated within the kabupaten of West Sumba.[9] The women are mainly weavers, making baskets and mats, while the men are involved in string twining etc. Ornaments are taken care of and hidden away for ancestors.[10]

References

- Keane, Webb (1997). Signs of Recognition: Powers and Hazards of Representation in an Indonesian Society. University of California Press. p. xviii. ISBN 978-0-520-91763-7. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Simanjuntak, Truman (2006). Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective : R.P. Soejono's Festschrift. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. p. 288. ISBN 978-979-26-2499-1. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Indonesia. Direktorat Jenderal Pariwisata (1987). Destination Indonesia. Directorate General of Tourism. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Müller, Kal (1997). East of Bali: From Lombok to Timor. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-962-593-178-4. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Ver Berkmoes, Ryan (1 January 2010). Indonesia. Lonely Planet. pp. 587–. ISBN 978-1-74104-830-8. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Trade & Trade & Travel Publications (1993). Indonesia, Malaysia & Singapore Handbook. New York, NY: Prentice Hall. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Keane, Webb (4 December 2006). Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter. University of California Press. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-0-520-93921-9. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Barker, Joshua (1 July 2009). State of Authority: The State in Society in Indonesia. SEAP Publications. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-0-87727-780-4. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Webb (1997), p. xvi

- Webb (1997), pp. 247-249

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anakalang. |