Amy and Isaac Post

Isaac and Amy Post, were radical Hicksite Quakers from Rochester, New York, involved in the struggles for abolitionism and women's rights. Among the first believers in Spiritualism, they helped to associate the young religious movement with the political ideas of the mid-nineteenth-century reform movement.

Early life

Amy Post was born Amy Kirby on December 20, 1802, in Jericho, New York, to Joseph Kirby and Mary (Seaman) Kirby, members of the Society of Friends, also known as Quakers. The importance of humanitarian reform was embedded in Amy's early education and was the foundation for her later work as both an abolitionist and women's-rights activist.

Isaac Post was born February 26, 1798, of Long Island, New York, Quaker families. Around 1821, Isaac Post married Amy's elder sister, Hannah Kirby. In 1823 they moved to Cayuga County, New York, where he established a farm. In 1827 Hannah fell ill, and Amy joined the Posts to help care for her sister's two children. Hannah soon died, and Amy stayed on with Isaac to continue caring for the children. In 1828 Amy Kirby married Isaac Post, with whom she had four children: Jacob, Joseph, Matilda, and Willet.

That same year, radical Quakers split from the denomination, and Isaac Post and Amy Kirby joined the more radical wing, headed by Elias Hicks.[1]

After Isaac and Amy married, they moved to Rochester in 1836, where they lived on North Plymouth Avenue. In 1839, Isaac went into business as a druggist, in the Smith Arcade on Exchange Street.

Abolitionists

The couple quickly became involved in radical causes. Amy Post became an active and visible member of the Genesee Yearly Meeting of Hicksite Friends (GYM). Post, alongside her husband Isaac, dedicated much of her time to a very progressive group of Quakers who sought to give both men and women the same rights during the meetings of the Society of Friends. In 1837, Amy Post went against the desires of the Society of Friends elders, who disapproved of slavery but distrusted radical abolitionism, and signed her first "worldly" petition against slavery. In 1842, Amy and Isaac Post became two of the founders of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society (WNYASS). WNYASS was not an abolitionist group only for Quakers. Among its members were evangelical Protestants and deists as well. As an officer of the society, it was Amy Post's duty to organize fundraising fairs and group conventions. Despite the fact that the Society of Friends was a firmly anti-slavery group, the elders of the Rochester Monthly Meeting (RMM) accused Post of being too worldly in her efforts of trying to abolish slavery. Post disregarded the RMM's investigations of her "worldly" efforts and continued to be a Quaker abolitionist. She even continued distributing religious testimonies on the American Anti-Slavery Society's official letterhead. For the Posts there should be no boundary between the religious beliefs of a Quaker and political activism of an abolitionist.

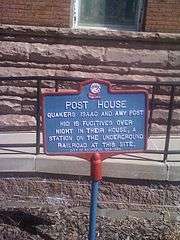

By the early 1840s, radical Quakers began to hold abolitionist meetings in the Post home, where prominent reform lecturers such as William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, and Sojourner Truth visited and spoke. Douglass became a close personal friend of the Posts who helped establish him in Rochester where he published his newspaper the "North Star".[2] Douglass and the Posts also collaborated in ferrying fugitive slaves[3] and their home served as a station on the Underground Railroad, holding as many as 20 escaped slaves at a time.

One Saturday night, after all our household were asleep, there came a tiny tap at the door, and the door was opened to fifteen tired and hungry men and women who were escaping from the land of slavery. They seemed to know that Canada, their home of rest, was near, and they were impatient, but the opportunity to cross the lake compelled their waiting until Monday early in the morning. That being settled, and their hunger satisfied, together with a comfortable and refreshing sleep, they became so elated with their nearness to perfect and lasting freedom that they were forgetful of any danger either to us, or to themselves, so that they were obliged to be constantly watched through the day to keep them from popping their heads out of the windows and otherwise showing themselves. ... The welcome Monday morning came, and after a hearty breakfast, and a lunch for dinner, they left the house, with all the stillness and quietness possible, and we soon saw them on board a Canada steamer, which was already lying at the dock; with them on board, it immediately shoved out into the middle of the stream, hoisted the British flag, and we knew that all was safe; we breathed more freely, but when we saw them standing on deck with uncovered heads, shouting their good-byes, thanks and ejaculations, we could not restrain our tears of thankfulness for their happy escape, mixed with deep shame that our own boasted land of liberty offered no shelter of safety for them.|Amy Post[4]

In 1848, the Posts also left the GYM due to pressure from elders to end their abolitionist activities as well as to help form the Yearly Meeting of Congregational Friends (YMCF), which differed greatly from the GYM in several ways. They had no ministers or elders as all people were considered equal within the YMCF. The members of YMCF would do whatever they considered necessary to end slavery, and therefore put no limit on "worldly" efforts to abolish slavery. Finally, the YMCF had no tolerance for racial or sexual discrimination. They believed that all people should be considered equal morally, religiously, and politically. The motto of the Congregational Friends was "common natures, common rights, and a common destiny."[5]

Women's rights

In 1848, Amy Post began to be involved as an organizer in the women's movement. Acting upon her beliefs in equality for women, she attended the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 in Seneca Falls, NY. She and Mary Post, her stepdaughter, were among the one hundred women and men who signed the Declaration of Sentiments, which was first presented there.

Two weeks later, she and several other women who had participated in the Seneca Falls Convention organized the Rochester Women's Rights Convention in the Post's hometown of Rochester, New York. A planning meeting chose Amy Post as temporary chair and designated a nominating committee to propose a slate of officers. The Seneca Falls Convention had followed tradition by electing a man as president of the convention. Defying tradition, the Rochester organizers proposed a woman, Abigail Bush, for that position. When the convention assembled in the Rochester Unitarian Church on August 2, Amy Post called it to order and read the suggested slate of officers. The proposal for a woman to be president of the convention was strongly opposed by some of the leaders of the women's movement who were present, fearing that women were not yet ready to take that step.[6] Bush was elected despite the opposition, making this the first public meeting of both men and women in the U. S. whose presiding officer was a woman. Amy Post continued to attend women's rights conventions, and at a convention in Rochester in 1853, she signed "The Just and Equal Rights of Women" resolution.[1]

Accompanied by Lucy Coleman, Post visited fugitive slave colonies in Canada, and attended conventions all through the North. Post became good friends with Harriet Jacobs, who she encouraged to write Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (published in 1861 under the name "Linda Brent").

Amy served the community in practical and tangible ways, such as collecting food, medical supplies, and clothing for freed slaves during the Civil War. After the War, Post became a member of both the Equal Rights Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association. In 1872, Amy Kirby Post successfully registered herself to vote, but unlike Susan B. Anthony, she was turned away at the polls and unable to cast her vote. Undaunted, Post continued her women's equality work throughout her life, and in 1885 became one of the founding members of the Women's Political Club. In 1888, Post traveled to Washington D.C. to attend the International Council of Women, the largest women's convention at that time.

Spiritualism

In 1848, the Posts took into their home the Fox sisters, Kate and Margaret, who appeared to have acquired the ability to communicate with spirits through rapping noises. They introduced the girls to their circle of radical friends, and almost all became ardent believers in the emerging religion of Spiritualism. Isaac Post himself became an acknowledged medium. His 1852 book, Voices From the Spirit World, Being Communications From Many Spirits, was presented as the spirit writings of eminent persons such as Benjamin Franklin and George Fox.[1]

Family

Isaac's brother, Joseph (30 November 1803 Westbury, New York - 17 January 1888), was also an abolitionist and had early differences with the Quakers, although they finally came around to his point of view. He encouraged Isaac T. Hopper, Charles Marriot, and James S. Gibbons when they were disowned by the Society of Friends on account of their outspoken opposition to slavery. Joseph spent his whole life in the house where he was born.[7]

Legacy

Isaac Post died in April 1872. Amy Post died January 29, 1889. They are buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York. Amy Kirby Post is remembered for her relentless fight for abolition, her extreme involvement in Women's rights activism, and her association with other well-known abolitionists and women's rights activists. Her dedication to her religious and political beliefs left a lasting impression on future women's rights activists.

Notes

- "Amy Post". Western New York Suffragists. Rochester Regional Library Council. Retrieved October 7, 2016., "Isaac Post". Western New York Suffragists. Rochester Regional Library Council. Retrieved October 7, 2016., Braude 2001

- Schmitt, Victoria Sandwhick (Summer 2005). "Rochester's Frederick Douglas Part One" (PDF). Rochester History. Rochester Public Library. v.67,no.4: 15–17. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- Schmitt, Victoria Sandwhick (Fall 2005). "Rochester's Frederick Douglas Part Two" (PDF). Rochester History. Rochester Public Library. v.67,no.4: 7–9. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- Post, Amy. "THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN ROCHESTER - Written for William F. Peck's 1884 Semi-Centennial History of Rochester(appears as Chapter XLIII, pages 458-462)". Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- "Amy Kirby Post". University of Rochester Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- Blake McKelvey (July 1948). "Women's Rights in Rochester: A Century of Progress" (PDF). Rochester History. Rochester Public Library. X (2&3): 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

References

- Braude, Ann (2001). Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21502-1.

- Britten, Emma Hardinge (1884). Nineteenth Century Miracles: Spirits and their Work in Every Country of the Earth. New York: William Britten. ISBN 0-7661-6290-7.

- Buescher, John B. (2003). The Other Side of Salvation: Spiritualism and the Nineteenth-Century Religious Experience. Boston: Skinner House Books. ISBN 1-55896-448-7.

- Carroll, Bret E. (1997). Spiritualism in Antebellum America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33315-6.

- Doyle, Arthur Conan (1926). The History of Spiritualism, volume 1. New York: G.H. Doran. ISBN 1-4101-0243-2.

- Doyle, Arthur Conan (1926). The History of Spiritualism, volume 2. New York: G.H. Doran. ISBN 1-4101-0243-2.

Hewitt, Nancy A. "Post, Amy Kirby." American National Biography Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. | url= http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00553.html |

Ripley, C. Peter. The Black Abolitionist Papers: Vol. 3, United States, 1830-1846. North Carolina: Chapel Hill University Press, 1991. Also available online at | url= https://web.archive.org/web/20080226213028/http://www.netlibrary.com/ |

Western New York Suffragists: Amy Kirby Post. Rochester Regional Library Council: 2000. | url= |

External links

- Amy Kirby Post biography on History of Women's Suffrage site

- Isaac Post biography on History of Women's Suffrage site

- The Post Family Papers Project at the University of Rochester, which contains digitized letters

- "Amy Kirby Post". Abolitionist, suffragist. Find a Grave. Jul 15, 2003. Retrieved Aug 17, 2011.

- "Isaac Post". Abolitionist. Find a Grave. Jul 15, 2003. Retrieved Aug 17, 2011.

Further reading

- "Issac and Amy Post Family papers". Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester.

- "Photograph of Amy Post from the Amy and Isaac Post Family papers". Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester.