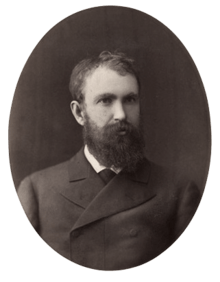

Alexander Ertel

Alexander Ivanovich Ertel (Russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Э́ртель) (July 19, 1855 – February 7, 1908), was a Russian novelist and short story writer.

Alexander Ertel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 19, 1855 Voronezh, Russian Empire |

| Died | February 7, 1908 (aged 52) Moscow, Russian Empire |

Biography

Ertel was born near Voronezh, where his father – a soldier in Napoleon’s army, captured by the Russians – had settled and become an estate agent. He never completed school, and was largely self-educated. He published his first collection of stories called Notes from the Steppes in 1883. He was imprisoned in 1884 for his revolutionary ties, and afterwards exiled to Tver for four years. He published a number of novellas and stories in the 1880s and 1890s, including A Greedy Peasant (1886), and the two epic novels The Gardenins (1889), and Change (1891). When The Gardenins was republished in 1908, it featured a preface by Leo Tolstoy, who admired Ertel’s work.[1][2]

After his death, his widow Marya Vasilievna lived in Moscow, taking in paying guests who had come to learn Russian; she was helped by their younger daughter, Elena (Lolya or Lola), who became a literary translator. Their elder daughter also became a literary translator, working in England as Natalie Duddington. Among Madame Ertel’s pupils was Bruce Lockhart; in his famous Memoirs of a British Agent (1932) he recorded that, thanks to her and Lolya, he became proficient in Russian, acquired a modicum of culture, and developed a deep affection for all things Russian. Marya died in the typhus epidemic in 1919; Lolya survived it and managed to escape to Britain in 1927.

English translations

His story The Specialist, and his novella A Greedy Peasant are available in English translation in Eight Great Russian Short Stories, A Premier Book, Fawcett Publications, 1962. The translator of these two works was his daughter Natalie Duddington, well known for her translations of other Russian authors.[3]

References

- Terras, Victor (1990). Handbook of Russian Literature. Yale University Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 0300048688. Retrieved 2012-04-13.

- Mirsky, D. S. (1999). A History of Russian Literature. Northwestern University Press. p. 352. ISBN 0810116790. Retrieved 2012-04-13.

- Dodson, Daniel (1962). Introduction to Eight Great Russian Short Stories. Fawcett Publications.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alexander Ertel. |