Alexander Wienerberger

Alexander Wienerberger (December 8, 1891, Vienna — January 5, 1955, Salzburg) was an Austrian chemical engineer who worked for 19 years at chemical enterprises of the USSR. While he worked in Kharkiv, he created a series of photographs of the Holodomor of 1932-1933, which are photographic evidence of the mass starvation of the Ukrainian people at that time.

Alexander Wienerberger | |

|---|---|

| Born | December 8, 1891 |

| Died | January 5, 1955 (aged 63) |

Life

Alexander Wienerberger was born in 1891 (other sources mistakenly indicate 1898) in Vienna, in a family of mixed origin. Despite the fact that his father was Jewish and mother was Czech, Alexander himself, according to his daughter, considered himself an Austrian and an atheist.[1]

From 1910 to 1914 he studied at the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Vienna.

During the First World War he was mobilized into the Austro-Hungarian Army, participated in battles against the Russian army and was captured in 1915.

In 1917 he was allowed to move to Moscow, where he founded a chemical laboratory with friends. In the fall of 1919, he attempted to escape from Soviet Russia to Austria through Estonia using fake documents, but failed: in Pskov he was arrested by Cheka. Wienerberger was convicted of espionage. He spent a significant part of the 1920s in the Lubyanka prison in Moscow.[2] During his stay in prison, his skills as a chemist were appreciated by the Soviet government, which employed foreign prisoners worked in production. Wienerberger was appointed an engineer for the production of varnishes and paints, and later he worked in factories for the production of explosives.[3]

In 1927, his marriage with Josefine Rönimois, a native of the Baltic Germans, broke up. The ex-wife, together with daughter Annemarie and son Alexander, remained in Estonia (later Annemarie moved to Austria).

In 1928, for the first time after imprisonment, Wienerberger visited his relatives in Vienna and made a new marriage with Lilly Zimmermann, the daughter of a manufacturer from Schwechat. On his return to Moscow, restrictions were lifted from him, which allowed his wife to move to the Soviet Union. In 1931, his wife was allowed to briefly return to Vienna, where she gave birth to their daughter Margot.

In early 1930s, Wienerberger family lived in Moscow, where Alexander had a position at a chemical factory. In 1932 he was sent to Lyubuchany (Moscow Oblast) to the position of a technical director of a plastic factory, and in 1933 transferred to an equal position in Kharkiv.

Photographic evidence of the famine in 1932—1933

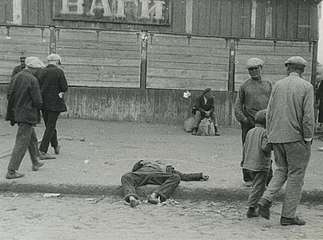

Living in Kharkiv, the then capital of the Ukrainian SSR, Wienerberger witnessed a massive famine and photographed the scenes he saw on the streets of the city, despite the threat of arrest by the NKVD.[2]

During his stay in Kharkov, Alexander Wienerberger secretly created about 100 photographs of the city during the Holodomor. His photographs depict queues of hungry people at grocery stores, starving children, bodies of people who died of starvation in the streets of Kharkov, and mass graves of victims of starvation. The engineer created his photographs using the German Leica camera, which was probably transferred to him by friends from abroad.[1]

Leaving for Austria in 1934, Wienerberger sent negatives through diplomatic mail with the aid of the Austrian embassy. Austrian diplomats insisted on such a measure of caution, since there was a high probability of a search of personal belongings at the border, and eventual discovery of photographs could threaten his life. Upon his return to Vienna, Wienerberger handed over the pictures to Cardinal Theodor Innitzer, who, together with the Secretary General of the International Committee of National Minorities Ewald Ammende, presented them to the League of Nations.[1]

In 1934, the Patriotic Front in Austria released Wienerberger's photos in a small brochure entitled “Rußland, wie es wirklich ist” (Russia, as it really is), but without attribution.[4]

Wienerberger's photographs were first made available to the public in 1935 thanks to the publication in the book "Should Russia starve?" (Muss Russland Hungern) by Ewald Ammende; the photos were not credited because of concerns for the safety of their creator.[5] In 1939, Alexander Wienerberger published in Austria his own book of memoirs about life in the Soviet Union, in which two chapters are devoted to the Holodomor.[6] Photos were also included in his memoirs published in 1942.[7]

In 1944, Wienerberger served as liaison officer of the Russian Liberation Army. After the war, he managed to avoid the transfer to Soviet troops - he ended up in the American zone of occupation in Salzburg, where he died in 1955.[8]

Currently, Wienerberger's photos have been republished in many other works, and are exhibited, in particular, in the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg.

References

- ""Це був геноцид": історія британської фотохудожниці, яка ширить пам'ять про Голодомор". BBC Україна. 23 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ""Рискуя попасть в застенки НКВД, мой прадед фотографировал жертв Голодомора"". Факты. 14 February 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.(in Russian)

- "Александр Вінербергер у спогадах доньки". Меморіал жертв Голодомору. 7 February 2016. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- Rußland, wie es wirklich ist!, hrsg. v. der Vaterländischen Front, für den Inhalt verantwortlich: Dr. Ferdinand Krawiec, Wien 1934, 16 S.

- Dr. Ewald Ammende, Muß Rußland hungern? Menschen- und Völkerschicksale in der Sowjetunion, Wien 1935, XXIII, 355 Seiten. Mit 22 Abb

- Alexander Wienerberger, Hart auf hart. 15 Jahre Ingenieur in Sowjetrußland. Ein Tatsachenbericht, Salzburg 1939

- Alexander Wienerberger, Um eine Fuhre Salz im GPU-Keller. Erlebnisse eines deutschen Ingenieurs in Sowjetrussland, mit Zeichnungen von Günther Büsemeyer, Gütersloh [1942], 32 S.

- Josef Vogl. Alexander Wienerberger — Fotograf des Holodomor. In: Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes (Hrsg.), Feindbilder, Wien 2015 (= Jahrbuch 2015), S. 259—272

External links

In Ukrainian

- Голодомор - Знімки австрійського фотографа-аматора, зображення жертв, місць масових поховань на околицях Харкова та вимерле від голоду село. МЗС України

- Александр Вінербергер у спогадах доньки. Національний музей Голодомору-геноциду BBC Україна

- Це був геноцид: історія британської фотохудожниці, яка ширить пам'ять про Голодомор

- Зустріч з правнучкою інженера Вінербергера, автора унікальних фото Голодомору.Національний музей Голодомору-геноциду BBC Україна

- Український Голодомор очима австрійця. Радіо «Свобода»

- Люди помирали просто на узбіччях - жахіття Голодомору очима австрійського інженера Вінерберґера. Gazeta.ua

- Люди Правди, кремлівська пропаганда і корисні ідіоти. Дзеркало тижня

- Невідомі фото Голодомору інженера Вінербергера. Радіо «Свобода»

- «Годували свиней трупами»: опубліковано невідомі раніше фото Голодомору. Obozrevatel

- Голодомор: унікальні фото від австрійського інженера. Ukrinform

- Іноземці про Голодомор: унікальні фото від австрійського інженера. Glavcom.ua

In other languages

- Holodomor in Kharkiv region. Photo by Alexander Wienerberger

- Alexander Wienerberger: His Daughter’s Memories [retrieved 20.10.2013].

- Alexander Wienerberger British photographic history

- Ukraine's Holodomor Through An Austrian's Eyes

- Josef Vogl. Alexander Wienerberger — Fotograf des Holodomor. In: Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes (Hrsg.), Feindbilder, Wien 2015 (= Jahrbuch 2015), S. 259—272

- Уникальные фото Голодомора в Украине: их тайком снял Александр Винербергер

- «Рискуя попасть в застенки НКВД, мой прадед фотографировал жертв Голодомора»