Alexander Thomson

Alexander "Greek" Thomson (9 April 1817 – 22 March 1875) was an eminent Scottish architect and architectural theorist who was a pioneer in sustainable building. Although his work was published in the architectural press of his day, it was little appreciated outside Glasgow during his lifetime. It has only been since the 1950s and 1960s that his critical reputation has revived—not least of all in connection with his probable influence on Frank Lloyd Wright.[1]

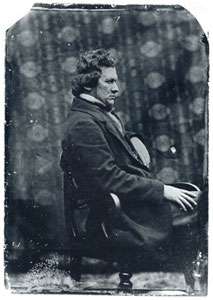

Alexander "Greek" Thomson | |

|---|---|

c. 1850 | |

| Born | 9 April 1817 |

| Died | 22 March 1875 (age 57) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Parent(s) | Elizabeth Cooper John Thomson |

| Buildings | Caledonia Road Free Church, Queen's Park United Presbyterian Church, St. Vincent Street Church, Holmwood House, Craigrownie Castle & others at Cove, Argyll |

Henry-Russell Hitchcock wrote of Thomson in 1966: "Glasgow in the last 150 years has had two of the greatest architects of the Western world. C. R. Mackintosh was not highly productive but his influence in central Europe was comparable to such American architects as Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. An even greater and happily more productive architect, though one whose influence can only occasionally be traced in America in Milwaukee and in New York City and not at all as far as I know in Europe, was Alexander Thomson".[2]

Early life

Thomson was born in the village of Balfron in Stirlingshire. The son of John Thomson, a bookkeeper, and Elizabeth Cooper Thomson, he was the ninth of twelve children. His father, who already had eight grown children from his previous marriage, died when Alexander was seven. The family consequently moved to the outskirts of Glasgow, but tragedy struck when the eldest daughter, Jane, and three of her brothers died between 1828 and 1830, the year that Alexander's mother died. The remaining children moved with one of the older brothers, William, a teacher, and his wife and child to Hangingshaw, just south of Glasgow. The Thomson boys all worked from a young age, but the children were also home schooled. It is believed that Alexander worked in a lawyer's office, possibly Wilson, James, and Kays, where his older brother, Ebenezer, was employed as a bookkeeper and where he later became a partner in the business.

Career

Alexander was eventually apprenticed to Glasgow architect Robert Foote, ultimately gaining a place in the office of John Baird[3] as a draughtsman. In 1848 Thomson set up his own practice, Baird & Thomson, with John Baird II, who became his brother-in-law, and this firm lasted nine years. In 1857, as "the rising architectural star of Glasgow,"[4] he entered into practice with his brother George where he was to enjoy the most productive years of his life. He served as president of both the Glasgow Architectural Society and the Glasgow Institute of Architects. Thomson was an elder of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and his deep religious convictions informed his work. There is a strong suggestion that he closely identified Solomon’s temple with the raised basilica of the same form of his three major churches.[5]

He produced a diverse range of structures including villas, a castle, urbane terraces, commercial warehouses, tenements, and three extraordinary churches. Of these, Caledonia Road Free Church (1856–57) is now a ruin, Queen's Park United Presbyterian Church (1869) was destroyed in WWII, and St Vincent Street Church (1859) is the only intact survivor. Hitchcock once stated, "[Thomson has built] three of the finest Romantic Classical churches in the world”.[6] Thomson developed his own highly idiosyncratic style from Greek, Egyptian and Levantine sources and freely adapted them to the needs of the modern city.

At the age of 34, Thomson designed his first and only castle, Craigrownie Castle, which stands at the tip of the Rosneath Peninsula in Cove, overlooking Loch Long. The six-storey structure is Scots Baronial in style, featuring a central tower with battlements, steep gables and oriel windows, in addition to a chapel and a mews cottage.

Thomson's villa designs were realized at Langside, Pollokshields, Helensburgh, Cove, the Clyde Estuary, and on the Isle of Bute. His "mature villas are Grecian in style while resembling no other Greek Revival houses,...[and they] are dominated by horizontal lines and rest on a strong podium."[7] According to Gavin Stamp, "Thomson carefully designed his villas with symmetries within an overall asymmetry in a personal language in which the horizontal discipline of a continuous governing order—whether expressed or implied—was never abandoned.[7] Regarding similarities to Frank Lloyd Wright, Stamp states, "It has often been remarked that there are clear resemblances between the early houses of the Prairie School and Thomson's horizontally massed design, with its low-pitched gables and spreading eaves -- together with a connecting garden." As Sir John Summerson noted, "There is something wildly 'American' about Thomson -- a 'New World' attitude. You can see it in the villas...a sort of primitivism, ultra-Tuscan."[7]

Later in his career he would abandon his eclecticism and adopt the purely Ionic Greek style for which he is best known, as such he is perhaps the last in a continuous tradition of British Greek Revival architects. In attacking the Gothic, he "insisted that 'Stonehenge is really more scientifically constructed than York Minster'...[alluding to] Pugin's comment that in their temples 'the Greeks erected their columns like the uprights of Stonehenge'."[8] Other important works still standing include Moray Place, Great Western Terrace, Egyptian Halls in Union Street, Grosvenor Building, Buck's Head Building in Argyle Street, Grecian Buildings in Sauchiehall Street, Walmer and Millbrae Crescents, and his villa, Holmwood House, at Cathcart.

Grave monuments designed by Thomson that are worthy of study include those to the Revd. A.O. Beattie and the Revd. G.M. Middleton, as well as that for John McIntyre in Cathcart Old Parish Cemetery.

Thomson was a visionary who introduced into our vocabulary some of the essential elements of sustainable housing. This argument hinges on an unrealized design Thomson prepared in 1868 for the Glasgow City Improvement Trust, an agency of the Town Council given the task of redeveloping a large area of slum housing centred on the medieval Old Town. The Trust invited Thomson and five other prominent architects to propose designs for the reconstruction of various parcels of land along the spine of Glasgow's High Street. Thomson suggested that closely spaced parallel tenements be built within the central courtyard, the ends of which will be open to facilitate ventilation. He also proposed that alternate streets be glazed for better warmth and safety for the residents. Although Thomson's ideas failed to catch on at the time, new research and CAD techniques have helped show how revolutionary was his proposal for improved workers' housing.

Writings

Thomson's published writings include the Haldane lectures on the history of architecture (1874) and the Inquiry as to the Appropriateness of the Gothic Style for the Proposed building for the University of Glasgow (1866) which attempted to refute Ruskin and Pugin’s claims for the superiority of Gothic.

Family

On 21 September 1847, Thomson married Jane Nicholson, granddaughter of the architect Peter Nicholson, in a double wedding ceremony with her sister, Jessie, who married John Baird II. They had twelve children in total and would later lose five of them in an epidemic.

One brother, George Thomson (1819–1878), became a baptist missionary in Limbe, Cameroon (then known as "Victoria"),[9] where he combined his religious activities with a passion for botany. An epiphytic orchid of the genus Pachystoma was named Pachystoma thomsonianum in his honour.[10]

His nephew,[9] Rev. William Cooper Thomson (1829-1878) was a missionary in Nigeria, after whose first wife the bleeding-heart vine Clerodendrum thomsoniae was named.[11][12]

Death

Thomson died on 22 March 1875 at his home in Moray Place in Strathbungo, Glasgow, fittingly in one of his own creations. The architect was buried in the lair adjacent to that in which his five deceased children were laid to rest, in Gorbals Southern Necropolis, on 26 March 1875, and he was joined there by his widow, Jane, in 1889.

His obituary appeared in "Building News" on 26 March 1875, written by his friend, Thomas Gildard, who also wrote his biography.[13]

Legacy

The Glasgow Institute of Architects set up The Alexander Thomson Memorial immediately following his death. A marble bust of the architect by John Mossman was presented to the Corporation Galleries, Sauchiehall Street, and is now displayed in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. The Alexander Thomson Travelling Studentship, of which the second winner was Charles Rennie Mackintosh, was established in his honor, "for the purpose of providing a travelling studentship for the furtherance of the study of ancient classic architecture, with special reference to the principles illustrated in Mr. Thomson’s works".[14]

Thomson was the pre-eminent architect of his era in Glasgow, yet until recently, his buildings and his reputation have been largely neglected in the city graced by his works.

Holmwood House is generally considered to be Thomson's finest and most original residential subject. Under the ownership of the National Trust for Scotland, Holmwood has been restored to its original condition and opened to the general public. During the renovation, nineteen panels of a classical frieze depicting scenes from Homer's Iliad were discovered under layers of paint and wallpaper, rendering Thomson's nickname all the more apt.

In 1999, a retrospective entitled Alexander Thomson: The Unknown Genius was held at The Lighthouse, reminding Glaswegians of the need to preserve the remaining examples of this unique architect's contribution to their city.

The British emigre architect George Ashdown Audsley closely followed Thomson's ornamentation for several of his secular buildings. The most notable surviving example is his Bowling Green Offices (completed 1896) in New York City. The highly carved granite base of this tall office building is in the Thomson manner with brick Chicago School style floors above.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alexander Thomson. |

- "Alexander Thomson: architectonics and ideals of the classic Glaswegian", John McKean, AA Files (Architectural Association, London), No 9, Summer 1985

- Dignity and Decadence, Richard Jenkyns, Harvard University Press, 1991.

- "Greek" Thomson, Ed. Gavin Stamp and Sam McKinstry, Edinburgh UP,1994

- 'Thomson's City: 19th Century Glasgow', John McKean, in "Places : A Forum of Environmental Design", University of California (Cambridge Mass), Volume 9, Number 1, Winter 1994, pp. 22–33. It is accessible at: "?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2011.

- Architecture of Glasgow, Andor Gomme and David Walker, Lund, 1987, 2nd. ed.

- Early Victorian Architecture in Britain Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Yale, 1954

- The Life and Work of Alexander Thomson, Ronald MacFadzean, London, 1979

- Alexander "Greek" Thomson, Gavin Stamp, 1999

- The Greek Revival, J Mourdant Crook, 1972.

- "Glasgow: from 'Universal' to 'Regionalist' City and beyond - from Thomson to Mackintosh", John McKean, in Sources of Regionalism in 19th Century Architecture, Art and Literature, ed. van Santvoort, Verschaffel and De Meyer, Leuven, 2008

See also

References

- Andrew MacMillan in "Greek" Thomson, Stamp et al., p.207

- Letter by Hitchcock published in the Glasgow Herald, 4 March 1966, on the occasion of the proposed demolition by the City council of the Caledonia Road Church

- "Dictionary of Scottish Architects - DSA Architect Biography Report (December 9, 2015, 11:41 am)". www.scottisharchitects.org.uk. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- Stamp, Gavin. "At Once Classic and Picturesque...": Alexander Thomson's Holmwood. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 57.1 (1998):46-58.

- J. Stevens Curl, "St Vincent Street Church as a mnemonic of the Temple of Solomon", p.6 ff, The Alexander Thomson Society Newsletter, No. 12 January 1995.

- H. R. Hitchcock, Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, 1963, p.63

- Stamp, Gavin. "At Once Classic and Picturesque...": Alexander Thomson's Holmwood. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 57.1 (1998): 46.

- Stamp, Gavin. "At Once Classic and Picturesque...": Alexander Thomson's Holmwood. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 57.1 (1998): 50.

- Ray Desmond & Christine Ellwood (1994). Dictionary of British and Irish Botanists and Horticulturists. CRC Press. p. 681. ISBN 0-85066-843-3.

- James Herbert Veitch (2006). Hortus Veitchii (reprint ed.). Caradoc Doy. p. 70. ISBN 0-9553515-0-2.

- Balfour, J.H. Description of a new species of Clerodendron... Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal n.s., 15(2): 233–235, t. 2. 1862.

- Umberto Quattrocchi (2000). CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names. CRC Press. p. 560. ISBN 0-8493-2675-3.

- Dictionary of Scottish Architects: Gildard

- "The Alexander Thomson Memorial". Greekthomson.com.

External links

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- The Alexander Thomson Society

- Alexander Greek Thomson - Architect

- Photo Guide to some of Thomson's best known buildings

- List of Thomson's buildings

- Webpage on Holmwood House

- St Vincent Street Free Church of Scotland, Glasgow

- Craig Ailey Villa, Cove, Firth of Clyde

- Canmore page featuring interior and exterior photographs of Caledonia Road Church