Aluminum joining

Aluminum alloys are often chosen due to their high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, low cost, high thermal and electrical conductivity. There are a variety of techniques to join aluminum including mechanical fasteners, welding, adhesive bonding, brazing, soldering and friction stir welding (FSW), etc. Various techniques are used based on the cost and strength required for the joint. In addition, process combinations can performed to provide means for difficult to join assemblies and to reduce certain process limitations.

Mechanical fasteners

.jpg)

A simple and cheap method to join aluminum is using mechanical fasteners (i.e. bolts and nuts). Normally a hole is drilled into the base material and a fastener is placed inside. This type of joiner requires some type of overlapping material for a joint to be made. Aluminum rivets or bolts and nuts can be used; however, high-stress applications would require higher strength fastener material such as steel. This could lead to galvanic corrosion of different materials which have varying electrochemical potential. Significant corrosion would weaken the assembly over time and possibly lead to failure. In addition, different materials could result in thermal fatigue cracking from differing coefficients of thermal expansion. As the assembly is repeatedly heated stresses can build up and enlarge the mounting hole. A commonplace mechanical fasteners are used is riveting of aluminum panels on airplane exteriors.[1]

Adhesive bonding

Aluminum can be joined with a variety of adhesives. Aluminum may require some level of surface preparation and passivation to remove any unwanted chemical from the surface. Passivation could be as simple as rubbing alcohol or ultrasonic cleaning. Before bonding, a dry fit should be conducted to confirm proper fitting of the components. Adhesives may require heat, pressure, or both during curing; however, the adhesive application should be conducted per the adhesive manufacturer's instructions.[2]

Surface preparation

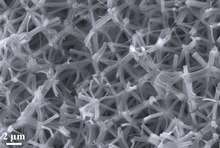

In order for a proper adhesive bond, some surface preparation is necessary. A surface cleaning to remove any impurities is made. The surface of the parts to be joined may be roughened with an abrasive such as sandpaper. This provides interlocking surface asperities and increases surface area for bonding. A chemical treatment may also be needed to increase the surface energy of the adherent and remove the oxide layer. Aluminum oxide is weakly bonded to the underlying aluminum metal and without removal, the adhesive joint is dramatically weakened. Oxides layers can separate from the metal substrate and is a key principle for adhesive failure theory, Bikerman weak boundary layer. One way to strength the oxide layer and prevent oxide to substrate failure is to anodize the material. Anodizing creates a strong hexagonal oxide layer with additional surface area for adhesive joining.

Type of adhesives

Adhesive selection can be dictated based on cost, strength and needed ductility. Hobbyist commonly uses cyanoacrylate (super glue), epoxy, or JB Weld. Silicone may also be used in an application in which waterproofing is needed.

Welding

Most aluminum alloys can be joined by welding together; however, certain aircraft grade aluminum and other special alloys are unweldable using conventional methods. Aluminum is commonly welded with gas metal arc welding (GMAW) and gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW). Due to aluminum's oxide layer, a positive polarity is needed break up the surface to ensure a proper weld. Alternating current (AC) is also used to allow the benefits of a negative polarity which provides penetration and enough positive polarity for a containment free weld. For more details on welding parameters structural aluminum welding codes can be found in AWS D1.2.[3] Aluminum welding typically creates a softened region in the weld metal and heat affected zone. Additional heat treatments may be needed to obtain an acceptable material for an application.[4] Industrial welding is also commonly found in joining aluminum: friction stir welding, laser welding, and ultrasonic welding are some of the many processes used.

Brazing and soldering

Aluminum can be brazed or soldered to almost any material including concrete, ceramics, or wood. Brazing and soldering can be applied manually or through an automated technique. Manual aluminum brazing can be difficult due to no observable color change before melting. Similar to other techniques, aluminum's strong oxide can prevent proper bonding. Strong acids and bases can be used to weaken the oxide or aggressive fluxes may be used. Brazing alloys for aluminum must have a relatively low melting temperature which is below aluminum's melting temperature (660 °C). In addition, aluminum alloys with high magnesium content can "poison" fluxes and depress the melting temperature which can result in a weak joint. In some cases, the aluminum parts can be clad with a different material and brazed with a more common technique and filler material. Brazed joints require overlapping of parts. The amount of overlap can greatly affect the strength of the joint.[5]

Friction stir welding

Friction stir welding is a solid-state joining process that uses a non-consumable tool to join two facing workpieces without melting the workpiece material.[6][7] Heat is generated by friction between the rotating tool and the workpiece material, which leads to a softened region near the FSW tool. While the tool is traversed along the joint line, it mechanically intermixes the two pieces of metal, and forges the hot and softened metal by the mechanical pressure, which is applied by the tool, much like joining clay, or dough.[7] It was primarily used on wrought or extruded aluminium and particularly for structures which need very high weld strength.

References

- Bonenberger, Paul R. (2005). The First Snap-Fit Handbook. 6915Valley Avenue,Cincinnati, Ohio 45244-3029, USA: Hanser Gardner Publications, Inc. ISBN 1-56990-388-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Pocius, Alphonsus V. (2012). Adhesion and Adhesives Technology: An Introduction. 6915 Valley Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio 45244-3029, USA: Hanser Publications. ISBN 978-3-446-43177-5.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Society, American Welding. "AWS D1.2, Structural Welding Code – Aluminum : Certification : American Welding Society". www.aws.org. Retrieved 2018-04-03.

- Lippold, John C. (2015). Welding Metallurgy and Weldability. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 978-1-118-23070-1.

- American Welding Society (AWS) C3 Committee on Brazing and Soldering (2011). BRAZING HANDBOOK, 5th EDITION. 550 N.W. LeJeune Road, Miami, FL 33126: American Welding Society. ISBN 978-0-87171-046-8.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Li, Kun; Jarrar, Firas; Sheikh-Ahmad, Jamal; Ozturk, Fahrettin (2017). "Using coupled Eulerian Lagrangian formulation for accurate modeling of the friction stir welding process". Procedia Engineering. 207: 574–579. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.10.1023.

- "Welding process and its parameters - Friction Stir Welding". www.fswelding.com. Retrieved 2017-04-22.