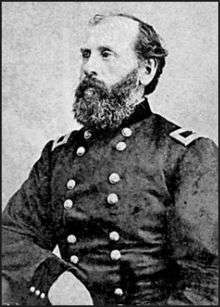

Albin Francisco Schoepf

Albin Francisco Schoepf (Polish: Albin Franciszek Schoepf; March 1, 1822 – May 10, 1886) was a European-born military officer who became a Union brigadier general during the American Civil War, best known as the commanding officer of Fort Delaware, a wartime camp for Confederate prisoners of war.

Albin Francisco Schoepf | |

|---|---|

Albin F. Schoepf | |

| Born | March 1, 1822 Podgórze, Poland |

| Died | May 10, 1886 (aged 64) Washington, D.C. |

| Place of burial | Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1841–1849 (Austria) 1849–1851 (Ottoman Empire) 1861–1866 (USA) |

| Rank | Major (Austria) Major (Ottoman Empire) |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Early life

Schoepf was born in Podgórze, Poland, which was then part of the Austrian kingdom of Galicia. He entered the Vienna Military Academy in 1837, became a lieutenant of artillery in 1841,[1] and served in Hungary as a captain in the Austrian Army. At the beginning of the Hungarian Revolution in 1848, he resigned his commission and enlisted as a private in the Hungarian Revolutionary Army under Lajos Kossuth. He was soon promoted to major.[2] When Kossuth abdicated in 1849, Schoepf was exiled to Turkey, where he served under Gen. Jozef Bem against the insurgents at Aleppo, and afterward became instructor of artillery in the Ottoman Empire's army with the rank of major.

Washington, D.C.

He emigrated to the United States in 1851. Befriended by Joseph Holt, Schoepf served as a clerk first in the U.S. Coastal Survey and later in the U.S. Patent Office and the War Department (working under Holt). While working in Washington, D.C. Schoepf married Julie Bates Kesley in 1855; they had 9 children together.

Civil War

Appointed a brigadier general of volunteers on September 30, 1861, Schoepf's brigade fought well at the Battle of Camp Wildcat, repulsing Confederates under Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer. This was followed a few weeks later by Schoepf's precipitate retreat, by order of his superior officer, from London, Kentucky, to Crab Orchard, which the Confederates called the “Wild-Cat stampede.” Schoepf and his troops later fought Zollicoffer at the Battle of Mill Springs.

Proving himself an aggressive and able field commander, Schoepf was promoted to division command in August 1862, but often found himself at odds with Army of the Ohio commander Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, especially after being denied orders to attack until late in the Battle of Perryville. Appointed to a military board of inquiry investigating Buell's conduct during the campaign, Schoepf made no secret of his disapproval of his commander's actions — so much so that Buell raised Schoepf's hostility as an issue. Not wanting his involvement to affect the Buell investigation's outcome, Schoepf asked Army general-in-chief Henry W. Halleck to transfer him to another assignment.

On April 13, 1863, Schoepf was ordered to report to Fort Delaware as commanding office and served the balance of the war in that command. He was mustered out of service on January 15, 1866. Fort Delaware, located on Pea Patch Island, served as a prisoner-of-war camp for captured Confederate soldiers and sailors. According to Laura M. Lee, historian at Fort Delaware State Park, "...it was not a pleasant place by any standards, historical records and the death rate testify to the fact that it was one of the more survivable prison camps, North or South."[3] The prisoner complex held up to 11,500 at its peak (July 1863), with a cumulative population of 33,000 by war's end. According to "They Died at Fort Delaware 1861–1865" by historian Jocelyn P. Jamison and compiled from NARA records, about 2,460 prisoners died, 109 guards and 39 civilians.[4]

Postbellum career

After the war, Schoepf returned to the U.S. Patent Office and died after a long illness, likely stomach cancer. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Notes

- While these dates seem correct by multiple sources, this is a very quick progression through the academy. Normally it took 8 years to move through the academy (see http://listsearches.rootsweb.com/th/read/AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN-MILITARY/2005-01/1104873140), on the other hand, he was late going to the academy (from the same source).

- Fetzer, D.; Mowday, B.E.; Jennings, L.C. (2005). Unlikely Allies: Fort Delaware's Prison Community in the Civil War. Stackpole Books. p. 79. ISBN 9780811732703. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- "Interpreter's Notes by Laura Lee, Fort Delaware". Archived from the original on 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- "FDS Website Home Page". fortdelaware.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

References

- Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. The Civil War Dictionary. New York: McKay, 1988. ISBN 0-8129-1726-X. First published 1959 by McKay.

- Fetzer, Dale, and Bruce E. Mowday. Unlikely Allies: Fort Delaware's Prison Community in the Civil War. Mechanicsville, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 2000. ISBN 0-8117-1823-9.

- Welsh, Jack D. Medical Histories of Union Generals. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-87338-649-4.

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- Jamison, Jocelyn P. "They Died at Fort Delaware 1861–1865". Delaware City, Delaware: Fort Delaware Society, 1996.

External links

- "Albin Francisco Schoepf". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- "Fort Delaware". FortWiki Historic U.S. and Canadian Forts. fortwiki.com. Retrieved 2014-10-10.