Albrecht Meyer

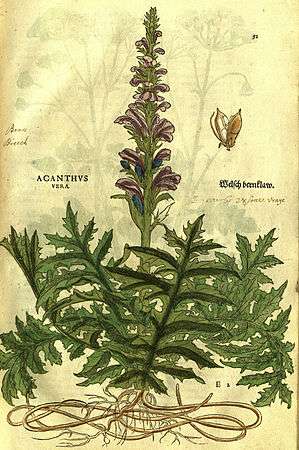

Albrecht Meyer also known as Albertus Meyer in Latinised form, was a botanical illustrator noted for his more than 500 plant images in Leonhart Fuchs's epic pre-Linnean publication of 1542, De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes, published in Latin and Greek, and almost immediately translated into German. At the time it was regarded as one of the most beautifully illustrated books on plants and a jewel in the crown of German Renaissance.

Collaborations

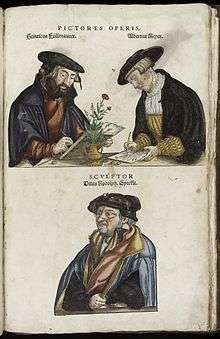

Meyer collaborated with the painter Heinricus Füllmaurer and the engraver Veit Rudolph Speckle (d.12 December 1550 Straßburg) in producing the woodcuts for the book, which, unusually for its time, named the contributing artists and included their portraits. Fuchs, whose herbal had been inspired by Brunfels's work "Herbarum vivae imagines" which had appeared twelve years earlier, praised the illustrations as having been carried out with 'great diligence and artifice', and went on to state that 'shading and other less crucial things with which painters sometimes strive for artistic glory' had been shunned in order to make the images truer to nature. The book appeared in both coloured and uncoloured versions. Fuchs planned for the illustrations to be coloured and did not want their appearance disfigured by excessive shading. Although some copies of the work were issued as coloured, many were worked on after publication. The text, like that of Brunfels', was taken from ancient authors.[1][2] "De Historia" continued a long tradition of herbals - books describing the medicinal uses of plants - but broke with tradition by using lifelike illustrations rather than the schematic and often fanciful representations.

The remarkably detailed woodcuts include the first published images of over 100 new plants from the Americas, such as pumpkin, marigold, maize, squash, chili peppers and tobacco – native to Mexico and brought to Europe from the New World. Leonhart Fuchs was a child prodigy, matriculating from Erfurt University by the age of twelve, and then obtaining a degree in medicine at Ingolstadt. He rendered outstanding medical service during the 1529 Sweating Sickness plague. The illustrations were drawn from nature by Albert Meyer, using mature plants which Fuchs often provided from his garden in Tübingen. The accuracy of the plates which show the flowers, roots and the plant habit, led to its being used as a reference work by European physicians and many famous herbaria of the sixteenth century, notably that of Dodoens. William Morris, the English artist and designer, possessed a copy of the book and some of his designs drew inspiration from the plates.[3]

The "Historia" was published in a German language folio edition a year after the original. The folio editions were bulky and difficult to use, and smaller, pocket editions soon appeared. During Fuchs' lifetime the book went through thirty-nine imprints in Latin, German, French, Spanish and Dutch. The woodblocks were used and copied for a further three hundred years. Fuchs laboured on a greatly expanded version of the work for the final twenty-four years of his life. The manuscript of this work, which was never published, is preserved in the Austrian National Library and is dubbed the 'Vienna Codex'.[4]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albrecht Meyer. |

Gallery of Plates from De Historia Stirpium

Poppy

Rose

Asparagus officinalis

References

- "Early Naturalists" (1912) - Louis Compton Miall

- "The Cambridge History of Science" vol3 - Katharine Park, Lorraine Daston

- Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- Glasgow University Library Archived 2013-04-25 at the Wayback Machine