Alto Rio Negro Indigenous Territory

The Alto Rio Negro Indigenous Territory (Portuguese: Terra Indígena Alto Rio Negro) is an indigenous territory in the northwest of the state of Amazonas, Brazil. It is in the Amazon biome, and is mostly covered in forest. A number of different ethnic groups live in the territory, often related through marriage, with a total population of over 25,000. There is a long history of colonial exploitation and effective slavery of the indigenous people, and then of attempts to suppress their culture and "civilize" them. The campaign to gain autonomy culminated in creation of the reserve in 1998. The people are generally literate, but health infrastructure is poor and there are very limited economic opportunities.

| Alto Rio Negro Indigenous Territory | |

|---|---|

| Terra Indígena Alto Rio Negro | |

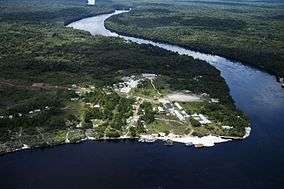

Assunção do Içana | |

| |

| Nearest city | São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Amazonas |

| Coordinates | 1°23′24″N 68°09′12″W |

| Area | 7,999,000 ha (30,880 sq mi) |

| Designation | Indigenous territory |

| Created | 15 April 1998 |

| Administrator | FUNAI |

Location

The Alto Rio Negro Indigenous Territory is in the northwest of the state of Amazonas. It has an area of 7,999,000 hectares (19,770,000 acres).[1] It is divided between the municipalities of Japurá and São Gabriel da Cachoeira, and covers 68% of the latter municipality. It borders Colombia to the north and west.[1]

To the south the territory adjoins the Rio Apapóris and the Médio Rio Negro I indigenous territories. To the east it adjoins the Cué-cué/Marabitanas Indigenous Territory.[1] Other indigenous territories in the Alto Rio Negro region are the Médio Rio Negro II, Balaio and Rio Tea. Together the territories cover more than 11,500,000 hectares (28,000,000 acres) of the municipalities of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Santa Isabel do Rio Negro, Barcelos and Japurá. As of 2016 all had been homologated by the federal government apart from Cué-Cué / Marabitanas, which had only been declared.[2]

The Alto Rio Negro Indigenous Territory is 96.24% in the Rio Negro basin and 3.6% in the Japurá River basin. The Rio Negro defines the southwest boundary. Major tributaries of the Rio Negro in the reserve include the Xié, Içana and Uaupés rivers. The Tiquié River is an important tributary of the Uapés.[1]

History

Colonial era

From the mid-17th century there was a growing shortage of indigenous labor in the lower Amazon, in part due to smallpox epidemics, and settlers began raiding the upper Amazon and the Rio Negro to capture slaves, massacring those who resisted. The Portuguese reached the upper Rio Negro in the first half of the 18th century and its main tributaries such as Uaupés, Içana and Xié. The Carmelites set up settlements on the Upper Rio Negro near the present city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira. It is estimated that in this period 20,000 Indians were captured to work on the farms of Belém and São Luís, Maranhão.[3]

In the second half of the 18th century the Portuguese government under the Marquis of Pombal removed the secular power of the missionaries, replacing them by civil or military authorities, and raised the more prosperous settlements to the status of villages or cities with Portuguese names, usually that of a saint.[3] The years that followed saw growing military control of the region, forced labor for colonists and missionaries, depopulation due to forced migration and epidemics, occasional violent revolts and a variety of religious movements.[4] Many of the indigenous people moved to the less accessible upper courses of the rivers.[5]

20th century

In the 20th century there was steady decline in extractive exploitation. Missionary centers were established among the indigenous people, and provided a measure of protection against the traders. North American evangelical missionaries of the New Tribes Mission led by Sophie Muller entered the region in the 1940s. The Salesian (Catholic) missions continued to provide most of the infrastructure of sanitation, education and commerce.[5]

In the 1970s the federal government launched the National Integration Plan to integrate the Amazon region with the rest of the country, and FUNAI posts were installed in the Upper Rio Negro region.[5] Army frontier units were also moved into the region. A gold rush invaded the Serra do Traíra and the upper Içana region in the 1980s causing rapid growth of São Gabriel, which doubled in size in less than ten years. Another factor in the growth of São Gabriel was that families moved to the city during the school year due to the closure of the missionary boarding schools. A move by indigenous groups to regain control of their traditional territories developed in the 1990s.[6]

Creation of the territory

Identification of the Alto Rio Negro Indigenous Territory began with ordinance 1.892/E of 19 June 1985.[1] The Federation of Indigenous Organizations of the Upper Rio Negro (FOIRN) was created in 1987, with headquarters in São Gabriel da Cachoeira. Its goals are to obtain self-determination of peoples, defense and guarantee of indigenous lands, recovery of appreciation of indigenous culture, support for economic and social subsistence, and coordination with local and regional organizations.[7] The identification of the territory was submitted to the Ministry of Justice on 28 April 1993.[1]

Homologation of the Alto Rio Negro reserves was the main contribution to indigenous people by the Fernando Henrique Cardoso government of 1995–2003. Demarcation was undertaken between December 1995 and May 1996 coordinated by the Environment Ministry, with funding from a group of industrialized countries led by Germany. The work was coordinated by the FOIRN and the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA), and involved most of the 600 communities of the region.[8] The Alto Rio Negro Indigenous Territory was declared by decree 301 of 17 May 1996. It was homologated by decree of 15 April 1998.[1] Creation of an indigenous territory with 22 different ethnic groups was justified in part by their practice of linguistic exogamy.[7]

People

Ethnic groups

The majority of people in the Alto Rio Negro region are indigenous, despite forced migrations in the past to the Lower Rio Negro or to the cities of Manaus and Belém. The municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira has 37,896 people, of whom 29,017 are indigenous. It is one of the only municipalities in Brazil that has two official languages other than Portuguese, namely Tucano and Baniwa.[9] In January 2009 a Tariana mayor and Baniwa deputy mayor took office in São Gabriel.[10]

ISA estimated that there were 14,599 people in the Alto Rio Negro Territory as of 1996. According to Siasi/Sesai (Secretaria Especial de Saúde Indígena) this had risen to 21,291 by 2008 and to 26,046 by 2013. Indigenous people include Arapaso, Bará, Barasana, Desana, Carapanã, Kotiria, Cubeo, Macuna, Mirity-tapuya, Pira-tapuya, Siriano, Tucano and Tuyuka of the Tucanoan languages group, Baniwa, Baré, Koripako, Tariana, Warekena of the Arawakan languages group and Hupda and Yuhupde of the Nadahup languages group.[1] The Eastern Tucano live along the Uaupés River and its tributaries, and the Pira Paraná River in Colombia. The Arawak and Tariano live along the upper Rio Negro, Xié, Uaupés and Içana rivers and their tributaries. The Hupdah, Yuhup, Dâw, and Nadêb are semi-nomadic hunters and gatherers who live in the inaccessible inter-fluvial areas.[7]

Socioeconomic factors

According to the 2010 census by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics the territory had 15,183 indigenous inhabitants and just 102 non-indigenous people. Among the indigenous people, 48.1% were women and 51.9% men. Most of the inhabitants of the territory are literate. Of the 11,140 people over ten years old in 2010, 8,366 were literate and 2,774 illiterate. There were 9,242 people over the age of ten considered to be without income, with most others earning less than half the minimum wage.[10]

The residents have limited access to health services and economic alternatives.[7] Some efforts have been made to introduce new sources of sustainable income. Thus in April 2015 the Indigenous Organization of the Içana Basin (Oibi) inaugurated two Baniwa Pepper Houses, places for production, packaging and storage of the traditional Jiquitaia pepper, a "flour" of peppers with salt that carries a great range of varieties from the Baniwa women's gardens.[11]

In October 2016 ISA reported a growing problem with malaria in the territory. Indigenous people who travelled to urban areas to collect social benefit such as Bolsa Família were becoming infected and carrying the disease back to their communities. The health services in these communities were not able to quickly diagnose and treat the disease, causing rapid spread in areas that had formerly been unaffected.[12]

Organizations

74 indigenous organizations have been registered in the region.[1] There are Brazilian customs posts at Iauaretê, Querari, São Joaquim, Pari-Cachoeira and Tunuí. FUNAI has posts at Foz do Rio Içana, Foz do Rio Uaupés, Foz do Rio Xié, Melo Franco and Tunuê Cachoeira. There are two Catholic (Salesian) missions at Santa Izabel do Rio Negro and Içana, and an evangelical mission of the New Tribes Mission. The region, located where Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela meet, is of considered to be of strategic importance by Brazil, which has six army platoons located at key points.[13]

Environment

The Alto Rio Negro Indigenous Territory is in the Amazon biome.[1] The territory has blackwater rivers with low levels of fish, sandy and relatively infertile soil.[7] The lack of nutrients in the waters of the Rio Negro and its tributaries means that the fish obtain most of their diet from organic matter from the margin of the river, including insects, fruits, flowers and seeds. Although there are some large species, there are many smaller species, each with low numbers of individuals.[14]

The forest vegetation is 26.94% campinarana, 71.4% campinarana-rainforest contact, 0.78% open rainforest and 0.89% closed rainforest.[1] As of 2000 80,064 hectares (197,840 acres) had been deforested. This had risen to 93,830 hectares (231,900 acres) by 2014, with little deforestation towards the end of this period.[1]

In the late 1990s the National Department of Mineral Production (DNPM) reported 451 formal mining concessions in the territory covering 38% of the area.[15] The main threat comes from informal garimpeiro mineral prospectors.[1]

Notes

- Terra Indígena Alto Rio Negro – ISA.

- Estudo de caso ... Por La Tierra, p. 2.

- Plano de Etnodesenvolvimento do Território ..., p. 20.

- Plano de Etnodesenvolvimento do Território ..., p. 21.

- Plano de Etnodesenvolvimento do Território ..., p. 22.

- Plano de Etnodesenvolvimento do Território ..., p. 23.

- O Alto Rio Negro – Licenciatura Indígena.

- Estudo de caso ... Por La Tierra, p. 3.

- Estudo de caso ... Por La Tierra, p. 4.

- Estudo de caso ... Por La Tierra, p. 5.

- Estudo de caso ... Por La Tierra, p. 21.

- Zanchetta 2016.

- Estudo de caso ... Por La Tierra, p. 2–3.

- Estudo de caso ... Por La Tierra, p. 24.

- Plano de Etnodesenvolvimento do Território ..., p. 74.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alto Rio Negro. |

Sources

- Estudo de caso: Demarcação das Terras indígenas no Alto Rio Negro (PDF) (in Portuguese), Movimiento Regional Brasil Por La Tierra, 2016, retrieved 2017-03-05

- "O Alto Rio Negro", Licenciatura Indígena (in Portuguese), UFAM - Universidade Federal do Amazonas, retrieved 2017-03-04

- Plano de Etnodesenvolvimento do Território Rio Negro da Cidadania Indígena (PDF) (in Portuguese), Rio Negro: Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário Secretaria de Desenvolvimento Territorial, 2009, retrieved 2017-03-05

- "Terra Indígena Alto Rio Negro", Terras Indígenas no Brasil (in Portuguese), ISA: Instituto Socioambiental, retrieved 2017-03-04

- Zanchetta, Inês (25 October 2016), Malária avança na Terra Indígena Alto Rio Negro, Amazônia, retrieved 2017-03-04