Amara War Cemetery

The Amara War Cemetery is a First World War British military cemetery in Amara, now known as Amarah, southern Iraq, that is the responsibility of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). It contains more than 4,600 graves including three recipients of the Victoria Cross but is now in poor condition as the CWGC have not been able to work in Iraq since 1991.

Location

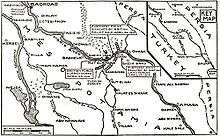

The cemetery is located immediately to the south of one of the branches of the River Tigris where it splits at Amarah in an area that was seized by the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force during the First World War.[1] Amarah became a major hospital centre with medical detachments on both sides of the river and seven general hospitals. The cemetery is now the responsibility of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.[2]

Burials

The cemetery contains 4,621 burials from the First World War, of which more than 3,000 were interred after the end of the war. Only 3,696 of the dead have been identified. In 1933, the grave headstones were removed after it was found that they were being damaged by salts in the soil and a memorial wall erected instead with the names of the dead engraved upon plaques.[2]

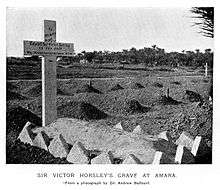

Graves at Amara include the surgeon Sir Victor Horsley, and Victoria Cross recipients Sidney William Ware,[3] Edgar Christopher Cookson,[4] and Edward Elers Delaval Henderson.[5] Captain Alfred Wallace Harvey of the Royal Army Medical Corps, who was shot by a sentry from his own side, is also buried at Amara.[6]

Immediately to the south of the British cemetery is the Amara (Left Bank) Indian War Cemetery which contains the graves of more than 5,000 Indian soldiers killed during the Mesopotamian campaign.[7]

Condition

In 2003, the BBC reported that the cemetery was in the care of Hassan Hatif Moson who said that he took the keeper's job in 1977 and had maintained the cemetery despite threats from Ba'ath Party officials.[8] He said he had not been paid since 1991 but received support from Baroness Nicholson of Winterbourne, founder of the charity AMAR. The CWGC, however, said that Mosa has never been in their employ but that they would be appointing a caretaker for the cemetery.[9]

In 2014, commentating on the run-down condition of the cemetery, Iraqi sources urged that the cemetery be restored after neglect that they blamed on the local government and the fact that the cemetery was not recognised as part of Iraq's heritage. Commentators argued that it was an important site in the history of the local area and a monument to the resistance of local tribesmen to British occupation and so should be preserved.[10]

In April 2016, Martin Fletcher of The Times, reporting from Amarah, wrote that the cemetery had seriously deteriorated, with plaques falling from the memorial wall and the Cross of Sacrifice smashed. The perimeter wall and other cemetery infrastructure are also damaged. A man who described himself as the caretaker reported the cross being blown up one night in 2006. The CWGC commented that they had not been able to work in Iraq since 1991, but the cemetery would be restored when conditions allowed.[9]

See also

References

- Reassessing consequences of occupation in Iraq. Wassim Bassem, Al-Monitor, 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- AMARA WAR CEMETERY. Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Sidney William Ware VC. The Comprehensive Guide to the Victoria & George Cross. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- Edgar Christopher Cookson VC, DSO. The Comprehensive Guide to the Victoria & George Cross. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- Edward Elers Delaval Henderson VC. The Comprehensive Guide to the Victoria & George Cross. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- Captain Alfred Wallace Harvey Royal Army Medical Corps. Archived 2016-04-14 at the Wayback Machine Winkleigh Heroes. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- Chhina, Rana. (2014) Last Post: Indian War Memorials Around the World. Delhi: Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research, United Service Institution of India. p. 218. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3

- Lost British graveyard found in Iraq. BBC News, 18 April 2003. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- British war graves left to crumble in the dust, Martin Fletcher, The Times, 25 April 2016, pp. 14–15.

- مقبرة-الانكليز-في-العمارة-حافظت-على Almada Press. 9 September 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amara War Cemetery. |