Alexandre Deschapelles

Alexandre Deschapelles (March 7, 1780 in Ville-d'Avray near Versailles – October 27, 1847 in Paris) was a French chess player who, between the death of François-André Danican Philidor and the rise of Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais, was probably the strongest player in the world. He was considered the unofficial world champion from about 1800—1820.

| Alexandre Deschapelles | |

|---|---|

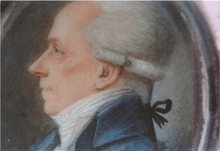

The only known likeness of Deschapelles. | |

| Full name | Alexandre Louis Honore Lebreton Deschapelles |

| Country | |

| Born | March 7, 1780 Ville-d'Avray, France |

| Died | October 27, 1847 (aged 67) Paris, France |

| World Champion | c. 1800 – c. 1820 (Unofficial) |

Family background

His parents were Louis Gatien Le Breton Comte des Chapelles, born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1741, and Marie Françoise Geneviève d'Hémeric des Cartouzières from Béziers in the south of France. Louis Gatien served as an officer in a dragoon regiment and later, through the influence of his close friend, the future admiral Louis-René Levassor de Latouche Tréville, became an officer in the royal household (Maison du Roi) with a number of rooms near the king's chambers in the château of Versailles.

Military career

Deschapelles was sent to the renowned military academy at Brienne with a view to a military career. When the influence of Louis Gatien's patron Latouche-Tréville ceased in 1791 and with the Reign of Terror looming, Louis Gatien decided to emigrate to Germany with his wife and two sisters of Alexandre. Soon after his father's emigration, Alexandre had to leave Brienne to join the French Republican army.[1] A soldier in Napoleon's army, Deschapelles lost his right hand in battle and was thereafter nicknamed "Manchot" (one-armed). He also received a massive sabre wound down the entire length of his face, which caused the Phrenology enthusiasts of his era to suggest "cranial sabre-wounds" were responsible for his amazing chess skill.[2]

Career as a player of chess and other games

Deschapelles had an incredible aptitude for games. Three months after learning the moves of Polish Draughts, he defeated the French champion of that game, and he claimed to have learned all of his chess knowledge in just four days.[3]

He was the teacher of Jacques François Mouret[4] and later, c. 1820, he accepted Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais as a student. After defeating John Cochrane and William Lewis two years later, Deschapelles switched to playing Whist (the Deschapelles coup in Contract bridge is named after him). Returning to chess competition in the mid-1830s, Deschapelles continued his trademark of always giving his opponents "odds".

Deschapelles reportedly once asked an opponent if they would play a game for stakes, to which they stated "My religion forbids me to play for money." Deschapelles replied "Mine forbids me to be absurd!"[5]

Notable chess matches

- 1821 John Cochrane, 6-1, with Cochrane having odds of a pawn and two moves

- 1821 William Lewis, 1-2, with Lewis having odds of a pawn and a move

- 1836 Pierre de Saint-Amant, 1½-1½

- 1842 Pierre de Saint-Amant, 3-2[6]

Coat of arms

Given to his grandfather Louis Cézaire Le Breton des Chapelles in 1760 by the French juge d'armes: "A silver shield with three green palms posed two and one. The shield is stamped with the profile of a helmet adorned with silver and green mantling."[7]

Sources

- Baudrier (Pierre).- Insurgés et forces de l'ordre en 1832. Alexandre Deschapelles..., Bulletin de l'Association d'Histoire et d'Archéologie du XXe arrqondissesment de Paris, N° 50, 4ème trimestre 2011, pp. 7–27.

References

- Czoelner, Robert (2011). Alexandre Honoré Deschapelles. US: Create Space. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-4609-6333-3.

- Fidelity History of Chess. 1988. p. 15.

- Walker, George (1850). Chess and Chess-Players: Deschapelles "The Chess-King". London: Charles J. Skeet. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992). The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 256. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- The Chess Player's Chronicle Vol. IX. 1849. p. 90.

- "The chess games of Alexandre Louis Honore Lebreton Deschapelles". www.chessgames.com. Retrieved 2016-05-04.

- Robert Czoelner, op. cit., p. 33. "Un écu d'argent à trois palmes de sinople posées, deux et un. Cet écu timbré d'un casque de profil orné de ses lambrequins d'argent et de sinople."

External links

- Alexandre Deschapelles player profile and games at Chessgames.com