Anagotus stephenensis

Anagotus stephenensis, commonly known as the ngaio weevil, is a large flightless weevil that is only found on Stephens Island in New Zealand. The ngaio weevil was discovered in 1916 by A.C. O'Connor on Stephens Island. Thomas Broun described it in 1921 as Phaeophanus oconnori after its collector. The weevils were observed at the time to be 'feeding on tall fescue and the leaves of trees'.[2]

| Ngaio weevil | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Family: | Curculionidae |

| Genus: | Anagotus |

| Species: | A. stephenensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Anagotus stephenensis G. Kuschel, 1982 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Description

This large weevil has a dark exoskeleton, covered in small hair-like coppery-brown scales. On the sides and posterior, the colouration is lighter with a prominent white streak along the centre of its thorax. It has obvious prominences on its sides and posterior. Its rostrum is as long as its thorax with a wide channel in the centre. Including the rostrum, its size ranges from 23–27 mm.[1] This weevil is nocturnal and flightless. It is similar in colouration and size and closely related to the Turbott's weevil.[3]

Distribution

The ngaio weevil has a historic range as far away as South Canterbury. The collection of elytra, heads and other body parts in seven cave deposits produced by the extinct laughing owl show it was once widespread and common. It has a relict population on Stephens Island.[2]

Habitat

The weevil is known to live on ngaio trees (Myoporum laetum), feeding on leaves, where it produces a characteristic feeding notch. The adults have also been found on the karaka tree (Corynocarpus laevigatus).[2] Larvae are thought to be woodborers of the same host tree.[4] Larvae of other members of the Aterpini tribe are mostly associated with live wood, boring into stems, leaf bases and roots.[5]

Conservation

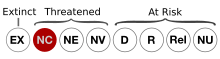

This species had its conservation status upgraded to nationally critical in 2012 due to it being found in low numbers in one location.[6] Fifteen specimens were collected by the original expedition in 1916 by A.C. O'Connor. There have not been any specimens collected since 1971 and a devoted search in 1995 found one or two specimens over five nights. This indicates a reduction in population since 1916.[2] The cause of this is likely to be the forest clearance on Stephens Island which caused a reduction in weevil habitat, when a lighthouse was built there in 1892.[7] It is possible that the side-effect of an increase in tuatara population after the removal of feral cats in 1925[8] may have been to reduce the population of the ngaio weevil.[9] The chances of a large, flightless and nocturnal beetle moving from one ngaio tree to another past numerous tuatara and surviving predation is low.[2] It is protected under Schedule 7 of The 1953 Wildlife Act, making it an offense to collect, possess or harm a specimen.[10]

References

- Broun, Thomas (30 August 1910). Descriptions of new genera and species of coleoptera. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Institute. p. 631. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Kuschel, G; Worthy, TH (1996). "Past distribution of large weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in the South Island, New Zealand, based on Holocene fossil remains title" (PDF). New Zealand Entomologist. 19: 15–19. doi:10.1080/00779962.1996.9722016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-24.

- Marris, John (2001). Beetles of Conservation Interest from the Three Kings Islands. Department of Conservation. p. 14. hdl:10182/2996.

- Kuschel, G (1982). "Apionidae and Curculionidae (Coleoptera) from the Poor Knights Islands, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 12 (3): 281. doi:10.1080/03036758.1982.10415349.

- May, Brenda (1993). "Larvae of Curculionoidea (Insecta: Coleoptera): a systematic overview" (PDF). Fauna of New Zealand. 28: 62. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Stringer, I.A.N; Hitchmough, R.A.; Leschen, R.A.B.; Marris, J.W.M.; Emberson, R.M.; Nunn, J. (2012). "The conservation status of New Zealand Coleoptera". New Zealand Entomologist. 35 (2): 91–98. doi:10.1080/00779962.2012.686311.

- Miskelly, Colin (2015-02-15). "Birds and mammals of Takapourewa / Stephens Island". Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Bellingham, Peter J.; Towns, David R.; Cameron, Ewen K.; Davis, Joe J.; Wardle, David A.; Wilmshurst, Janet M.; Mulder, Christa P.H. (2010). "New Zealand island restoration: seabirds, predators, and the importance of history" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 34 (1): 116. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Motala, Saoud; Krell, Frank-Thorsten; Mungroo, Yacoob; Donovan, Sarah E. (2007). "The terrestrial arthropods of Mauritius: a neglected conservation target" (PDF). Biodivers Conserv. 16 (10): 2876. doi:10.1007/s10531-006-9050-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- "Wildlife Act 1953". New Zealand Legislation. Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Anagotus stephenensis |

- Ngaio weevils discussed on RNZ Critter of the Week, 13 December 2019