Agnoprotein

Agnoprotein is a protein expressed by some members of the polyomavirus family from a gene called the agnogene. Polyomaviruses in which it occurs include two human polyomaviruses associated with disease, BK virus and JC virus, as well as the simian polyomavirus SV40.[2]

| Agnoprotein | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

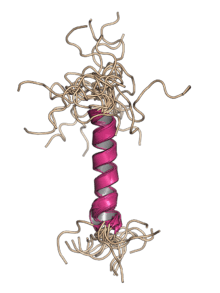

Nuclear magnetic resonance structure of the helix-containing hydrophobic region of the JC virus agnoprotein.[1] | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Polyoma_agno | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01736 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR002643 | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 405 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 2mj2 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Sequence and structure

Agnoprotein is typically quite short: examples from BK virus, JC virus, and SV40 are 62, 71, and 66 amino acid residues long, respectively. Among other known polyomavirus genomes with a predicted agnogene, the length of the resulting predicted protein varies considerably, from as short as 30 to as long as 154 residues.[3] It contains a highly hydrophobic central amino acid sequence, a "bipartite" nuclear localization sequence at the N-terminus, and highly basic amino acids at both termini. Comparison of the sequences of different viral agnoproteins suggests sequence conservation toward the N-terminus with greater variability toward the C-terminus. Formation of amphipathic alpha helices under laboratory conditions has been demonstrated for part of the sequence believed to have a role in mediating dimerization and oligomerization of the protein.[1][2][4] The BK, JC, and SV40 agnoproteins have all been experimentally demonstrated to be phosphorylated in vivo, which appears to improve both protein stability and viral propagation, but no other post-translational modifications have been detected.[2][3]

Expression

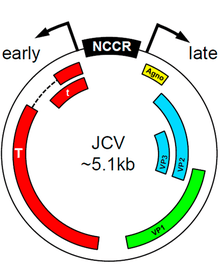

Agnoprotein is expressed from a region of the circular viral genome called the agnogene, an open reading frame contained in a region of the polyomavirus genome that codes for the viral capsid proteins and is known as the "late region" because it is expressed late in the cycle of viral infection and replication.[2] The agnogene and its protein product received their name (from the Greek agnosis, "without knowledge"[3]) because the presence of the open reading frame and corresponding RNA was detected before the existence of the protein product was confirmed.[6]

Cellular localization

Agnoprotein is consistently detected in the cytoplasm of infected cells, with particularly high concentrations in the perinuclear space. It is also detectable in the cell nucleus; in the case of JC virus, nuclear-localized agnoprotein comprises 15–20% of the total agnoprotein expressed.[2]

Function

Agnoprotein is a regulatory protein required for efficient proliferation of the viruses in which it is present, although many polyomaviruses do not have the gene.[4] Its functions are poorly characterized even in well-studied viruses. Null mutant viruses without agnoprotein are generally either incapable of proliferation or are vastly impaired; some such mutants can produce virions, but they may be deficient in exiting the host cell or lack appropriately packaged genetic material.[7][8] Agnoprotein null mutants can successfully proliferate if agnoprotein is present in trans.[7] Although the protein is not found in mature virions, there is some evidence that it can be secreted from infected cells, even before viral exit, and taken up by neighboring uninfected cells.[9]

Agnoprotein has been associated with a number of processes in the viral life cycle, including transcription, replication, and encapsidation of the viral genome.[4] It has also been suggested that agnoprotein functions as a viroporin – that is, a viral protein that alters membrane permeability to facilitate the virus particles' exit from the cell.[10] In addition, effects on the behavior of the host cell itself have been observed, including impaired progression through the cell cycle and deficiencies in DNA repair.[2]

Because it is highly basic, agnoprotein has been suspected to be a DNA-binding protein,[6] but has not been shown to bind DNA.[2] A large number of protein-protein interactions have been reported between agnoprotein and other proteins of both viral and host cell origin. Agnoprotein interacts with the viral proteins small tumor antigen and large tumor antigen as well as with the capsid protein VP1.[2] Host cell proteins reported as binding partners for at least one virus species' agnoprotein include p53, Ku70, PP2A, YB-1, FEZ1, HP1α, α-SNAP, PCNA, and AP-3.[2][3]

In some cases, the agnogene itself has functional significance, even if it cannot express agnoprotein.[2][11] Deletion of the nucleotides in this region has been associated with a variant JC virus capable of infecting cell types not normally targeted by this virus. This variant has been associated with a disease recently described from case reports called JC virus encephalopathy, distinct from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), which has long been associated with JC in immunocompromised individuals.[12][13]

Evolution

Although agnoprotein is critical for proliferation in the polyomaviruses in which it occurs, its distribution among polyomaviruses whose genomes have been sequenced is patchy. It has been well studied in three viruses that infect mammalian hosts, including two human viruses – BK virus and JC virus – and the simian virus SV40; the BK, JC, and SV40 examples are by far the best-studied and have fairly high sequence conservation.[2][3] Additional predicted agnogenes have been identified from the sequenced genomes of other polyomaviruses, and the predicted protein products vary considerably in length and have low sequence identity overall.[3]

The distribution of agnoprotein among polyomaviruses has prompted speculation that there is little evolutionary selection pressure in favor of its presence. Among sequenced BK virus genomes, agnoprotein is the most variable viral protein in amino acid sequence.[3] Differences in tissue tropism and in viral life cycle, particularly in viral exit from the host cell, have also been proposed as explanations for the presence or absence of agnoprotein in various human polyomaviruses.[14]

Avian polyomaviruses

A gene occurs in avian polyomaviruses in a similar genomic position and was originally annotated as an agnogene, but it has no detectable sequence similarity to the mammalian examples. The protein product of this gene has been detected in the capsids of mature virions, leading to its reclassification as VP4 to reflect its distinct role as a structural protein. However, it is still often referred to as "avian agnoprotein 1a".[3][15]

References

- Coric P, Saribas AS, Abou-Gharbia M, Childers W, White MK, Bouaziz S, Safak M (June 2014). "Nuclear magnetic resonance structure revealed that the human polyomavirus JC virus agnoprotein contains an α-helix encompassing the Leu/Ile/Phe-rich domain". Journal of Virology. 88 (12): 6556–75. doi:10.1128/jvi.00146-14. PMC 4054343. PMID 24672035.

- Saribas AS, Coric P, Hamazaspyan A, Davis W, Axman R, White MK, Abou-Gharbia M, Childers W, Condra JH, Bouaziz S, Safak M (October 2016). "Emerging From the Unknown: Structural and Functional Features of Agnoprotein of Polyomaviruses". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 231 (10): 2115–27. doi:10.1002/jcp.25329. PMC 5217748. PMID 26831433.

- Gerits N, Moens U (October 2012). "Agnoprotein of mammalian polyomaviruses". Virology. 432 (2): 316–26. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.024. PMID 22726243.

- Sami Saribas A, Abou-Gharbia M, Childers W, Sariyer IK, White MK, Safak M (August 2013). "Essential roles of Leu/Ile/Phe-rich domain of JC virus agnoprotein in dimer/oligomer formation, protein stability and splicing of viral transcripts". Virology. 443 (1): 161–76. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2013.05.003. PMC 3777628. PMID 23747198.

- Wharton KA, Quigley C, Themeles M, Dunstan RW, Doyle K, Cahir-McFarland E, Wei J, Buko A, Reid CE, Sun C, Carmillo P, Sur G, Carulli JP, Mansfield KG, Westmoreland SV, Staugaitis SM, Fox RJ, Meier W, Goelz SE (18 May 2016). "JC Polyomavirus Abundance and Distribution in Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML) Brain Tissue Implicates Myelin Sheath in Intracerebral Dissemination of Infection". PLOS ONE. 11 (5): e0155897. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1155897W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155897. PMC 4871437. PMID 27191595.

- Jay G, Nomura S, Anderson CW, Khoury G (May 1981). "Identification of the SV40 agnogene product: a DNA binding protein". Nature. 291 (5813): 346–9. Bibcode:1981Natur.291..346J. doi:10.1038/291346a0. PMID 6262654.

- Myhre MR, Olsen GH, Gosert R, Hirsch HH, Rinaldo CH (March 2010). "Clinical polyomavirus BK variants with agnogene deletion are non-functional but rescued by trans-complementation". Virology. 398 (1): 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.029. PMID 20005552.

- Sariyer IK, Saribas AS, White MK, Safak M (May 2011). "Infection by agnoprotein-negative mutants of polyomavirus JC and SV40 results in the release of virions that are mostly deficient in DNA content". Virology Journal. 8 (1): 255. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-8-255. PMC 3127838. PMID 21609431.

- Otlu O, De Simone FI, Otalora YL, Khalili K, Sariyer IK (November 2014). "The agnoprotein of polyomavirus JC is released by infected cells: evidence for its cellular uptake by uninfected neighboring cells". Virology. 468-470: 88–95. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2014.07.054. PMC 4254181. PMID 25151063.

- Suzuki T, Orba Y, Okada Y, Sunden Y, Kimura T, Tanaka S, Nagashima K, Hall WW, Sawa H (March 2010). "The human polyoma JC virus agnoprotein acts as a viroporin". PLoS Pathogens. 6 (3): e1000801. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000801. PMC 2837404. PMID 20300659.

- Khalili K, White MK, Sawa H, Nagashima K, Safak M (July 2005). "The agnoprotein of polyomaviruses: a multifunctional auxiliary protein". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 204 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1002/jcp.20266. PMID 15573377.

- Wüthrich C, Dang X, Westmoreland S, McKay J, Maheshwari A, Anderson MP, Ropper AH, Viscidi RP, Koralnik IJ (June 2009). "Fulminant JC virus encephalopathy with productive infection of cortical pyramidal neurons". Annals of Neurology. 65 (6): 742–8. doi:10.1002/ana.21619. PMC 2865689. PMID 19557867.

- Dang X, Wüthrich C, Gordon J, Sawa H, Koralnik IJ (19 April 2012). "JC virus encephalopathy is associated with a novel agnoprotein-deletion JCV variant". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e35793. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735793D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035793. PMC 3334910. PMID 22536439.

- Van Ghelue M, Khan MT, Ehlers B, Moens U (November 2012). "Genome analysis of the new human polyomaviruses". Reviews in Medical Virology. 22 (6): 354–77. doi:10.1002/rmv.1711. PMID 22461085.

- Johne R, Müller H (April 2001). "Avian polyomavirus agnoprotein 1a is incorporated into the virus particle as a fourth structural protein, VP4". The Journal of General Virology. 82 (Pt 4): 909–18. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-82-4-909. PMID 11257197.