Ambrogio Lorenzetti

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Italian pronunciation: [amˈbrɔːdʒo lorenˈtsetti]; c. 1290 – 9 June 1348)[1] or Ambruogio Laurati was an Italian painter of the Sienese school. He was active from approximately 1317 to 1348. He painted The Allegory of Good and Bad Government in the Sala dei Nove (Salon of Nine or Council Room) in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico. His elder brother was the painter Pietro Lorenzetti.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1285/1290 |

| Died | 9 June 1348 (aged 57–63) Siena |

| Nationality | Republic of Siena |

| Known for | Painting, fresco |

Notable work | Allegory of good government, Allegory of bad government |

| Movement | Gothic |

Biography

Lorenzetti was highly influenced by both Byzantine art and classical art forms, and used these to create a unique and individualistic style of painting. His work was exceptionally original. Individuality at this time was unusual due to the influence of patronage on art. Because paintings were often commissioned, individualism in art was infrequently seen. It is known that Lorenzetti engaged in artistic pursuits that were thought to have their origins during the Renaissance, such as experimenting with perspective and physiognomy, and studying classical antiquity.[2] His body of work clearly shows the innovativeness that subsequent artists chose to emulate.

His work, although more naturalistic, shows the influence of Simone Martini. The earliest dated work of the Sienese painter is a Madonna and Child (1319, Museo Diocesano, San Casciano). His presence was documented in Florence up until 1321. He would return there after spending a number of years in Siena.[3]

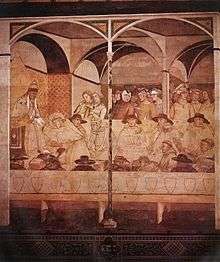

Later he painted The Allegory of Good and Bad Government. The frescoes on the walls of the Room of the Nine (Sala dei Nove) or Room of Peace (Sala della Pace) in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico are one of the masterworks of early Renaissance secular painting. The "nine" was the oligarchal assembly of guild and monetary interests that governed the republic. Three walls are painted with frescoes consisting of a large assembly of allegorical figures of virtues in the Allegory of Good Government.[4] In the other two facing panels, Ambrogio weaves panoramic visions of Effects of Good Government on Town and Country, and Allegory of Bad Government and its Effects on Town and Country (also called "Ill-governed Town and Country"). The better preserved "well-governed town and country" is an unrivaled pictorial encyclopedia of incidents in a peaceful medieval "borgo" and countryside.

The first evidence of the existence of the hourglass can be found in the fresco, Allegory of Bad Government and Its Effects on Town and Country.

Like his brother, he is believed to have died of bubonic plague in 1348.[5] Giorgio Vasari includes a biography of Lorenzetti in his Lives.

Selected works

Annunciation, 1344 Lorenzetti's final piece, telling the story of the Virgin Mary receiving the news from the Angel about the coming of baby Jesus, contains the first use of clear linear perspective. Though it is not perfect, and the gold background that is traditional for the time renders a flat feeling, the diagonals created on the floor do create depth.

Madonna and Child, 1319

In Madonna and Child, there is a clear debt to Byzantine art. The image of the Madonna is noted for its frontality, which is a typical characteristic of Byzantine art.[2] The Madonna faces the viewer, as the Child gazes up at her. Though not as emotionally intense as subsequent Madonnas, in Lorenzetti's Madonna and Child, the Virgin Mary belies a subtle level of emotion as she confronts the viewer. This difference could be attributed to the patron's stylistic wishes for Madonna and Child, or could indicate Lorenzetti's evolution of style. But, even in this early work, there is evidence of Lorenzetti's talent for conveying the monumentality of figures, without the application of chiaroscuro.[2] Chiaroscuro was often used to subtle effect in Byzantine art to depict spatial depth. Ambrogio instead used color and patterns to move the figures forward, as seen in Madonna and Child.

Investiture of Saint Louis of Toulouse, 1329

In this fresco, St. Louis is being greeted by Pope Boniface VIII as he is granted the title of Bishop of Toulouse. It was one in a series of frescoes painted with his brother, Pietro Lorenzetti, for Saint Francis of Assisi.[6] This fresco is particularly well known for its realistic sense of depth within an architectural environment, due to Lorenzetti's compellingly rendered three-dimensional space. Moreover, his figures are positioned in a very natural and familiar manner, introducing an awareness of naturalism in art. Lorenzetti's command of spatial perspective is thought to prefigure the Italian Renaissance. This fresco also shows his talent for depicting emotion, as we see on King Charles II’s face during the king’s witness to his son’s rejection of material goods and power.[7] Such attention to detail possibly indicates an intellectual curiosity. Giorgio Vasari, in Lives of the Most Excellent, Painters, Sculptors and Architects wrote of Lorenzetti's intellectual abilities, saying that his manners were "more those of a gentleman and philosopher than those of an artist".[8]

Maestà, 1335

In his Maestà, completed in 1335, his use of allegory prefigures Effects of Bad Government in the City. Allegorical elements reference Dante,[9] indicating an interest in literature. Additionally, this might point to the beginnings of vernacularization of literature at this time, a precursor to humanist ideas. In Maestà, Lorenzetti followed the artistic tradition set by other Sienese painters like Simone Martini but adds an intense maternal bonding scene to Maestà, which was unusual in contemporary Sienese art. In the painting, the Virgin gazes at her child with intense emotion as he grasps her dress, returning her gaze. By personalizing the Virgin Mary in this way, Lorenzetti has made her seem more human, thus creating a profound psychological effect on the viewer. This highlights the increasing secularity in Sienese art at this time, of which Lorenzetti was a leading proponent, through the uniqueness of his painting style. The crowd of saints depicted with the Virgin is a Byzantine artistic tradition, used to indicate an assemblage of witnesses.[9] As such, Lorenzetti's art could be seen as a transition between Byzantine and Renaissance styles of art. Lorenzetti's interest in classical antiquity can be seen in Maestà, particularly in the depiction of Charity.[9] In his memoirs, I Commentarii, the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti mentions Lorenzetti's interest in an antique statue uncovered during an excavation in Siena at the time, attributed to the Greek sculptor, Lysippus.[10]

References

- Frank N Magill; Alison Aves (1 November 1998). Dictionary of World Biography. Routledge. pp. 595–. ISBN 978-1-57958-041-4.

- Chiara Frugoni, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, (Florence: Scala Books, 1988), 37.

- Casu, Franchi, Franci. The Great Masters of European Art. Barnes & Noble, Inc., 2006. Page 34, Retrieved November 25, 2006.

- Early Modern Literary Studies. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- "Effects of Good Government in the city". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- S. Maureen Burke, “The Martyrdom of the Franciscans by Ambrogio Lorenzetti”, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 65: H.4 (2002): 467.

- Diana Norman, “ ‘Little Desire for Glory’: the Case of Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti”, The Changing Status of the Artist, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 41.

- Enzo Carli, Sienese Painting, (New York: Scala Books, 1983), 38.

- Chiara Frugoni, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, (Florence: Scala Books, 1988), 48.

- Schlegel, Ursula (March 1970). "The Christchild as Devotional Image in Medieval Italian Sculpture: A Contribution to Ambrogio Lorenzetti Studies". The Art Bulletin. 52 (1): 1–10. doi:10.2307/3048674. JSTOR 3048674. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

Further reading

- Bowsky, William M. (1962). "The Buon Governo of Siena (1287-1355): A Mediaeval Italian Oligarchy". Speculum. 37 (3): 368–381. doi:10.2307/2852358. JSTOR 2852358.

- ——— (1967). "The Medieval Commune and Internal Violence: Police Power and Public Safety in Siena, 1287-1355". American Historical Review. 73 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/1849025. JSTOR 1849025.

- Bowsky, William M. (1981). A Medieval Italian Commune; Siena Under The Nine, 1287-1355. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04256-8.

- Debby, Nirit Ben-Aryeh (2001). "War and Peace: the description of Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Frescoes in Saint Bernardino's 1425 Siena Sermons". Renaissance Studies. 15 (3): 273–286. doi:10.1111/1477-4658.00370.

- Feldges-Henning, Uta (1972). "The Pictorial Programme of the Sala della Pace: A New Interpretation". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 35: 145–162. doi:10.2307/750926. JSTOR 750926.

- Frugoni, Chiara (1988). Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Florence, Italy: Scala, Istituto Fotografico Editoriale. ISBN 978-0-935748-80-2.

- ——— (1991). A Distant City; Images of Urban Experience in the Medieval World. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04083-7.

- Greenstein, Jack M. (1988). "The Vision of Peace: Meaning and Representation in Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Sala Della Pace Cityscapes". Art History. 11 (4): 492–510. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.1988.tb00320.x.

- Norman, Diana (1997). "Pisa, Siena, and the Maremma: a neglected aspect of Ambrogio Lorenzetti's paintings in the Sala dei Nove". Renaissance Studies. 11 (4): 311–341. doi:10.1111/j.1477-4658.1997.tb00025.x.

- Polzer, Joseph (2002). "Ambrogio Lorenzetti's 'War and Peace' Murals Revisited: Contributions to the Meaning of the 'Good Government Allegory'". Artibus et Historiae. 23 (45): 63–105. doi:10.2307/1483682. JSTOR 1483682.

- Prazniak, Roxann (2010). "Siena on the Silk Roads: Ambrogio Lorenzetti and the Mongol Global Century, 1250–1350". Journal of World History. 21 (2): 177–217. doi:10.1353/jwh.0.0123.

- Rubinstein, Nicolai (1958). "Political Ideas in Siense Art: The Frescoes by Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Taddeo di Bartolo in the Palazzo Pubblico". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 21 (3/4): 179–207. doi:10.2307/751396. JSTOR 751396.

- Skinner, Quentin (1989). "Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher". In Belting, Hans; Blume, Dieter (eds.). Malerei und Stadtkultur in der Dantezeit: die Argumentation der Bilder (in German). Munich: Hirmer. pp. 85–103. ISBN 978-3-7774-5030-8.

- Southard, Edna Carter (1979). The Frescoes in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico, 1289-1539: Studies in Imagery and Relations to other Communal Palaces in Tuscany. New York: Garland. ISBN 978-0-8240-3967-7.

- Starn, Randolph (1987). "The Republican Regime of the "Room of Peace" in Siena, 1338-40". Representations. 18 (18): 1–32. doi:10.2307/3043749. JSTOR 3043749.

- ——— (1994). Ambrogio Lorenzetti; The Palazzo Pubblico, Siena. New York: George Braziller. ISBN 978-0-8076-1313-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ambrogio Lorenzetti. |