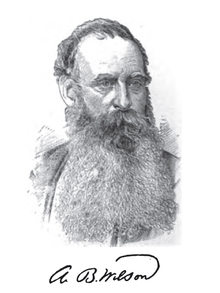

Allen B. Wilson

Allen Benjamin Wilson (1823–1888) was an American inventor famous for designing, building and patenting some of the first successful sewing machines.[1] He invented both the vibrating and the rotating shuttle designs which, in turns, dominated all home lockstitch sewing machines. With various partners in the 19th century he manufactured reliable sewing machines using the latter shuttle type.

Life

He was born at Willet, Cortland County, New York, October 18, 1823, the son of a wheelwright. At the age of eleven he was indentured to a farmer, remaining only a year. But he continued to work on a farm until he was sixteen, meanwhile learning the blacksmith's trade. He was next apprenticed to a cabinet-maker at Cincinnatus in the same county, but soon left the place, returning to his regular trade, as a journeyman, and found his way to Adrian, Michigan. While there, and early in 1847, he conceived the idea of a sewing-machine, never having heard of one, though in this country Elias Howe had already patented an invention, as had Bartholomy Thimonnierin France. Owing to an illness of several months duration. Wilson was not able to develop his ideas, although he had the various devices and adjustments clearly defined in his mind.[1]

In August, 1848, he moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he had obtained work, and soon began to put his ideas on paper in the form of full-size drawings. The firm with which he was connected dissolved in February, 1849, but Wilson remained with Amos Barnes, who continued the business, with the privilege of working evenings in the shop. On February 3, he began the construction of his first machine, and about April 1 completed it, making with it dress waists and other articles requiring fine sewing. His machine differed from those invented by Elias Howe, in the fact that, having a double-pointed shuttle, combined with the needle, it made two stitches instead of one with each complete movement; that is, one stitch on the forward movement and one on the return.[1]

In 1849 he moved to North Adams, Massachusetts, and induced Joseph N. Chapin, of that place, to purchase one-half of the invention for $300. With this money Wilson secured US patent number 7776, Nov. 12. 1850, which covered his new idea for a "vibrating shuttle" as well as a two-motion feed bar. His patent was the fifteenth recorded for an improved sewing machine. While his application was pending. parties owning an interest in a machine patented in 1848 by John A. Bredshaw. of Lowell, Massachusetts, claimed that the latter's patent covered a double-pointed shuttle, and threatened to oppose Allen B. Wilson. A compromise was made by which Wilson conveyed to Kline & Lee of New York city, onehalf of the patent. He also agreed to go into the manufacture and sale of the mechanics with those parties, but on November 25 sold them his interest in the patent, except the right for New Jersey, and that to sew leather in Massachusetts, for $2,000.[1]

Before the end of the year, Nathaniel Wheeler, of the firm of Warren, Wheeler & Woodruff, of Watertown, Connecticut, saw one of the machines in New York city, contracted with E. Lee & Co. to make 500, and induced Wilson to remove to Watertown to superintend the work.[2] Wilson soon became a partner in the firm, which had obtained the sole right to manufacture his machines, and on Aug. 12, 1851, patented a new machine, in which a rotating shuttle was used instead of a vibrating or oscillating shuttle. (This patent was for the complete machine; Wilson had patented the rotating shuttle itself two years earlier, in 1849.) Later, to avoid litigation, he contrived a stationary bobbin, which became the permanent feature of the Wheeler & Wilson sewingmachine.[1]

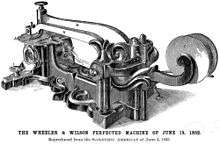

On the same day, August 12, Isaac M. Singer received his first patent on a transverse shuttle machine that became a formidable competitor. A new partnership was now formed, under the name of Wheeler, Wilson & Co., and in 1853 the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Co. was organized. On Dec. 19, 1854, Mr. Wilson received US patent 12116 for his "four-motion feed", which the machines of other inventors were forced to adopt. The advantage of his improvements was that the stitching made the strongest possible seam, being exactly even on both sides, with no threads showing above the surface that would be liable to wear oft and cause ripping. The first completed machine—that finished in 1851—sold for $125.[1]

In 1856 the firm removed to Bridgeport, Connecticut. Allen Benjamin Wilson retired from active participation in the business in 1853, but received a regular salary and considerable sums of money on the renewal of his intents. In 1863 he became a resident of Waterbury, Connecticut, where he engaged in other enterprises.[1]

His four-motion feed was judged so essential for sewing machines by the Congressional Committee on Patents that in 1874 a requested extension of his patents was denied.[3]

Allen Benjamin Wilson died at Woodmont, Connecticut, on April 29, 1888[1] and was interred at Riverside Cemetery in Waterbury, Connecticut.[4]

Wilson sewing machines

Allen B. Wilson's achievement was in the area of inventing and perfecting sewing machines. Two of those were considered the most ingenious and beautiful pieces of mechanism: the rotary hook and the four-motion feed. He claims to have conceived the idea of a sewing machine in 1847. His first machine was built during the spring of 1849, while he was in the employ of a Mr. Barnes, of Pittsfield, Mass., a cabinet maker. In the same year he built a second and better machine, and "up to this time," says, "I had never seen or heard of a sewing machine other than my own." He sold a one-half interest in the invention to Joseph N. Chapin, of North Adams, and with the proceeds took out his first patent, which bore the date November 12, 1850. It formed a lock stitch by means of a curved needle on a vibrating arm above the cloth plate, and a reciprocating two-pointed vibrating shuttle. The feed motion was obtained by the two metal bars which are seen intersecting above the shuttle race. The lower bar, called the feed bar, had teeth on its upper face, and by means of a transverse sliding motion it moved the cloth, which was placed between the two bars, the desired distance, as each stitch was made.[2]

In 1851 Wilson patented his famous rotary hook, which performed the functions of a shuttle by seizing the upper thread and throwing its loop over a circular bobbin containing the under thread. 'This simplified the construction of the machine by getting rid of the reciprocation motion of the ordinary shuttle, and contributed to make a light tool silent running machine, eminently adapted to domestic use.[2]

In 1854, Wilson patented his four-motion feed, in combination with a spring presser foot. The feed bar, as its name indicates, had four distinct motions, two vertical and two horizontal. It was first raised by the action of an eccentric on the driving shaft, then carried forward by a cam formed on the side of the eccentric (by which operation the work was shifted the desired distance), then it dropped, and finally it was drawn back by a spring to its original position. This machine used the curved needle and embodies the rotary hook and the four-motion feed. The latest type of this machine used a vertical needle bar and a straight needle.[2]

Wilson had the good fortune soon after securing his patent to interest Nathaniel Wheeler, a young carriage maker who possessed some capital, in his machine, and out of this connection grew the great house of Wheeler & Wilson.[2]

References

![]()

![]()

- "WILSON, Allen Benjamin". The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. IX. New York: James T. White & Company. 1899. p. 460. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- "The Sewing Machine". Scientific American. July 25, 1896. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- "Stitches in Time: 100 Years of Machines and Sewing". Museum of American Heritage. Palo Alto, California. October 4, 2004. Archived from the original on 2010-11-27. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- "Allen Benjamin Wilson". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

External links