Allergic inflammation

Allergic inflammation is an important pathophysiological feature of several disabilities or medical conditions including allergic asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and several ocular allergic diseases. Allergic reactions may generally be divided into two components; the early phase reaction, and the late phase reaction. While the contribution to the development of symptoms from each of the phases varies greatly between diseases, both are usually present and provide us a framework for understanding allergic disease.[1][2][3][4]

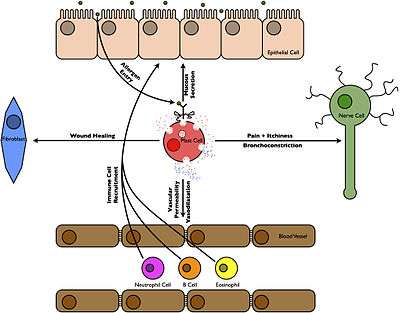

The early phase of the allergic reaction typically occurs within minutes, or even seconds, following allergen exposure and is also commonly referred to as the immediate allergic reaction or as a Type I allergic reaction.[5] The reaction is caused by the release of histamine and mast cell granule proteins by a process called degranulation, as well as the production of leukotrienes, prostaglandins and cytokines, by mast cells following the cross-linking of allergen specific IgE molecules bound to mast cell FcεRI receptors.[3] These mediators affect nerve cells causing itching,[6] smooth muscle cells causing contraction (leading to the airway narrowing seen in allergic asthma),[4] goblet cells causing mucus production,[1] and endothelial cells causing vasodilatation and edema.[6]

The late phase of a Type 1 reaction (which develops 8–12 hours and is mediated by mast cells)[5] should not be confused with delayed hypersensitivity Type IV allergic reaction (which takes 48–72 hours to develop and is mediated by T cells).[7] The products of the early phase reaction include chemokines and molecules that act on endothelial cells and cause them to express Intercellular adhesion molecule (such as vascular cell adhesion molecule and selectins), which together result in the recruitment and activation of leukocytes from the blood into the site of the allergic reaction.[3] Typically, the infiltrating cells observed in allergic reactions contain a high proportion of lymphocytes, and especially, of eosinophils. The recruited eosinophils will degranulate releasing a number of cytotoxic molecules (including Major Basic Protein and eosinophil peroxidase) as well as produce a number of cytokines such as IL-5.[8] The recruited T-cells are typically of the Th2 variety and the cytokines they produce lead to further recruitment of mast cells and eosinophils, and in plasma cell isotype switching to IgE which will bind to the mast cell FcεRI receptors and prime the individual for further allergic responses.

See also

References

- Fireman P (2003). "Understanding asthma pathophysiology". Allergy Asthma Proc. 24 (2): 79–83. PMID 12776439.

- Leung DY (1998). "Molecular basis of allergic diseases". Mol. Genet. Metab. 63 (3): 157–67. doi:10.1006/mgme.1998.2682. PMID 9608537.

- Hansen I, Klimek L, Mösges R, Hörmann K (2004). "Mediators of inflammation in the early and the late phase of allergic rhinitis". Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 4 (3): 159–63. doi:10.1097/00130832-200406000-00004. PMID 15126935.

- Katelaris CH (2003). "Ocular allergy: implications for the clinical immunologist". Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 90 (6 Suppl 3): 23–7. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61656-0. PMID 12839109.

- Janeway, Charles (2001). Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease (5th ed.). New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8153-3642-X.

- Trocme SD, Sra KK (2002). "Spectrum of ocular allergy". Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2 (5): 423–7. doi:10.1097/00130832-200210000-00010. PMID 12582327.

- Hinshaw WD, Neyman GP, Olmstead SM. "Hypersensitivity Reactions, Delayed". EMedicine.

- Rothenberg ME; Rothenberg, Marc E. (1998). "Eosinophilia". N. Engl. J. Med. 338 (22): 1592–600. doi:10.1056/NEJM199805283382206. PMID 9603798.