Amatory fiction

Amatory fiction is a genre of British literature that became popular during the late 17th century and early 18th century, approximately 1660-1730.[1] It was often spread throughout coteries, published while trying to remain true to the writer's vision without criticism. Amatory fiction predates, and in some ways predicts, the invention of the novel and is an early predecessor of the romance novel. Indeed, many themes of the contemporary romance novel were first explored in amatory fiction. The writing of amatory fiction work was dominated by women, and it was considered to have mainly female readers; but it is assumed that men read these novels as well. As its name implies, amatory fiction is preoccupied with sexual love and romance. Most of its works were short stories.

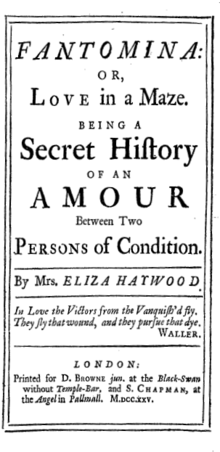

The three most prominent amatory fiction writers were: Eliza Haywood (who wrote Love in Excess; Or, The Fatal Enquiry and Fantomina: Or, Love in a Maze, as well as over 70 other published works); Delarivier Manley, (author of The Lost Lover (play) and Almyna: or, The Arabian Vow. A Tragedy) and Aphra Behn (who wrote The History of the Nun and "To the Fair Clarinda, Who Made Love to Me, Imagined More than Woman",[2] and one of her most popular works "The Disappointment", which is a tale about a sexual encounter, written from a females point of view, could possibly be about male impotence). Together, these writers were known as "the fair triumvirate of wit", a phrase coined by Rev. James Sterling,[3] though their reputation for scandalous writing caused some to call them the "naughty triumvirate."[4]'

Themes of amatory fiction

Narrowly defined, amatory fiction challenges formulaic genre which typically depicts an innocent, trusting woman being deceived by a self-serving, lustful man, by reversing the gender specific roles. For example, in Fantomina, by Eliza Haywood, the nameless protagonist is a noble born woman who changes her appearance to seduce the male Beauplaisir numerous times.[1] For the women of amatory fiction, love typically ends in misery.

A form of feminism

Authors of amatory fiction had a tendency to use their novellas as a commentary on women's roles in society, and how they were being treated. There are many instances where the use of sarcasm highlights the sentiment the author was trying to get across to the audience. Another popular, and similar, writing tactic was called swerve, which involved the author being sarcastic about how they were viewed to be inferior, as to not upset the male critics. These writers often detailed extramarital affairs, and promoted strong themes of scandal, and sexual promiscuity.

While an observer would immediately identify a focus on sentimental love and the erotic, there is an underlying motivation to present the woman in an entirely different light. Instead of sentimentality and the abundance of romantic elements, there is an identifiable desire to depict women who want fulfillment of their own sexual desire as opposed to merely serving the pleasure of men. For example, a writer of amatory fiction would create a female character who demands more from friendship and pursues personal satisfaction in her relationships. For a time, this was branded as sentimentality and romantic thinking.[5] However, later years would recognize this as a way in which women started to break away from the oppressive tactics of male domination. There are those who also link amatory fiction to the concept of the female Bildungsroman, which promoted a female character's development "especially its interest in portraying a form of female power that is viable even in a society where women were allowed only limited control over their own lives." [6]

Although amatory fiction was originally excluded from "rise of the novel[7]" narratives, traditionally written by men, contemporary scholars conclude that these works are not merely precursors to the novel, but novels in their own right. These amatory works were some of the only places women could speak for themselves, express their feelings of oppression, and share their experiences.[1]

Some works of amatory fiction were considered immoral by contemporary standards, and allowed their characters to commit scandalous love affairs without being "punished" based on themes of Christian, social, legal or other forms of poetic justice.

Notes

- Backscheider, Paula R.; Richetti, John J. (1996-01-01). Popular Fiction by Women, 1660-1730: An Anthology. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198711360.

- "To the Fair Clarinda, Who Made Love to Me, Imagined More Than Woman - a poem by Aphra Behn". www.poetry-archive.com. Retrieved 2016-10-13.

- Anderson, Paul Bunyan (1936). "Mistress Delariviere Manley's Biography". Modern Philology. The University of Chicago Press. 33. JSTOR 434067.

- Toni O'Shaughnessy Bowers, "Sex, Lies, and Invisibility: Amatory Fiction from the Restoration to Mid-Century," The Columbia History of the British Novel, Ed. John Richetti, Columbia UP, 1994, 51.

- Backscheider, Paula (2013). Elizabeth Singer Rowe and the Development of the English Novel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9781421408422.

- Ellis, Lorna (1999). Appearing to Diminish: Female Development and the British Bildungsroman, 1750-1850. London: Bucknell University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0838754112.

- Carnell, R. (2006-08-19). Partisan Politics, Narrative Realism, and the Rise of the British Novel. Springer. ISBN 9781403983541.

Further reading

- Ballaster, R. (1998). Seductive Forms: Women's Amatory Fiction from 1684 to 1740. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818477-5.

- Benedict, Barbara M. (1998) 'The curious genre: Female inquiry in amatory fiction.' Studies in the Novel (1998): 194-210.

- Bowers, Toni O'Shaughnessy (1994). 'Sex, Lies, and Invisibility: Amatory Fiction from the Restoration to Mid-Century'. In The Columbia History of the British Novel. Ed. John Richetti et al. New York: Columbia UP, 50-72. ISBN 0-231-07858-7.

- Hultquist, A. (2008). 'Equal Ardor: Female Desire, Amatory Fiction, and the Recasting of the Novel, 1680–1760'. ProQuest.