Barid

The barīd (Arabic: بريد, often translated as "the postal service") was the state-run courier service of the Umayyad and later Abbasid Caliphates. A major institution in the early Islamic states, the barid was not only responsible for the overland delivery of official correspondence throughout the empire, but it additionally functioned as a domestic intelligence agency, which informed the caliphs on events in the provinces and the activities of government officials.

Etymology

The etymology of the Arabic word barid has been described by historian Richard N. Frye as "unclear".[1] A Babylonian origin has been suggested by late-19th-century scholars who offered the following disputed explanation: berīd = Babyl. buridu (for the older *(p)burādu) = 'courier' and 'fast horse'.[2] It has also been proposed that, since the barid institution appears to have been adopted from the courier systems previously maintained by both the Byzantines and Persian Sassanids, the word barid could be derived from the Late Latin veredus ("post horse")[3][4][5] or the Persian buridah dum ("having a docked tail," in reference to the postal mounts).[6]

History

The Muslim barid was apparently based upon the courier organizations of their predecessors, the Byzantines and Sassanids.[7] Postal systems had been present in the Middle East throughout Antiquity, with several pre-Islamic states having operated their own services. A local tradition of obliging the population living next to roads to carry the luggage of passing soldiers and officials, or of having the entire population contribute pack animals to the state as in Ptolemaic Egypt, has been documented since at least the time of the Achaemenid Empire and had been enforced by Roman legislation in the 4th century.[8][9]

The barid operated from Umayyad times, with credit for its development being given to the first Umayyad caliph Mu'awiyah ibn Abi Sufyan (r. 661–680). Mu'awiyah's successor Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685–705) strengthened the organization, making additional improvements to it after the end of the Second Fitna.[10][3][11] The Umayyads created a diwan or government department to manage the system[12] and a separate budget was allocated for its costs.[13]

Following the Abbasid Revolution in 750, the barid was further strengthened by the new dynasty and became one of the most important institutions in the government.[3] The second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775) placed particular importance on the service and utilized it as an intelligence tool with which he could monitor affairs throughout the empire.[14] Under his successors, oversight of the barid was often entrusted to a prominent official or close associate of the caliph, such as the Barmakid Ja'far ibn Yahya or Itakh al-Turki.[3][15]

After the political fragmentation of the Abbasid Caliphate in the ninth and tenth centuries, the central diwan al-barid was overseen by the Buyids (945–1055),[16] but the organization seems to have declined during this period.[3] The service was eventually abolished by the Seljuq sultan Alp Arslan (r. 1063–1072), who considered its capacity for intelligence-gathering to have been diminished.[17] Some other Muslim states, such as the Samanids of Transoxiana, maintained their own barid systems at various times,[18] and in the thirteenth century a new barid was created in Egypt and the Levant by the Mamluk sultan Baybars (r. 1260–1277).[19]

Functions

Correspondence and travel

The barid provided the caliphs with the ability to communicate with their officials in the various regions under their authority.[20] Its messengers were capable of delivering missives throughout the empire with great efficiency, with reported travel speeds as fast as almost a hundred miles per day.[21] The barid was not a mail service, and did not normally carry private letters sent by individuals; rather it usually only carried correspondence, such as official reports and decrees, between government agents.[22]

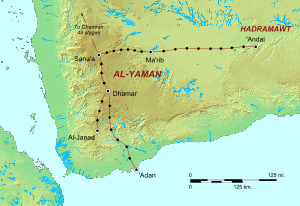

To facilitate the swift delivery of its messages, the barid maintained an extensive network of relay stations, which housed fresh mounts, lodging and other resources for its couriers. The average distance between each barid station was, at least in theory, two to four farsakhs (six to twelve miles);[7][23] according to the 9th-century geographer Ibn Khurradadhbih, there were a total of 930 stations throughout the empire.[13] This relay network was flexible and temporary postal stations could be set up as needed; during military campaigns, for example, new barid stations would be established so that a line of communication could be maintained with the advancing army.[3][24]

Besides carrying correspondence, the barid was sometimes used to transport certain agents of the state, providing a form of fast travel for governors and other officials posted to the provinces.[3][7] The Abbasid caliph al-Hadi (r. 785–786), for example, used the barid service to make the journey from Jurjan to the capital Baghdad after he had received news of his father's death.[25] Use of barid resources was tightly controlled, however, and special authorization was required for other government agents to use their mounts or provisions.[26]

The caliph al-Mansur, on the importance he placed on the barid's surveillance activities.[27]

Surveillance

In addition to its role in as a courier service, the barid operated as an intelligence network within the Islamic state. The postmasters (ashab al-barid) of each district effectively doubled as informants for the central government, and regularly submitted reports to the capital of the state of their respective localities.[28] Any events of significance, such as local trial proceedings,[29] fluctuations in prices of essential commodities,[30] or even unusual weather activity,[31] would be written about and sent to the director of the central diwan, who would summarize the information and present it to the caliph.[32]

Besides the affairs of the provinces in general, barid agents also monitored the conduct of other government officials.[14] Postmasters were to look out for any instances of misconduct or incompetence and inform the caliph of any such behavior. They also reported on the acts and decrees of the local governor and judge, as well as the balance of the treasury.[30] This information enabled the caliph to stay apprised of the performance of his agents, and to dismiss any who had become corrupt or rebellious.[28][33]

See also

- Yam (route) – courier service of the Mongol Empire

- Ulaq (Ottoman Empire) – courier service of the Ottoman Empire

- Furaniq – couriers in general in the medieval Islamic world

- Cursus publicus – courier service of the Roman and Byzantine Empires

Notes

- Frye 1949, p. 585. He takes issue with two of the proposed origins, writing that "Babylonian buridu is just as unsatisfactory as Latin veredus.".

- Paul Horn (1893). Sammlung indogermanischer Wörterbücher. IV. Grundriss der neupersischen Etymologie. Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner. p. 29, last note. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

... Jensen considers αγγαρος to be Babylonian; he explained to me his opinion as follows: berīd = Babyl. buridu (for the older *(p)burādu) = 'courier' and 'fast horse' [English translation of German original text]

- Sourdel 1960, p. 1045.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 5: p. 51 n. 147.

- Goitein 1964, p. 118.

- Glassé 2008, p. 85.

- Silverstein 2006, p. 631.

- M. Rostowzew (1906). Angariae. Beiträge zur alten Geschichte. VI. Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. pp. 249–258, mainly conclusion on p. 249. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Friedrich Preisigke (1907). Die ptolemäische Staatspost [The Ptolemaic state post]. Beiträge zur alten Geschichte. VII. Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. pp. 241–277. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Akkach 2010, p. 15.

- Silverstein 2006, p. 631, argues that Mu'awiyah's and 'Abd al-Malik's barid merely "continued" the pre-existing Byzantine and Sassanid postal systems.

- Hawting 1986, p. 64.

- Ibn Khurradadhbih 1889, p. 153.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 15.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: p. 81.

- Donohue 2003, p. 143.

- Lambton 1968, pp. 266-67.

- Negmatov 1997, p. 80.

- Silverstein 2006, p. 632.

- Silverstein 2006, p. 631-32.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 31: p. 2 n. 8.

- Hodgson 1974, p. 302.

- Yaqut 1959, p. 54 n. 1.

- Goitein 1964, p. 119.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 30: pp. 8-9.

- Goitein 1964, pp. 118-19.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 29: p. 100.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 31: p. 2 n. 5.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: pp. 135-36.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 29: p. 140.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 38: p. 71.

- Qudamah ibn Ja'far 1889, p. 184.

- Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 29: p. 101.

References

- Akkach, Samer (2010). Letters of a Sufi Scholar: The Correspondence of 'Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulusi (1641-1731). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-17102-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donohue, John J. (2003). The Buwayhid Dynasty in Iraq 334 H./945 to 403 H./1012: Shaping Institutions for the Future. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12860-3.

- Frye, Richard N. (October 1949). "Reviews: P.K. Hitti, History of the Arabs". Speculum. 24 (4): 582–587. doi:10.2307/2854655. JSTOR 2854655.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glassé, Cyril (2008). The New Encyclopedia of Islam, Third Edition. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7425-6296-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goitein, S.D. (Apr–Jun 1964). "The Commercial Mail Service in Medieval Islam". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 84 (2): 118–123. doi:10.2307/597098. JSTOR 597098.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawting, G.R. (1986). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hodgson, Marshall G.S. (1974). The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization, Volume 1: The Classical Age of Islam. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-34683-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ibn Khurradadhbih, Abu al-Qasim 'Abd Allah (1889). De Goeje, M.J. (ed.). Kitab al-Masalik wa'l-Mamalik (in Arabic). Leiden: E.J. Brill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). When Baghdad Ruled the Muslim World: The Rise and Fall of Islam's Greatest Dynasty. Cambridge, MA: De Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81480-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambton, A.K.S. (1968). "The Internal Structure of the Saljuq Empire". In Boyle, J.A. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 203–282. ISBN 0-521-06936-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Negmatov, N.N. (1997). "The Samanid state". History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume IV. Delhi: BRILL. pp. 77–94. ISBN 81-208-1595-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Qudamah ibn Ja'far, Abu al-Faraj (1889). De Goeje, M.J. (ed.). Kitab al-Kharadj (Excerpta) (in Arabic). Leiden: E.J. Brill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silverstein, Adam (2006). "Post, or Barid". In Meri, Josef W. (ed.). Medieval Islamic Civilization, An Encyclopedia, Volume 2: L-Z, Index. Leiden and New York: Routledge. pp. 631–632. ISBN 0-415-96692-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sourdel, D. (1960). "Barid". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1045–1046. OCLC 495469456.

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater (ed.). The History of Al-Ṭabarī. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yaqut, Ibn 'Abdallah al-Hamawi (1959). Jwaideh, Wadie (ed.). The Introductory Chapters of Yaqut's Mu'jam al-Buldan. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-08268-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)