Alaska Syndicate

In an effort to thwart statehood and Alaskan home rule from Washington D.C., the "Alaska Syndicate," was formed in 1906 by J. P. Morgan and Simon Guggenheim. The Syndicate purchased the Kennicott-Bonanza copper mine and had majority control of the Alaskan steamship and rail transportation. The syndicate also was in charge of a large part of the salmon industry.

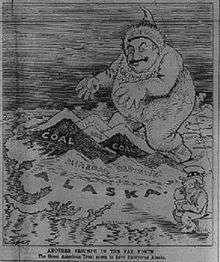

Guggenmorgan/Morganheims

The Alaska Syndicate faced intense scrutiny from Alaskans in favor of increased autonomy over their own affairs. The Syndicate, which divided its shares equally amongst M. Guggenheim & Sons and J.P. Morgan & Co.,[1] continued to buy up hundreds of thousands of acres of wilderness, which gave rise to the notion that Alaska was "First a Colony of Russia, then a colony of Guggenmorgan".[2] Forester and conservationist Gifford Pinchot led the charge against the Alaska Syndicate and the so-called "Morganheims" and their supporter in Washington, Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger. Ballinger, a perceived enemy of the conservation movement of which Pinchot was a leading mover, had intervened in and investigated the legality of coal mining claims made by Clarence Cunningham, a partner of J.P. Morgan and the Guggenheims. Cunningham had been the representative of 32 individuals seeking claims in what would soon be protected by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908 as the Chugach National Forest. Cunningham was accused of staking the claims on 5,280 acres in order to later transfer them to the Alaska Syndicate, despite this surrogacy being specifically banned by the recently passed Alaska Coal Act.[3]

Despite his initial validation of the Cunningham claims, and successfully weathering (with the help of Senator Simon Guggenheim) a Congressional investigation into his dealings, Ballinger resigned in 1911 under sustained pressure from Pinchot and Congressional Democrats. His successor Walter Fisher soon rejected the Cunningham claims.[4] The controversy also provided substantial fodder to further the aims of proponents of Alaskan home rule. Coupled with the growing distaste for wealthy bankers and "Captains of Industry" that was brewing across the country at the time, the public images of the Morgans and Guggenheims took a great hit. Often portrayed together in political cartoons (with thinly veiled anti-Semitism) as the Shylock-like monster Morganheim (or Guggenmorgan), the controllers of the Alaska Syndicate continued to be a lightning rod for the press, conservationists, anti-business forces, small merchants, and all others who believed that Alaska's pristine lands should be exploited only through the careful regulation of the government.[2]

Stephen Birch

In 1901 Stephen Birch, a young mining engineer, was in Valdez, Alaska in search of prosperous mining claims. That summer, he was approached by Clarence Warner and Jack Smith – two members of the McClellan group – for financial investment to develop the Bonanza claim.[5] Birch was enthusiastic about the opportunity and in the fall of 1902, financed by wealthy New York financiers H.O. Havenmeyer and James Ralph, he began to purchase pieces of the Bonanza claim from the members of the McClellan group.[5][6] After the acquisition of the original McClellan group claims, Birch realized he desperately needed funding to construct a railway from the port of Valdez to the Bonanza mine nearly 200 miles away. In 1905, Birch had gained support from John Rosene of Northwestern Commercial Company who agreed to construct the railway from Valdez to Bonanza mine; construction began in June 1905.[6] It soon became apparent to Birch more funding was necessary to complete the railway and to develop the copper mines. In his search for investors, Birch met with J.P. Morgan Jr., W.P. Hamilton and Charles Steele of J.P. Morgan & Co. in March 1906. Two months later in May, Birch met with Daniel Guggenheim, who was already convinced to back the railroad.[6] As a result of Birch's efforts, in June 1906 Guggenheim "joined with the house of Morgan to form the Alaska Syndicate with the specific goal of developing Birch's copper mine."[6] Birch was one of the three managing directors of the syndicate.[6] With the financial backing of Guggenheim and Morgan, the railway was built and Birch developed the Kennecott copper mines, which consisted of several large copper mines including the Bonanza and Jumbo mines. In 1915 the Kennecott Copper Company was established by the Alaska Syndicate of which Birch became president.[5]

Copper River and Northwestern Railway

After acquiring the copper ore deposits in 1906, it became necessary to develop transportation infrastructure, for "without transportation, the world's richest copper deposits were valueless."[7] While the unique difficulties of development in the north did not inspire the building of roads, the lure of profits attracted railway companies.[8]

Michael James Heney (1864-1910), a Canadian of Irish descent, had a clear passion for the railroad. He first left home, briefly, at the age of fourteen to work on the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). When Heney was 17, he left again to work on the CPR in Elkhorn, Manitoba. Upon its completion, Heney, at age 21, was ready to become an independent contractor. After building the Seattle Lake Short and Eastern Railroad, Heney had earned the epithet "the boy contractor." He garnered an international reputation following his work on the White Pass and Yukon Railway for Close Brothers and Company of London.[9]

The Alaska copper claims attracted Heney's attention to the Copper River valley. He surveyed a route that would well-serve the mining interests of the area and founded the Copper River Railway Company. Heney chose Cordova as port for his railroad and, supported by Close Brothers and engineer Erastus Corning Hawkins, began construction in April 1906.[9] At the same time, the Alaska Syndicate was attempting a railroad from Valdez through the Keystone Canyon. Having given up on the Valdez route, in 1906 the Alaska Syndicate bought Heney's surveyed route, through the Abercrombie Canyon, for $250,000 from his Copper River Railroad company. After contracting Heney and purchasing the remaining Copper River Railroad company assets, the venture was renamed the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad.[10]

The Alaska Syndicate then turned its attention to Katalla, another possible port with both oil and coal deposits. Katalla, however, was subject to violent storms, which destroyed the dock and much of the town.[11] In the end, it was Heney's 195 mile route from Cordova to Kennecott which was completed in 1911. Many workers in Katalla would hold out hope for a spur railroad, in order to utilize the coal reserves as fuel for the railroad, but eventually, the Gugenheims converted their engines from coal to oil powered, eliminating the need.[10]

The syndicate's railroad construction was not without competition and confrontations. Although various means were employed to discourage competing railways, violence was used on two occasions. The more famous occasion involved the fatal shooting of a worker from the Alaska Home Railroad, a rival who wanted to pursue the Valdez route that the syndicate had abandoned. The deputized leader of the band who shot the worker was subsequently tried and "the syndicate lost much face as charges of bribery and other irregularities were aired."[8]

The terrain presented difficulties including bridging the intense flow of the Copper River, building around glaciers, and chiseling into the rock faces of two canyons.[7] The railroad cost $20 million, including $1.5 million for the construction of the "Million Dollar Bridge," which crosses the Copper River between the Miles and Childs Glaciers.[10]

When the great depression hit, the Alaska Syndicate was not immune. The price of copper collapsed and mining activities came to an end in the summer of 1935. The Copper River and Northwestern railroad was last used in November 1938.[10]

The Birth of Kennecott

The Alaska Syndicate took form in 1906 when the financial interests of JP Morgan merged with the mining interests of the Guggenheims, with Stephen Birch as the managing director. Stephen Birch also expanded the Syndicate to other ventures. Eventually, it acquired an important mercantile business, Alaska's second largest company, its largest steamship and its longest railroads.[12]

The discovery of high-grade copper ore at Kennecott attracted attention in the mining industry. Steven Birch was one of the earliest people who purchased claims in the Kennecott ores when it was first discovered. He persuaded JP Morgan and the Guggenheims to invest in the deposit at Kennecott. The operation and the development of the ores in Kennecott falls in the successions of two organizations: The Alaska Syndicate and the Kennecott Copper Corporation. The two organizations share the same goals across different historical times. They are stability of supply, transportations and markets.[13]

The Alaska Syndicate, as typical businessmen in the 19th century, used bribes and promises to win business favors in the political system. However, their methods were seriously challenged by James Wickersham who led the Alaskan people against monopolism. The famous Ballinger-Pinchot Affair [14] eventually changed the political landscape across the board.[8] For example, it caused the resignation of Ballinger, who was a politician in favor of the Alaska Syndicate. Also, the effects of this anti-syndicate climate caused the failure of President Taft's re-election to the presidency. His successor, president Wilson had a series of political reforms which made the old methods of the Alaska Syndicate to not work in the new times. Consequently, the Alaska Syndicate invited public participation and a new corporation, the Kennecott Copper Corporation, was founded. Essentially the same people controlled the Corporation, but with different tactics and methods to manage the organization.

James Wickersham

James Wickersham was district judge and delegate of the House of Representatives for the Territory of Alaska 1909-1917, 1919, and 1921, 1931-1933.

The Territory of Alaska had a man who stood up for the area, and this man's name was James Wickersham. James Wickersham was a major opponent of the Alaska Syndicate.

"An affidavit similar to the one herewith enclosed was submitted by Hon. James Wickersham Delegate from Alaska, on May 24, 1910, together with a copy of a letter which he forwarded to the Attorney General on the same date, with reference to the matter of furnishing coal to military posts at Forts Davis and Liscum, Alaska, and on May 28, 1910, this office informed the Secretary of War that the papers referred to would be held, pending call from the Attorney General for any papers or information that may be on file in this office. As it is understood that the Department of Justice was investigating the matter, no further action was taken by his office.

"However, on November 26, 1910, Mr. Stuart McNamara, of No. 52 William Street, New York, formerly connected with the Department of Justice, requested, and was furnished, a brief statement of facts as shown by the records of this office, it being understood that fee intended to assist the Department of Justice in the investigation of the matter.

"No call has yet been received from the Attorney General for any papers or information that may be on file in this office."[14]

Efforts toward self-government were complicated by the influence in Washington of the "Alaska Syndicate," formed in 1906 by the fortunes of J. P. Morgan and Guggenheim. The Syndicate had purchased the large Kennicott-Bonanza copper mine and controlled much of Alaskan steamship and rail transportation, as well as a major part of the salmon canning industry. The Syndicate lobby in Washington had successfully opposed any further extension of Alaskan home rule. James Wickersham, who had been appointed to an Alaskan judgeship in 1900 by President McKinley, became alarmed by the potential influence of incorporated interests in the territory and took up the struggle for Alaskan self-government. Wickersham argued that Alaska's resources should be used for the good of the entire country rather than exploited by a select group of large, absentee-controlled interests—home rule, he claimed, would assure more just utilization of the territory's natural wealth. The 1910 Ballinger-Pinchot affair, which involved the illegal distribution of thirty-three federal government Alaskan coal land claims to the Guggenheim interests, culminated in a Congressional investigation and brought Alaska directly into the national headlines.[15]

In the midst of it all, James Wickersham was a big contribution to Alaska becoming a state.

Kennicott and Kennecott

The town of Kennicott was home to over 500 miners and their families, which is now a small community. It was a classic "dry" company town. Most of the miners lived in company housing and life revolved around the mining operation. The Kennecott Copper Mine was the largest copper mine in the world at some time. (?) The mine operated from 1911 to 1938 in the town that is known now as McCarthy in Wrangell St. Elias National Park. In the spring of 1915, Guggenheim and Morgan formed the Kennecott Copper Corporation. The total production was valued at over $200 million which is now comparable about $3 billion. After all of the rich copper deposits were depleted the mines of Kennecott along with the railroad, ceased operations.[16] The Alaska Syndicate was formed to develop the mine which eventually expanded into coal, salmon, and infrastructure throughout the state. Their influence helped to prevent Alaska from becoming a state as early as 1916. While the Kennecott Mining Company was still in operation they had developed other properties that still exist today. The different spelling between Kennicott and Kennecott was a simple mistake of one letter that the mine owner accidentally spelled wrong and never changed.[17]

The Kennicott glacier was named after Robert Kennicott. Robert Kennicott was a part of the Western Union Telegraph Expedition and arrived in San Francisco in April 1865. The group moved north to Vancouver where Kennicott suffered a period of ill health. After his recovery they moved north again to Alaska in August 1865. Kennicott died in May 1866, likely of congestive heart failure, while traveling up the Yukon River.

Today the tourism makes up the majority of the local economy. People from all over the world come and visit the remains of the Kennecott mines. Even though Kennicott is not a copper mining town anymore it is still a company town of sorts with it having headquarters to the National Park Service. McCarthy is still able to be accessed by the McCarthy Road which follows the rail bed of the old Copper River and Northwestern Railway from Chitina to McCarthy.[16]

References

- Carosso, Vincent (1987). The Morgans: Private International Bankers 1854-1913. Harvard University Press. p. 463.

- Davis, John (1989). The Guggenheims: An American Epic. New York: SPI Books. p. 107.

- Claus, Naske (2011). Alaska: A History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 149–151.

- Naske, Claus (2011). Alaska: A History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 151.

- Tower, Elizabeth (1996). Icebound Empire: Industry & Politics on the Last Frontier. Anchorage, AK: Elizabeth A. Tower. pp. 71, 72, 112, 223–225. ISBN 9781888125054.

- Tower, Elizabeth (1990). Ghosts of Kennecott: The Story of Stephen Birch. Anchorage, AK: Elizabeth A. Tower. pp. 17, 21, 29–30, 32–33, 34, 35. ISBN 9781594330070.

- Grauman, Melody Webb (1978). "Kennecott: Alaskan Origins of a Copper Empire, 1900-1938". The Western Historical Quarterly.

- Naske, Claus M. (2011). Alaska: A History. Norman, OK.: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 148, 150.

- Minter, Roy (2003). "HENEY, MICHAEL JAMES". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- Nourse, Mike (2006). "The Great Alaska Copper Rush!". Alaska Coin Exchange. Archived from the original on 2012-09-03. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- "Alaska History & Cultural Studies". Southcentral Alaska. 1900-1915 Fight for a Railroad. 2006. Archived from the original on 2015-03-28. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- Stearns, "Morgan-Guggenheim Syndicate" (M.A. thesis, Columbia University, 1936).

- Grauman (1978). "Kennecott: Alaskan Origins of a Copper Empire, 1900-1938". Western Historical Quarterly.

- United States Congressional serial set, issue 6117 pg. 75-79

- Gislason, Eric. A Brief History in Alaska Statehood

- "McCarthy, Kennecott, & the Kennicott Valley". McCarthy, Kennecott, & the Kennicott Valley. Largest National Park. 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- "Trek Alaska". Trek Alaska Wilderness Adventure. Retrieved December 10, 2014.