Amtrak Standard Stations Program

The Amtrak Standard Stations Program was an effort by Amtrak to create a standardized station design.[1] Amtrak believed that these station designs would enhance Amtrak's corporate image.[1] This effort was formally launched in 1978.[2]

Background

The program was spurred by the need for Amtrak to build new stations. As a new entity, the company did not initially have any of its own facilities – stations and depots were inhereted from its constituent railroads. In many locations, existing station buildings were in disrepair.[1] In other locations, route realignments, ownership conflicts, or a lack of existing facilities necessitated the construction of new station houses.[1] Additionally, existing grand terminals in many large cities had more capacity than Amtrak's requirements and were expensive to retain. These reasons and others prompted the effort to provide those locations with more modern and appropriately sized facilities.[1]

The first new station Amtrak constructed itself was Cincinnati River Road in 1973,[3] however that is not of a standard design. Early attempts by Amtrak to create a modest "modern" station designs include the Richmond Staples Mill Road station (opened in 1975) and Cleveland Lakefront station (opened in 1977). Amtrak president Paul H. Reistrup expressed a desire for Amtrak stations to look familiar in each locality.[3]

Amtrak would formally outline its Standard Stations Program in its 1978 Standard Stations Program Executive Summary.[2] The program was intended to amplify a sleek, modern image.[1] It was also intended foster a unified corporate identity through a consistent "look" and branding, with each standard station utilizing not only one of several similar station building designs, but also the same interior and exterior finishes, signage, and seating.[1] The program's manual outlined the reasoning of for such efforts.

Amtrak is not a railroad of the past, but rather, a transportation system of the present and future. We must compete with the airlines and their jetports, the interstate highway system and its convenient and modern service stations and restaurants, and inter-city busses with their new or upgraded terminals.

Our passenger stations are also our only permanent presence in most communities…Amtrak’s public image can be greatly enhanced, or easily destroyed by our facilities.

Unlike the railroads of the past, we have no place for grandiose, monumental stations that cannot be financed by our projected revenues.

— Amtrak Standard Stations Program Manual[1]

Standard designs were seen as cost efficient as they would eliminate design costs that would otherwise be incurred with each and every station were they uniquely designed and would also expedite construction.[1][3]

Station designs

The station structures were intended to be functional, flexible, and cost-efficient.[1] With spikes in ridership during the 1970s due to oil shortages, there was a perceived potential for permanent ridership gains.[1] Therefore, Amtrak designed the stations to be easily expanded.[1] End walls of the stations were designed to be able to be removed in order to build additions without incurring disruptions to the functioning of the stations.[1][3]

Designs were mostly rectangular, and all except the largest model were one story.[1][3] Walls were to be built of either textured, precast concrete panels, split concrete block or brick in what was described as a “play of bronze and tan” colors.[1][3] A prominent cantilevered, flat black metal roof was to sit atop the buildings, with deep eaves to protect passengers from bad weather.[1][3][4] Stations had floor-to-ceiling windows.[1][4] Often, the top edge of the walls had a band of clerestory windows, which from a distance provided an optical illusion that the roof was floating above the station.[1] The square footage and amenities of stations were to be determined by what their peak hour passenger count was.[1]

Five initial standard station design models were presented with varying ideal sizes and intended capacities:[1]

- Type 300A[1]

- Type 150B[1]

- a 8,220-square-foot (764 m2) station for a peak count of 150-300 passengers, on a five acres (2 ha) parcel

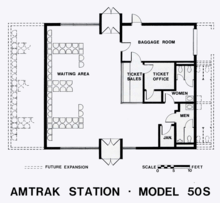

- Type 50C and 50S[1]

- a 1,920-square-foot (178 m2) station for a peak count of 50-150 passengers, on a four acres (1.6 ha) parcel

- Type 25D[1]

- a 1,150-square-foot (107 m2) station for a peak count of 25-50 passengers, on a two acres (0.8 ha) site

- Type E[1]

- an unmanned station, 240 square feet (22 m2) for a peak count of less than 25 passengers, ideally situated on a one acre (4,000 m2) parcel

Outcome

Amtrak constructed standard stations in the 1970s and 1980s,[1] but ultimately built relatively few of them.[3] Strapped for funds, it instead gravitated towards either building even cheaper modular stations or seeking local funding for station development, in some cases even cooperating with private developers.[3] Many "stations" opened in the 1980s and 1990s were very minimal, sometimes lacking any facilities besides a platform and appropriate signage or only featuring simple bus stop-style platform shelters. Many of the standard stations have been replaced with more modern intermodal facilities or by restored previous historic stations throughout the 2000s and 2010s. As of 2016 the documentation is still referenced when necessary in planning or constructing new stops.[5]

List of standard stations

| Station Name | City | Design | Opened | Closed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albany–Rensselaer | Rensselaer, New York | 1980 | 2002 | demolished 2010 | |

| Anaheim–Stadium | Anaheim, California | 1984 | 2014 | Rebuilt and renamed "Anaheim Regional Transportation Intermodal Center" | |

| Ann Arbor | Ann Arbor, Michigan | 1983 | |||

| Buffalo–Depew | Depew, New York | 1979 | |||

| Canton–Akron | Canton, Ohio | 50C[6] | 1978 | 1990 | [7] |

| Carbondale | Carbondale, Illinois | 1981 | |||

| Dearborn | Dearborn, Michigan | 1979 | c. 2011 | demolished, replaced with current John D. Dingell Transit Center | |

| Flint | Flint, Michigan | 1989 | |||

| Grand Forks | Grand Forks, North Dakota | 1982 | |||

| Hammond–Whiting | Hammond, Indiana | 1982 | |||

| Huntington | Huntington, West Virginia | 1983 | |||

| Miami | Miami, Florida | 300A | 1978 | pending closure | |

| Midway | Saint Paul, Minnesota | 300A | 1978 | 2014 | |

| Normal | Normal, Illinois | 1990 | 2012 | ||

| Omaha | Omaha, Nebraska | 1983 | |||

| Rochester | Rochester, New York | 150B[6] | 1978 | 2015 | demolished, replaced with Louise M. Slaughter Rochester Station |

| Schenectady | Schenectady, New York | 1979 | 2017 | demolished, replaced with current facility | |

| Tacoma | Tacoma, Washington | 1984 | pending closure | ||

Others

- Cleveland Lakefront station – prototype opened in 1977

- Du Quoin station – built in the late 1980s, shares characteristics with standard stations

- Richmond, California station – constructed in 1978, closed in 1997, shares characteristics with standard stations

- Richmond Staples Mill Road station – prototype opened in 1975

See also

- List of Amtrak stations

- Amshack, derisive term occasionally applied to, among other stations, those of this sort

References

- ""The Amtrak Standard Stations Program". Amtrak. 4 March 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Standard Stations Program Executive Summary. National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Office of the Chief Engineer). 1978.

- Sanders, Craig (May 11, 2006). "Amtrak in the Heartland". Indiana University Press. p. 270.

- "New Schenectady Station Added to Amtrak's Great Stations List". Schenectady Metroplex Development Authority. 9 November 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- "Memorandum of understanding among the transportation agency for Monterey County, the City of Salinas, and Monterey-Salinas Transit District, regarding the Salinas Intermodal Transportation Center" (PDF). Transportation Agency for Monterey County. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Rochester Gets New Station, "Amtrak Week" Proclaimed By Mayor". Amtrak News. 5 (8). August 1978. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Canton Station Opens, City Officials Praise Amtrak". Amtrak News. Amtrak. 5 (7). July 1978.